Fred Guardineer

Frederick B. Guardineer (October 3, 1913 – September 13, 2002)[2] was an American illustrator and comic book writer-artist best known for his work in the 1930s and 1940s during what historians and fans call the Golden Age of Comic Books, and for his 1950s art on the Western comic-book series The Durango Kid.

| Fred Guardineer | |

|---|---|

| Born | Frederick B. Guardineer October 3, 1913 Albany, New York |

| Died | September 13, 2002 (aged 88) |

| Nationality | American |

| Area(s) | Writer, Artist |

| Pseudonym(s) | F.B.G.[1] Gene Baxter[1] Lance Blackwood[1] |

| Awards | Inkpot Award, 1988 |

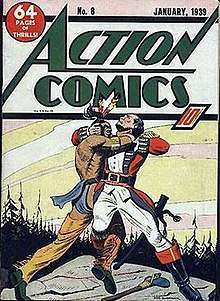

A pioneer of the medium itself, Guardineer contributed two features to the seminal Action Comics #1, the comic book that introduced Superman.

Biography

Early life and career

Fred Guardineer was born in Albany, New York.[3] He acquired a fine arts degree in 1935, then moved to New York City, where he drew for pulp magazines.[3] The following year he joined the studio of the quirkily named Harry "A" Chesler, an early "packager" supplying comics features on demand for publishers entering the emerging medium of comic books. There he drew adventure features such as "Dave Dean" and the science-fiction feature "Dan Hastings" before going freelance in 1938.[3]

Guardineer's first known comics credits appear in several one- to three-page Western and comic-Western stories, and in spot illustrations for a text story, in Centaur Publications' Star Ranger #2 (cover-dated April 1937). Through that year, he continued writing and drawing such short features in a variety of genres in some of the medium's first comics, including Centaur's Star Comics, '"Funny Pages and Funny Picture Stories.[4]

He is among the contributors to the future DC Comics' landmark title Action Comics #1 (June 1938), the comic that introduced Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster's seminal superhero Superman. There Guardineer wrote, drew and lettered the 12-page feature introducing his magician-hero creation Zatara, a character remaining in the DC stable as of the 21st century. Guardineer was also one of the artists on two features handled previously by Creig Flessel in More Fun Comics: "Pep Morgan" (on which he sometimes used the pseudonym Gene Baxter) and, in Detective Comics, "Speed Saunders, Ace Investigator".[4]

He married Ruth Ball in 1938 and bought a home in Long Island, New York the following year.[5]

Guardineer's other early work includes art for Quality Comics, where he created the character Blue Tracer; and Columbia Comics, where he worked with former DC editor Vin Sullivan, who had edited Action Comics.[4]

Later life and career

Guardineer followed Sullivan to the editor's next venture, the comic-book company Magazine Enterprises, which Sullivan founded. There from 1949–1955, Guardineer drew writer Gardner Fox's Old West masked-crimefighter series The Durango Kid. In the late 1940s, he also drew for such Lev Gleason Publications comics as Black Diamond Western and Crime Does Not Pay.[4] In 1955, Guardineer retired from comics and worked 20 years with the U.S. Postal Service,[3][5] and during this time did wildlife illustrations for publications including The Long Island Fisherman.[5] He was a member of the Outdoor Writers Association of America.[5]

Popular-culture historian Ron Goulart called Guardineer

...a true nonpareil, an artist whose style was unmistakably his own. ... His style was almost fully formed from the start. He seems always to have thought in terms of the entire page, never the individual panel. Each of his pages is a thoughtfully designed whole, giving the impression sometimes that Guardineer is arranging a series of similar snapshots into an attractive overall pattern, a personal design that will both tell the story clearly and be pleasing to the eye....[6]

Comics historian Mark Evanier wrote that during Guardineer's years away from comics, Mad magazine writer and editor Jerry DeFuccio located him "and became the first of many collectors to pay what Guardineer considered tidy sums to re-create some of his old covers."[7] Guardineer again lost contact with the comics community until 1998, when a comics fan found him in northern California and convinced him to attend that year's Comic-Con International in San Diego, California. There, he was part of an Evanier-hosted panel "of every surviving person who'd had a hand in the creation of the historic Action Comics #1. [When presented with the convention's Inkpot Award,] Fred was confined to a wheelchair ... but with great effort, he insisted on standing as he made a brief but eloquent acceptance speech."[7] Guardineer later was a guest at WonderCon, in Oakland, California.[7]

One source says Guardineer moved to San Ramon, California, where he died in 2002,[3] though the Social Security Death Index gives his last place of residence as Babylon, New York (ZIP Code 11702) in Suffolk County, Long Island.[2]

Awards

- 1998 Inkpot Award.

References

- Bails, Jerry; Ware, Hames, eds. "Guardineer, Fred". Who's Who of American Comic Books, 1928–1999. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2014.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Frederick B. Guardineer, Social Security Number 111-12-8578, at the United States Social Security Death Index. Retrieved on January 8, 2016| Archived from the original on January 8, 2016.

- Fred Guardineer at the Lambiek Comiclopedia

- Fred Guardineer at the Grand Comics Database

- Black, Bill (September 2001). "Fred Guardineer: The M.E. Years". Alter Ego. Vol. 3 no. 10. p. 15.

- Goulart, Ron (1986). The Great Comic Book Artists. New York City: St. Martin's Press. p. page #?.

- Evanier, Mark (May 6, 2004). "Fred Guardineer, R.I.P." News From ME (column). Retrieved October 9, 2011.

Further reading

- Outdoors Unlimited (April 1987), Outdoor Writers Association of America