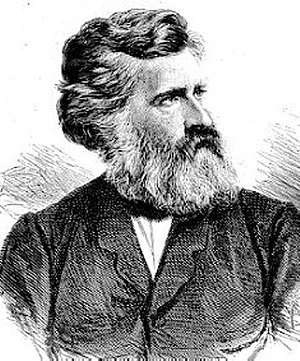

Franz Duncker

Franz Duncker (4 June 1822 – 18 June 1888) was a German publisher, left-liberal politician[1] and social reformer.[2]

Franz Duncker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Franz Gustav Duncker 4 June 1822 |

| Died | 18 June 1888 Berlin, Germany |

| Occupation | Publisher Politician |

| Spouse(s) | Karoline Wilhelmine "Lina" Tendering (1828–1885) |

| Children | Marie Duncker / Magnus (1856–) |

Life

Family provenance and early years

Franz Gustav Duncker was one of the sons of the publisher Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Duncker. His brothers included the publisher Alexander Duncker, the historian Maximilian Wolfgang Duncker and the Berlin mayor, Hermann Duncker.[3] Duncker studied Philosophy and History at Berlin.[2] During this time he joined the "Alt Berliner" student fraternity and in 1842 another student fraternity, the "Leseverein". After this he returned to the family publishing business.[2]

In 1848 he served as a captain ("Hauptmann") in the Berlin Citizen Militia ("Bürgerwehr").[2] The next year, 1849, he married Karoline Wilhelmine "Lina" Tendering (1828–1885),[4] the granddaughter of a bishop who as "Lina Duncker" would create one of several fashionable political and literary salons in Berlin.[5] A frequent guest was Gottfried Keller who fell in love with Lina's sister Betty Tendering, and later featured her, renamed as Dorothea Schönfund, in his semi-autobiographical novel, "Grüne Heinrich".

Franz and Lina Duncker's marriage would also give rise to one recorded child, their daughter Marie, born in 1856.[5]

The publisher

In 1850 Duncker acquired Wilhelm Besser's "Bessersche Verlags Buchhandlung" publishing business, and in 1853 he acquired from Aaron Bernstein the Urwähler-Zeitung, a pro-democracy daily newspaper. The world of newspapers was a rapidly evolving one. The Urwähler-Zeitung had been founded only in 1849, and in March 1853 it was banned. Duncker relaunched as a liberal (opposition) voice with a new name as the Berliner Volks-Zeitung.[5] As the Berliner Volks-Zeitung the paper continued to be published for nearly a century. By the 1860s circulation had risen to roughly 22,000, making it the number one newspaper in the Prussian capital.[1] The business acquired from Besser also continued to thrive as a book publisher. Works by political philosophers published by Duncker included:

- Die Philosophie Herakleitos des Dunklen von Ephesos by Ferdinand Lassalle (1858)

- Der italienische Krieg und die Aufgabe Preußens by Ferdinand Lassalle (1859)

- Zur Kritik der Politischen Oekonomie by Karl Marx[6]

- Po und Rhein, an anonymously published "pamphlet", actually by Friedrich Engels (1858)[7]

Control of the publishing business was taken over in 1877 by a man called Wilhelm Hertz.[8] Duncker sold the Berliner Volks-Zeitung to Emil Cohn in 1885: twenty years later, in 1904, it was acquired by Rudolf Mosse.

The political activist

Thwarted revolution in 1848 was followed by political repression in Prussia, but the ideas of liberalism and nationalism that had underpinned 1848 never completely disappeared, and Duncker was supportive of both aspirations. In 1858 he was one of the founders of the German National Association, serving on its principal committees till 1867. He was also, in 1861, a founder of the liberal-leaning Progressive Party,[5] serving on its national election committee. He joined the Progressive Party executive committee in 1874.

