Frýdlant

Frýdlant, sometimes cited also as Frýdlant v Čechách (Czech pronunciation: [ˈfriːdlant ˈftʃɛxaːx]; German: Friedland in Böhmen) is a town in the Liberec District of the Liberec Region in the Czech Republic.

Frýdlant Frýdlant v Čechách | |

|---|---|

Town | |

View of Frýdlant | |

Coat of arms | |

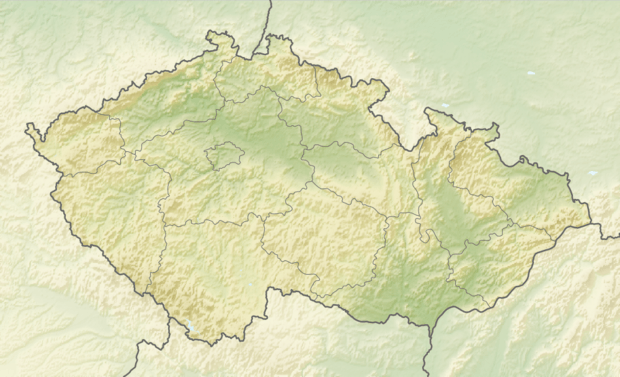

Frýdlant Location in the Czech Republic | |

| Coordinates: 50°55′17″N 15°4′47″E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Liberec |

| District | Liberec |

| Founded | 13th century |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Dan Ramzer |

| Area | |

| • Total | 31.62 km2 (12.21 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 295 m (968 ft) |

| Population (2020-01-01[1]) | |

| • Total | 7,476 |

| • Density | 240/km2 (610/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 464 01 |

| Website | www.mesto-frydlant.cz |

Geography

The town is located in the north of the historic Bohemia region, close to the border with Poland. It is situated in the northern foothills (Frýdlantská pahorkatina) of the Jizera Mountains, on the Smědá river. The population of the town is about 7,500.

There are three areas in the greater Frýdlant area in which most companies are located, with the Czech names[2] followed by German equivalents:

- Albrechtice u Frýdlantu (Olbersdorf) 50°51′35.84″N 15°2′0.09″E

- Frýdlant (Friedland) 50°55′16″N 15°04′49″E

- Větrov (Ringenhain) 50°54′20.59″N 15°4′13.86″E

History

Early history

The area was settled by Slavic (Sorbian) tribes[3] from Lusatia from the 6th century[4] onwards and in the 12th century was incorporated into the Upper Lusatian (Land Budissin) territory, then held by the Margraves of Meissen. It belonged to the Lordship of Seidenberg (Zawidów), which in 1158 passed to the Přemyslid king Vladislaus II of Bohemia.

Frýdlant Castle and the town

In the 13th century the castle was held by the Ronovec family (Ronovci) until the middle of the century when Častolov of Ronov was forced to return the castle and other property to King Ottokar II.[5]

Rulko of Birbstein,[5] also called Rudolf of Bieberstein,[4] purchased the castle and surrounding land from the king in 1278.[5][6] The castle is situated near the center of town, above the Smědá river.[7] Rulko held property in Silesia and Upper Lusatia and family members held court positions.[5]

There were important trade routes through the area, including to Görlitz and to Lusatia.[5] From Görlitz, Via Regia provided routes to Russia, Spain, and throughout Europe.[8] Perhaps as early as 1304, but by 1381, a moat and curtain walls were constructed to surround and protect the town, which were largely removed in 1774.[9]

The Birbsteins (Biebersteins) supported King Sigmund during the Hussite Wars (1419–1434). Frýdlant was apprehended by the Hussites in 1428.[5] Between 1428 and 1433, the town was raided several times.[4] Frydlant castle and town, also called Frydlant Manor went to Emperor Ferdinand I when Christopher, the last of the line of the Birbsteins, died in 1551.[5] The castle went into the Redern family when Bedřich bought it in 1558. Since the ruler set the religion for an area at that time, Bedřich made Protestant churches and closed the Catholic church in Hejnice that had been the destination for religious pilgrimages. Several new villages were established and the production of linen cloth resulted in an economic boom during the initial years of the Redern family.[5] Marco Spazzio di Lancio, an Italian architect hired by the family, expanded the castle in the 16th century.[10]

Christoph von Redern was considered a traitor when he opposed Emperor Ferdinand II and supported Frederick V of the Palatinate (also known as Fridrich Falcký) after the Battle of White Mountain in 1620. All of his property was then taken from him.[5] Frýdlant then went to Albrecht von Wallenstein, who became Duke of Frýdlant and lived at Jičín.[6][10] Wallenstein returned Catholicism to the area and held the lands until 1634, when he was assassinated.[5] Frýdlant then went to Matthias Gallas of Campo as a reward for his fight against Wallenstein in 1636 by Emperor Ferdinand II.[5]

At the end of the Thirty Years' War, the castle was possessed by the Swedes. They constructed fortified barbicans and strengthened the defensive walls.[10] In 1639, Christoph von Redern returned to Frydlant after a period of exile. One year later, the Swedes left Bohemia entirely.[11] Due to the loss of religious freedom and Protestants being forced to adopt the Catholic religion, many exiles did not return to the area.[5][11] The area continued to suffer through 1642.[5]

The estates remained with Matthias Gallas and the Gallas line until 1757. When Earl Philip Joseph Galas died without children, the estate went to Christian Philip Clam, his nephew, under the stipulation that going forward the family would assume the Gallas coat-of-arms and the family surname would be changed to Clam-Gallas.[5]

In 1800[12] or 1801,[7] the Clam-Gallas family opened the castle to the public as a museum.[7][12] Napoleon and his troops were in the town in 1813, to the detriment of the citizens of the town. A textile industry developed in the town in the 19th century.[4] In 1899, the Plague Column was constructed in the memory of the victims of five plague epidemics. The town also survived several significant fires.[4]

