Fuladh ibn Manadhar

Fuladh ibn Manadhar (Persian: دیر فولاد بن مانا), was a Justanid prince, who served as a high-ranking military officer of the Buyid dynasty.

Biography

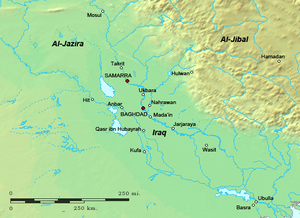

Fuladh was the son of Manadhar, a Justanid king. Fuladh had a brother named Khusrau Shah, who ruled Rudbar after Manadhar. He also had an unnamed sister, who married the Buyid ruler Adud al-Dawla, and bore him two sons, Abu'l-Husain Ahmad and Abu Tahir Firuzshah.[1] During that period, Fuladh, along with a Gilaki officer named Ziyar ibn Shahrakawayh, dominated the Buyid court of Baghdad. After the death of Adud al-Dawla, the Buyid Empire was thrown into civil war; the Empire was disputed between his two sons Samsam al-Dawla and Sharaf al-Dawla. Samsam al-Dawla ruled Iraq, while Sharaf al-Dawla ruled Fars and Kerman.

In 986, a Daylamite officer named Asfar ibn Kurdawayh rebelled against Samsam al-Dawla, and changed his allegiance to Sharaf al-Dawla. However, Asfar quickly changed his mind, and declared allegiance to the latter's other brother Abu Nasr Firuz Kharshadh, who was shortly given the honorific epithet of "Baha' al-Dawla." However, Samsam al-Dawla, with the aid of Fuladh, suppressed the rebellion,[2] and imprisoned Baha al-Dawla. Samsam al-Dawla shortly made peace with Sharaf al-Dawla, and agreed to release Baha al-Dawla. In 987, Sharaf al-Dawla betrayed Samsam al-Dawla, conquered Iraq, and had him imprisoned in a fortress. He then imprisoned Fuladh and had Ziyar executed.[3]

In 988/989, Fuladh was released.[4] After his release, Fuladh then began serving Samsam al-Dawla once again, this time in Shiraz, where he once again became a prominent figure in his court. However, Fuladh later tried to remove the viceroy of Shiraz, which forced him to flee from the wrath of Samsam. Fuladh managed to reach to the court of Fakhr al-Dawla in Ray,[4] where he stayed until death in ca. 994.[5] He had a son named Ibn Fuladh, who would later challenge Buyid authority and claim Qazvin as a part of his own domain.[5]

References

- Donohue 2003, pp. 86-88.

- Kraemer 1992, p. 195.

- Donohue 2003, p. 93.

- Madelung 1992, p. 58.

- Madelung 1975, p. 224.

Sources

- Donohue, John J. (2003). The Buwayhid Dynasty in Iraq 334h., 945 to 403h., 1012: Shaping Institutions for the Future. ISBN 9789004128606. Retrieved 13 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Madelung, W. (1992). Religious and ethnic movements in medieval Islam. ISBN 0860783103. Retrieved 13 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Madelung, W. (1975). "The Minor Dynasties of Northern Iran". In Frye, R. N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 198–249. ISBN 978-0-521-20093-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kraemer, Joel L. (1992). Humanism in the Renaissance of Islam: The Cultural Revival During the Buyid Age. BRILL. pp. 1–329. ISBN 9789004097360.