Between 1861 and 1877 Duncker sat as a Progressive Party member in the Prussian House of Representatives, representing the Saarbrücken-Ottweiler electoral district initially and, from 1867, the Berlin 4th electoral district.[2] In 1863 he was a member of the "Committee of 36" that convened in Frankfurt am Main in the context of concern on the part of liberals that the German Confederation was increasingly dominated by its two largest member-states, Prussia and Austria, neither of which was seen as a natural ally in the search for a liberal-nationalist future that preoccupied progressive thinkers at the time.[9]

During the 1861 Constitutional Conflict he was strongly opposed to militia (Landwehr) reforms because he feared they would lead to a weakening of citizen spirit which till that time had been a unique corrective against resurgent militarism.[1] In the Prussian Assembly he also, in 1873, condemned government tactics in what came to be known as the German Kulturkampf, arguing that demonising those opposed to the government position carried echoes of the way the authorities had persecuted democratic proponents after 1848.[10]

Along with his membership of the Prussian House of Representatives, between 1867 and 1878 Duncker also belonged to the national legislature, the Confederation Reichstag and its 1871 successor, the Imperial Reichstag, sitting as a Progressive Party member and representing an electoral district that included the Berlin quarters Spandau and Friedrich-Wilhelm-Stadt.[2]

In 1865 Duncker became chairman of the Greater Berlin Artisans' League ("Handwerkerverein").[11] Together with Max Hirsch and Franz Hermann Schulze-Delitzsch he established the Hirsch-Dunckersche Gewerkvereine, which was a form of liberal trades union movement, founded in 1868.[11][12]

References

- Hans-Ulrich Wehler, Deutsche Gesellschaftsgeschichte: Von der "Deutschen Doppelrevolution" bis zum Beginn des Ersten Weltkrieges, 1849–1914. (= Deutsche Gesellschaftsgeschichte. Vol 3). C. H. Beck, 1995, ISBN 3-406-32263-8, p. 162, 259, 438.

- "Duncker, Franz Gust". Deutscher Parlaments-Almanach (Reichstagsprotokolle – Verhandlungen des Deutschen Reichstags und seiner Vorläufer). Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, München. 13 February 1877. pp. 145–146. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- Wolfgang Zorn (1959). "Duncker, Karl Friedrich Wilhelm: Verleger, * 25.3.1781 Berlin, † 15.7.1869 Berlin. (evangelisch)". Neue Deutsche Biographie. p. 195. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ""Bedeutende Frauen aus Voerde"- Lina Tendering". Nachrichten aus Dinslaken, Hünxe und Voerde. FUNKE MEDIEN NRW GmbH ("WAZ"), Essen. 7 March 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- Petra Wilhelmy (1989). Register der Salonnièren ... Duncker, Lina. Der Berliner Salon im 19. Jahrhundert (1780–1914). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin & New York. p. 642. ISBN 3-11-011891-2.

- Karl Marx. "Zur Kritik der Politischen Ökonomie". Lüko Willms, Frankfurt am Main i.A. Gesamtverzeichnis "MLWerke". Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- Friedrich Engels (4 August 1998). "Po und Rhein". Lüko Willms, Frankfurt am Main i.A. Gesamtverzeichnis "MLWerke". Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- Theodor Fontane, Martha Fontane: Ein Familienbriefnetz, Band 4 von Schriften der Theodor Fontane Gesellschaft, Brief 142, Nummer 265, Herausgeberin Regina Dieterle, Verlag Walter de Gruyter, 2002, ISBN 9783110857825

- Richard Schwemer (1918). ""Geschichte der freien Stadt Frankfurt a. M. (1814–1866)"". Joseph Baer & Cie & Internet Archive. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- Wilhelm Ribhegge: Preußen im Westen. Kampf um den Parlamentarismus in Rheinland und Westfalen. Münster 2008 (Sonderausgabe für die Landeszentrale für politische Bildung NRW) p. 223.

- Todd H. Weir (2014). Politics and Free Religion in the 1860s and 1870s - Left-liberalism. Secularism and Religion in Nineteenth-Century Germany: The Rise of the fourth confession. CUP. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-107-04156-1.

- Joan Campbell (1992). European Labor Unions - Germany to 1945. European Labor Unions. Greenwood Press, Westport (Conn.). p. 155. ISBN 0-313-26371-X.