Fort Weld

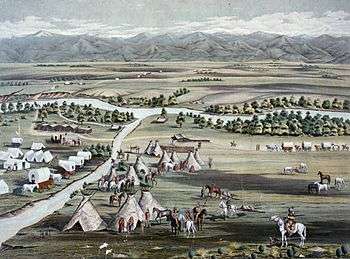

Fort Weld, also called Camp Weld, began as a military camp on 30 acres east of the Platte River in what is now the La Alma-Lincoln Park neighborhood of Denver, Colorado.[1] It was named for Lewis Ledyard Weld, the first Territorial Secretary. The central square of the post was used to practice drills of the troops. Buildings—soldier's quarters, officers' headquarters, mess rooms, a hospital, and a guard house—surrounded the square. The main entrance to the camp was on the eastern side of the post.[1] It was established on September 1861 and abandoned in 1865.

Civil War

Governor William Gilpin had it built in 1861 to protect the territory from attack by the Confederate soldiers during the Civil War. After the Battle of Fort Sumter, tensions from people of the north and south resulted in brawls in the bars and streets of Denver and there were rumors that a brigade from Texas was marching towards Colorado.[1] Soldiers of the 1st Colorado Infantry Regiment trained at Camp Weld and was credited with preventing advance of Texan troops in the Western United States.[1] John Chivington was a commander of the post.[2]

Native Americans

Arapaho and Cheyenne leaders met at Camp Weld in September 1864.[3] Called the Camp Weld Council, it was a peace talk with the tribes and representatives from the Colorado Territory and the United States Army,[4] Silas S. Soule, militia commander John Chivington, territorial governor John Evans and Major Edward W. Wynkoop.[4][5] The council was intended to bring peace between the native tribes and the European settlers and the Arapaho and Cheyenne leaders thought that they complied with the peace terms. However, efforts by Evans and the Sand Creek massacre (November 29, 1864) led by Chivington was "a deep moral failure", according to a study by eight scholars from Northwestern University and other universities.[6]

Former camp

There were two fires that destroyed the camp. One soldier staked a homestead claim on Officer's Row, the last standing section of the camp. He raised his family there and built fish ponds and planted orchards on the land. He operated a picnic ground and a market for years.[1]

A bronze and granite historical marker was erected at 8th and Vallejo in 1934, which says:[1]

This is the southwest corner of Camp Weld. Established September 1861 for Colorado Civil War Volunteers. Named for Lewis L. Weld, First Secretary of Colorado Territory. Troops leaving here February 22nd, 1862 won victory over Confederate forces at La Glorieta, New Mexico. Saved the Southwest for the Union. Headquarters against the Indians 1864-65. Camp abandoned 1865.[1]

References

- "Camp Weld – A Tale of Denver's Birth". Lincoln Park History. December 9, 2014. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- Beardsley, Isaac Haight (1898). Echoes from Peak and Plain, Or, Tales of Life, War, Travel and Colorado Methodism. Curtis & Jennings. p. 250.

- "Arapaho and Cheyenne Delegation at Camp Weld, 1864". coloradoencyclopedia.org. March 29, 2016. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- "Art And Healing: The Sand Creek Massacre 150 Years Later". NMAI Magazine. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- "Behind the Marker at 15th and Arapahoe: The Life of Silas Soule". Denver Public Library History. April 10, 2017. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- "John Evans and the Sand Creek Massacre". Northwestern Magazine - Northwestern University. Retrieved February 7, 2020.