Frederick Bakewell

Frederick Collier Bakewell (29 September 1800 – 26 September 1869) was an English physicist who improved on the concept of the facsimile machine introduced by Alexander Bain in 1842 and demonstrated a working laboratory version at the 1851 World's Fair in London.

Frederick Collier Bakewell | |

|---|---|

| Born | 29 September 1800 Wakefield, West Yorkshire, England |

| Died | 26 September 1869 (aged 68) |

| Citizenship | British |

Biography

Born in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, he eventually moved to Hampstead, Middlesex where he lived until his death. Bakewell was married to Henrietta Darbyshire with whom he had two sons, Robert and Armitage.[1]

Image telegraph

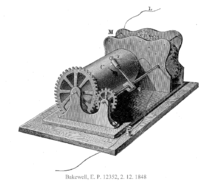

Bakewell's "image telegraph" had many of the features of modern facsimile machines, and replaced the pendulums of Bain's system with synchronized rotating cylinders.

The system involved writing or drawing on a piece of metal foil with a special insulating ink; the foil was then wrapped around a cylinder which slowly rotated, driven by a clock mechanism. A metal stylus driven by a screw thread traveled across the surface of the cylinder as it turned, tracing out a path over the foil. Each time the stylus crossed the insulating ink, the current through the foil to the stylus was interrupted. At the receiver, a similar pendulum-driven stylus marked chemically treated paper with an electric current as the receiving cylinder rotated.

The chief problems with Bakewell's machine were how to keep the two cylinders synchronized and to make sure that the transmitting and receiving styli started at the same point on the cylinder at the same time. Despite these problems, Bakewell's machine was capable of transmitting handwriting and simple line drawings along telegraph wires. The system, however, never became commercial. Later, in 1861, the system was improved by an Italian priest, Giovanni Caselli who was able to use it to send handwritten messages as well as photographs on his pantelegraph. He introduced the first commercial telefax service between Paris and Lyon eleven years before the invention of workable telephones.[2][3]

Other work

In addition to his work on facsimile transmission, he held patents for many other innovations. Bakewell also wrote texts on physics and natural phenomena.

Books

- Philosophical conversations – 1833

- Electric science; its history, phenomena, and applications – 1853

Footnotes

References

- Birth / Death Dates

- A widely cited online biography

- Chronological Index of Patents Applied for and Patents Granted for the Year 1863 – Bennet Woodcroft – 1864