FreeCell

FreeCell is a solitaire card game played using the standard 52-card deck. It is fundamentally different from most solitaire games in that very few deals are unsolvable,[1] and all cards are dealt face-up from the very beginning of the game.[2] Although software implementations vary, most versions label the hands with a number (derived from the seed value used by the random number generator to shuffle the cards).[2]

| A patience game | |

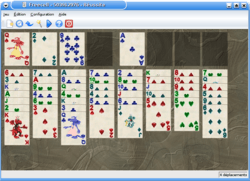

A game of Freecell on KDE | |

| Named variants | Baker's Game |

|---|---|

| Family | Freecell |

| Deck | Single 52-card |

| See also Glossary of patience terms | |

Microsoft has included a FreeCell computer game with every release of the Windows operating system since 1995, greatly contributing to the game's popularity. It is so definitive for many FreeCell players that many other software implementations strive for compatibility with its random number generator in order to replicate its numbered hands.[2][3]

Rules

Construction and layout

- One standard 52-card deck is used.

- There are four open cells and four open foundations. Some alternate rules use between one and ten cells.

- Cards are dealt face-up into eight cascades, four of which comprise seven cards each and four of which comprise six cards each. Some alternate rules will use between four and ten cascades.

Building during play

- The top card of each cascade begins a tableau.

- Tableaux must be built down by alternating colors.

- Foundations are built up by suit.

Moves

- Any cell card or top card of any cascade may be moved to build on a tableau, or moved to an empty cell, an empty cascade, or its foundation.

- Complete or partial tableaus may be moved to build on existing tableaus, or moved to empty cascades, by recursively placing and removing cards through intermediate locations. Computer implementations often show this motion, but players using physical decks typically move the tableau at once.

The number of cards a player can move is equivalent to number of empty cells plus one, with that number doubling based on how many empty cascades there are. The mathematical equation for the number of cards that can be moved is (2M)×(N + 1), where M is the number of empty cascades and N is the number of empty cells.[4]

Victory

- The game is won after all cards are moved to their foundation piles.

It is estimated that 99.999% of possible deals are solvable. Deal number 11982 from the Windows version of FreeCell is an example of an unsolvable FreeCell deal, the only deal among the original "Microsoft 32,000" which is unsolvable.[2]

History

One of the oldest ancestors of FreeCell is Eight Off. In the June 1968 edition of Scientific American, Martin Gardner described in his "Mathematical Games" column a game by C. L. Baker that is similar to FreeCell, except that cards on the tableau are built by suit rather than by alternate colors. Gardner wrote, "The game was taught to Baker by his father, who in turn learned it from an Englishman during the 1920s."[5] This variant is now called Baker's Game. FreeCell's origins may date back even further to 1945 and a Scandinavian game called Napoleon in St. Helena (not the game Napoleon at St. Helena, also known as Forty Thieves).[2]

Paul Alfille changed Baker's Game by making cards build according to alternate colors, thus creating FreeCell. He implemented the first computerised version of it in the TUTOR programming language for the PLATO educational computer system in 1978. Alfille was able to display easily recognizable graphical images of playing cards on the 512 × 512 monochrome display on the PLATO systems.[6]

This original FreeCell environment allowed games with 4–10 columns and 1–10 cells in addition to the standard 8 × 4 game. For each variant, the program stored a ranked list of the players with the longest winning streaks. There was also a tournament system that allowed people to compete to win difficult hand-picked deals. Paul Alfille described this early FreeCell environment in more detail in an interview from 2000.[7]

In 2012, researchers used evolutionary computation methods to create winning FreeCell players.[8]

Solver complexity

The FreeCell game has a constant number of cards. This implies that in constant time, a person or computer could list all of the possible moves from a given start configuration and discover a winning set of moves or, assuming the game cannot be solved, the lack thereof. To perform an interesting complexity analysis one must construct a generalized version of the FreeCell game with 4 × n cards. This generalized version of the game is NP-complete;[9] it is unlikely that any algorithm more efficient than a brute-force search exists that can find solutions for arbitrary generalized FreeCell configurations.

There are 52! (i.e., 52 factorial), or approximately 8×1067, distinct deals. However, some games are effectively identical to others because suits assigned to cards are arbitrary or columns can be swapped. After taking these factors into account, there are approximately 1.75×1064 distinct games.[2]

References

- Leonhard, Woody (2009). Windows 7 All-in-One for Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 293. ISBN 9780470487631.

- Keller, Michael (August 4, 2015). "FreeCell -- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)". Solitaire Laboratory. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- "PySol - Rules for Freecell". PySolFC documentation. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "solitaire - FreeCell: How many cards can be moved at once?". Board & Card Games Stack Exchange.

- Gardner, Martin (June 1968). "Mathematical Games". Scientific American. 218 (6): 114. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0668-112.

- Kaye, Ellen (October 17, 2002). "One Down, 31,999 to Go: Surrendering to a Solitary Obsession". New York Times.

- Cronin, Dennis (May 4, 2000). "Interview with Paul Alfille". Freecell.net. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- Elyasaf, Achiya; Hauptman, Ami; Sipper, Moshe (December 2012). "Evolutionary Design of FreeCell Solvers" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Computational Intelligence and AI in Games. 4 (4): 270–281. doi:10.1109/TCIAIG.2012.2210423.

- Helmert, Malte (March 2003). "Complexity results for standard benchmark domains in planning". Artificial Intelligence. 143 (2): 219–262. doi:10.1016/S0004-3702(02)00364-8.

Additional sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to FreeCell. |

- "OHSU scientists say FreeCell can be adapted to spot early signs of dementia". Oregon Health & Science University. Retrieved June 1, 2017.

- O'Hale, Marty M. (August 14, 2007). "The Four Virtues of FreeCell". The Escapist Magazine. Retrieved June 9, 2012.