Francisco de Cuellar

Francisco de Cuéllar was a Spanish sea captain who sailed with the Spanish Armada in 1588 and was wrecked on the coast of Ireland. He gave a remarkable account of his experiences in the fleet and on the run in Ireland.[1]

Captain Francisco de Cuéllar | |

|---|---|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1562 Valladolid, Spain |

| Died | After 1606 |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Spanish Navy |

| Years of service | 1581-1606 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | War of the Portuguese Succession Anglo-Spanish War • Spanish Armada |

Life before the Spanish Armada

Cuéllar's place and date of birth are uncertain, but undoubtedly he was of Castilian origin. The surname refers to a village in the province of Segovia called Cuéllar, and is a common Castilian family name. According to recent research ("El capitán Francisco de Cuéllar antes y después de la jornada de Inglaterra", by Rafael M. Girón Pascual), there was a captain named Francisco de Cuéllar, perhaps our man, born in the city of Valladolid, who was baptized on March, twelve, 1562 in the parish of San Miguel.

Cuéllar was a member of the army that conquered Portugal in 1581. Following Rafael Giron, he served in the Diego Flores Valdés navy, which sailed to the Strait of Magellan, aboard the frigate Santa Catalina. He was later in Paraiba, Brazil, where he participated in expelling French settlers from the area. After that he served under the Marquis of Santa Cruz in the Azores islands.

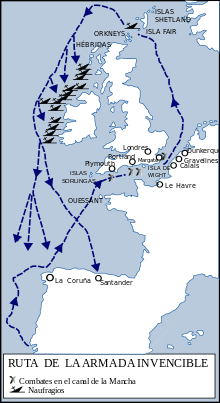

Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada in Ireland suffered heavy losses during an extraordinary season of storms in the autumn of 1588. Cuéllar had been captain of the San Pedro a galleon of the squadron of Castille, one of the front line squadrons of the Spanish Armada, when the ship broke the Armada formation in the North Sea. He was accused of disobedience and was sentenced to death by hanging by the Major General of the fleet, Francisco Arias de Bobadilla. Cuéllar was sent to the galleon, San Juan de Sicilia, for execution of sentence by the Auditor General, Martin de Aranda.

Sentence was not executed, and Cuéllar remained on board until the galleon, a member of the Levant squadron, which suffered heavy losses on the return voyage (less than 400 survivors returned out of 4,000 who set sail), anchored in the company of two others on the Irish coast, a mile off Streedagh Strand in modern County Sligo. On the fifth day at anchor all three ships were driven onto the beach, where they broke up. Of the 1,000 men on board, 300 survived.

Local inhabitants beat, robbed and stripped those who came ashore. But Cuéllar, having clung to a loose hatch, floated to shore unobserved and concealed himself among rushes. He was in poor shape, and was joined by a naked fellow survivor who was dumbstruck and soon died. Cuéllar kept drifting in and out of consciousness; at one point he and his fellow survivor were discovered by two armed men, who covered them with rushes before going to the shore to loot. At another point he saw 200 horsemen riding across the beach.

When Cuéllar crawled out he saw 800 corpses littering the sand, with ravens and wild dogs feeding on them. He moved on to the Abbey of Staad, a small church which had been torched by the English after its friars had fled. He saw twelve of his countrymen hanging from nooses tied to iron bars of the windows within the church ruins. A local woman who was driving cattle into hiding in the woods warned him to stay out of the road, and he then met two naked Spanish soldiers, who informed him that English soldiers had killed 100 captive survivors.

The Spaniards saw 400 corpses on another beach. When they stopped to bury the bodies of two officers they were confronted by four locals who demanded the remainder of de Cuellar's clothes. Another local ordered them to leave him alone and directed the Spaniards to his own village. They made their way there barefoot in cold weather, through a wood where they met two young men travelling with an old man and a young woman: the young men attacked de Cuéllar, and he received a leg wound from a knife-thrust, before the old man intervened.

De Cuéllar was stripped of his clothing, and a gold chain worth 1,000 ducats and 45 gold crowns were taken from him. The young woman ensured his clothes were returned, and took a locket containing relics, which she hung about her neck, before departing. Then a boy came to treat his wounds with a poultice and brought food of milk, butter and oaten bread.

Heeding the boy's warning not to approach the village, de Cuéllar limped past and went on his way alone, living off berries and watercress. He was set upon by a group of men who beat him hard and stripped him of his clothes; he covered himself with a skirt of plaited ferns and rushes. He came to a deserted settlement at the edge of a lake, where he was surprised to find three other Spaniards. Having stayed some time at the settlement, the group met a young man who spoke Latin and directed them to the territory of Sir Brian O'Rourke in Leitrim.