Until 1918, Friedland in Böhmen was part of the Austrian monarchy (Cisleithanian side after the Compromise of 1867). It was the head of a district with the same name, one of the 94 Bezirkshauptmannschaften in the Bohemian crown land.[13] It remained with the Clam-Gallas family until the last descendant Clotilda, who died in 1982, having moved to Vienna in April 1945.[5]

Now, the building complex consists of the Gothic castle with a high tower and a Renaissance château. Today it is one of the most visited sites in the Czech Republic.[12] There are exhibits, such as of Albrecht von Wallenstein, the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), and an armoury of 1,000 weapons used for military and hunting. The castle includes the St Ann's Chapel, the Knights' Hall, rooms for the count and countess, and a working kitchen. [12]

Church of the Holy Cross

The Church of the Holy Cross was built in the mid-16th century by Italian architects,[10] which has a mixture of architectural styles due to construction over the years. A Renaissance style chapel for the Redern family tomb was built in 1566.[4] A mausoleum was built for the Redern family in 1610.[10]

Railway

In 1875, a railway line from Liberec via Frýdlant to Zawidów was put into operation. Lines to Mirsk (Friedberg) and the Frýdlant–Heřmanice Railway to Zittau followed soon.

Town Hall and Museum

In 1893, a new town hall was erected in the center of the town at Masaryk Square according to plans by Franz Neumann, a Viennese architect. Inside the town hall is a bust of Albrecht von Wallenstein, created by a sculptor from nearby Raspenava. The building has stained glass windows and the exterior has statues of Self-Sacrifice and Justice. Now, the town museum, Frýdlant City Museum, is located on the second floor with archaeological and historical exhibits.[14][15]

Nazi Germany

Following the 1938 Munich Agreement, the town was occupied by Nazi Germany and incorporated as Friedland (Isergebirge), one of the municipalities in the Reichsgau Sudetenland.[16] After World War II, it fell back to the Third Czechoslovak Republic and renamed Frýdlant v Čechách. The German-speaking population was expelled according to the Beneš decrees and replaced by Czech settlers.

In 2016, Georg Mederer and Erich Stenz, German treasure hunters, claimed that trucks delivered items from the amber chamber of Saint Petersburg, Russia to the castle in the late period of the war. They state that the items previously owned by Peter the Great were stolen by the Nazis and stored in the castle cellars with contemporaneously constructed brick walls. The men further state that they have been unable to search for the stolen items due to the Czech government and the Czech National Heritage Institute.[17][18] There is also a theory that the amber room, including decorative wall panels, were shipped to Konigsberg, now Kaliningrad, and the contents were destroyed during bombing of the town.[18]

In popular culture

The town's castle is believed to be the source of inspiration for The Castle (1926) by Franz Kafka.[10][7]

Notable people

- Alexander Bittner (1850–1902), paleontologist and geologist

- Josef Blösche (1912–1969), SS soldier

- Jan Budař (born 1977), actor, director and musician

- Jan Rajnoch (born 1981), footballer

- Tomáš Plíhal (born 1983), ice hockey player

- Karolína Bednářová (born 1986), volleyball player

- Ladislav Šmíd (born 1986), ice hockey player

- Antonín Hájek (born 1987), ski jumper

Twin towns – sister cities

Frýdlant is twinned with other towns sharing the historic German name Friedland:[19]

References

- "Population of Municipalities – 1 January 2020". Czech Statistical Office. 2020-04-30.

- "Frýdlant, obec v okrese Liberec - všechny části obce (Frýdlant, village in the Liberec district - all parts of the village)". regiony.kurzy.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 25 May 2017 – via Google translate.

- "Sorbs, Upper Lusatia.Cultural". Ober Lausitz. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- "Historie". www.mesto-frydlant.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 26 May 2017 – via translate.google.com.

- "Frýdlant Manor". Lázně Libverda. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- "Frýdlant". Cesky raj, Bohemian Paradise Association. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- Rob Humphreys; Susie Lunt (2002). Czech and Slovak Republics. Rough Guides. p. 280. ISBN 978-1-85828-904-5.

- "The Via Regia – The royal road". Ober Lausitz. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- "The Frýdlant town curtain walls". Cesky raj, Bohemian Paradise Association. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- DK Publishing (2 May 2011). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Czech and Slovak Republics: Czech and Slovak Republics. DK Publishing. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-7566-8375-7.

- Between Lipany and White Mountain: Essays in Late Medieval and Early Modern Bohemian History in Modern Czech Scholarship. BRILL. 18 July 2014. pp. 323–324. ISBN 978-90-04-27758-8.

- "Frýdlant Castle and Chateau". Cesky raj, Bohemian Paradise Association. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- Wilhelm Klein (1967). Die postalischen Abstempelungen und andere Entwertungsarten auf den österreichischen Postwertzeichen-Ausgaben 1867, 1883 und 1890. Geitner; Auslieferung: Wien, Briefmarken-Kolbe.

- "Neo-Renaissance style Town Hall, Frýdlant". Cesky raj, Bohemian Paradise Association. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- "Frýdlant City Museum". Cesky raj, Bohemian Paradise Association. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- "Reichsgau Sudetenland". verwaltungsgeschichte.de (in German). Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- Chris Johnstone (2 November 2016). "German Treasure Hunters Claim Russian Treasure Hidden in Czech Castle". Radio Prague. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- Ian Harvey (20 March 2016). "German treasure hunters believe they found Amber Room wall panels". The Vintage News. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- "Partnerská města" (in Czech). Město Frýdlant. Retrieved 2019-08-25.