Frankliniella tritici

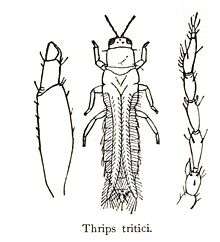

Frankliniella tritici, the eastern flower thrips, is a species of thrips (Order Thysanoptera) in the genus Frankliniella.[2] F. tritici inhabits blossom, such as dandelion flowers.[3] They can directly damage plants, grasses and trees, in addition to commercial crops,[3] and as a vector for tospoviruses, a form of plant virus, it particularly affects small fruit production in the United States, including strawberries, grapes, blueberries and blackberries.[2] It can also affect alfalfa, oats, beans and asparagus crops.[4] The species features strap-like wings edged with long hairs, a design which increases aerodynamic efficiency in very small arthropods; the reduced drag means the insect uses less energy.[3] They extract nutrients directly from individual plant cells, and may also digest cells of fungi in the leaf litter.[3]

| Frankliniella tritici | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | Frankliniella |

| Species: | F. tritici |

| Binomial name | |

| Frankliniella tritici (Fitch, 1855) [1] | |

The genus Frankliniella has 40 species, of which several others are pests - including Frankliniella occidentalis (Western flower thrips), Frankliniella vaccinii (blueberry thrips) and Frankliniella fusca (tobacco thrips).[5]

The 'eastern' part of its common name is due to its common occurrence to the east of the Rocky Mountains, whereas the habitat of western flower thrips extends through the entire United States and Canada.[2]

It is challenging to distinguish the various species of thrips, without resorting to microscopic examination.[2]

F. tritici can be subject to parasitism by the Thripinema fuscum nematode.[6]

Frankliniella tritici subsp. bispinosa

This subspecies is approximately 0.25 inches (6.4 mm) in length, and is an orange and yellow colour.[7]

It attacks the stamen and young berries of strawberry blossoms in springtime.[7] They extract sap from the fruit and their flowers, which can cause the fruits growth to be stunted, and also leads to discolouration.[8]

They are a migrant species; in springtime, they travel long distances from the South, into the Northeast and Midwest parts of America, borne on high-altitude wind currents.[8]

References

- "Species Frankliniella tritici (Fitch, 1855)". Thrips of the World Checklist. Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- John L. Capinera (2008). Encyclopedia of Entomology. 1 (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1.

- Peggy Macnamara & James H. Boone (2005). Illinois insects and spiders. University of Chicago Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-226-50100-0.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Dennis S. Hill (1987), Agricultural insect pests of temperate regions and their control, CUP Archive, p. 253, ISBN 978-0-521-24013-0

- Ross H. Arnett (2000). American insects: a handbook of the insects of America north of Mexico (2nd ed.). CRC Press. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-8493-0212-1.

- Parwinder S. Grewal; Ralf-Udo Ehlers; David I. Shapiro-Ilan (2005), Nematodes as biocontrol agents, CABI Publishing, p. 404, ISBN 9781845931421

- University of Florida Agricultural Experiment Station (1926), Bulletin - University of Florida, Agricultural Experiment Stations, University of Florida, p. 515

- John Andrew Eastman (2003). The book of field and roadside: open-country weeds, trees, and wildflowers of eastern North America. Stackpole Books. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-8117-2625-2.