O'Rourke's country

In O'Rourke's country they found greater safety, at "a village belonging to better people, Christian and kindly", where 70 Spaniards were enjoying refuge. Dressed in lice-infested cloak and trousers, Cuéllar set off northward in a party to meet with a Spanish ship at anchor for repairs, but was disappointed to hear the ship had already sailed. He returned to O'Rourke's country, where he was entertained by the lord's wife, who he described as "very beautiful in the extreme, and she showed me much kindness".

She took a shine to the Spaniard's ability for telling fortunes: ″One day we were sitting in the sun with some of her female friends and relatives, and they asked me about Spanish matters and of other parts, and in the end it came to be suggested that I should examine their hands and tell them their fortunes. Giving thanks to God that it had not gone even worse with me than to be gipsy among the savages, I began to look at the hands of each, and to say to them a hundred thousand absurdities, which pleased them so much that there was no other Spaniard better than I, or that was in greater favour with them. By night and by day men and women persecuted me to tell them their fortunes, so that I saw myself (continually) in such a large crowd that I was forced to beg permission of my master to go from his castle.″[2]

Cuéllar observed the society, noting that the people lived in a savage manner, but that they were friendly and followed the usages of the church. The people constantly engaged in nightly raids and were harried by English garrisons. He reckoned that, were it not for their hospitality, he and his fellows would not have lived: "As to ourselves, these savages liked us well because they knew we came against (to oppose) the heretics, and were such great enemies of theirs; and if it had not been for those who guarded us as their own persons, not one of us would have been left alive. We had goodwill to them for this, although they were the first to rob us and strip to the skin those who came alive to land". He concluded: "In this country there is neither justice or right, and everybody does what he likes" (Kilfeather, p. 83).

Siege at Rosclogher

In November 1588 Cuéllar moved on to the territory of the MacClancy with 8 other Spaniards, staying at one of the lord's castles – probably at Rosclogher on the south of Loch Melvin. News arrived that the English had sent 1,700 troops to MacClancy's country. In response, the lord opted to take to the mountains, while the Spaniards resolved to defend the castle. They had 18 firearms – muskets and arquebuses – and considered the castle impregnable because of its location in bogland, which precluded the use of artillery.

The English arrived under the command of the brother of Richard Bingham, governor of Connacht, and the siege lasted 17 days. During that time they were unable to cross the boggy terrain and, having had their offer of safe passage to Spain turned down, they hanged two Spaniards in full view of the castle so as to terrorise the defenders. A storm closed in with heavy snow, and the English were forced to raise the siege and march off.

MacClancy returned and bestowed gifts on the defenders, including an offer to Cuéllar of the hand of his sister in marriage, which was declined. Against the chieftain's advice, the Spaniards secretly departed his country ten days before Christmas, bound for the north. They sought out the bishop of Derry, Redmond O'Gallagher, and found he had twelve other Spaniards in his care, whom he intended to assist in a crossing to Scotland.

Escape

After six days, Cuellar and 17 others set sail for Scotland in a pinnace. Two days later they reached the Hebrides, and soon after landed on the mainland. Cuéllar remained in Scotland for 6 months, until the Duke of Parma's efforts procured him passage to Flanders in the Low Countries. However, the Dutch were waiting on the coast to cut off the return of Armada survivors, and Cuéllar was shipwrecked in a firefight in which many of the survivors were drowned or killed after capture. Once again he found himself clinging to flotsam as he came ashore in Flanders, where he entered the city of Dunkirk wearing only his shirt. He wrote an account of his experiences and returned to Spain some time after.

O'Rourke was hanged at London for treason in 1590; the charges against him included succouring survivors of the Armada. MacClancy was captured by Bingham's brother in 1590 and beheaded.

Life after the letter

After the Armada Cuéllar served in the army of Philip II under Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, Count Fuentes and Count Mansfeld. Between 1589 and 1598 he served variously in the Siege of París, the enterprises of de Laón, Corbel, Capela, Châtelet, Dourlens, Cambrai, Calais, and Ardres, and in the siege of Hults. In 1599 and 1600 he served under Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy in the war of Piemonte. In 1600 he was in Naples with viceroy Lemos.

In 1601 he was commissioned to return to America. He was a pattern of infantry captain in a galleon to islas de Barlovento (Windward Islands), but didn't sail in don Luis Fernández de Córdova's navy until 1602.

It was Cuéllar's last military service. He lived in Madrid in the period 1603–1606, hoping for new commissions in America.

Nothing is known about Cuellar's death or whether he had any children.

References

- T.P. Kilfeather Ireland: Graveyard of the Spanish Armada (Anvil Books, 1967)

- Online version of Cuellar's account

- Francisco And The Chieftain's Wife by J.P. Rooney (Ireland, 2007). Novel inspired by Francisco's own narrative

- El capitán Francisco de Cuéllar antes y después de la jornada de Inglaterra, by Rafael M. Girón Pascual

External links

![]()