Fort Manhassett

Fort Manhassett was a group of earthen fortifications that guarded the western approaches to Sabine City, Texas during the American Civil War, operating in service of the Confederate Army from October 1863 to May 1865.

| Fort Manhassett | |

|---|---|

| Sabine City, Texas in United States |

Background

By the time Fort Manhassett's construction was complete, Texas had long been a target for attempted Union occupation.[2] President Abraham Lincoln's blockade of southern ports threatened to cut off the Confederacy's foreign supply of desperately needed arms, powder, and lead. By late 1862, Galveston, Texas's largest city and a port vital to Confederate Texas's war effort, had been occupied by Federal forces, and Sabine City had been subjected to raids and harassing bombardments from Union Navy Lt. Frederick Crocker's expedition.[3] Maj. Gen. John Bankhead Magruder recaptured Galveston on January 1, 1863, and later in the month, Confederate cottonclad gunboats temporarily lifted the blockade at Sabine Pass.[4]

In the summer of 1863, US President Abraham Lincoln, fearing an alliance between the French government in Mexico and the Confederacy, ordered the invasion of Texas.[5] After some deliberation in planning the actual site of the invasion, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks directed Maj. Gen. W.B. Franklin to plan for the landing of an amphibious expeditionary force to establish a base of operations for the invasion and occupation of Texas.[6] A fleet of nineteen transports carrying about 5000 Federal troops was assembled in New Orleans.[5] Escorted by six gunboats mounting heavy guns to support the landings, the fleet got underway and sailed for Sabine Pass.

On September 8, 1863, a company of 42 immigrant Irish dockhands from Galveston, under the command of a young Lt. Richard W. Dowling, were manning six antiquated cannon in an earthen fortification, known as Fort Griffin, at Sabine Pass.[7] On the evening of the 7th, the Federal fleet arrived off the bar and sent four gunboats up the pass (rather than six, due to the shallow waters of the Sabine River) to neutralize the fort.[6] Dowling withheld the fire of his guns until the Federal vessels came within close range, then opened fire. After watching Dowling's gunners maul three gunboats, and fearing rebel gunboats and field artillery, the Union fleet retreated and returned to New Orleans, without ever disembarking its troops. Dowling had captured two gunboats with heavy cannon and captured approximately 300 prisoners, without the loss or injury of a single Confederate.[5]

CS commanders later realized that had the Federals attempted to land troops further to the southwest rather than sending their gunboats up the killing zone of the pass, Fort Griffin would have been turned and become useless to resist the invading force.[6] Having painfully realized their oversight, the Confederate authorities immediately began plans to construct a line of fortifications to secure and defend this unprotected 'back door' to Sabine City.[8]

Design, Construction, and Characteristics

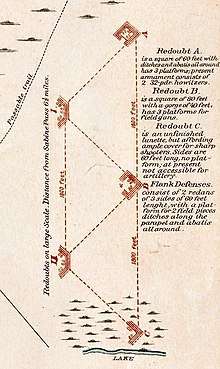

Fort Manhassett's siting and construction was built with a keen eye to the tactical terrain of the marshy plains west of Sabine City. To this day, the area consists of flat salt grass prairie with numerous marshes and several large shallow lakes inland of the beach. These large lakes are generally 6–8 feet (1.8–2.4 m) at their deepest, and the marshes support a huge variety of wildlife. The mile of open ground between Knight's Lake and the beach was selected as the site for the fort, as it was a natural chokepoint, with the road on Sabine Ridge providing a route of resupply and communication with the town. Colonel Valery Sulakowski, chief engineer of the Confederate engineering department in Texas, ordered his subordinate, Major Julius G. Kellersberger, to begin the construction of a series of redoubts, redans, and lunettes on the mile of open saltgrass prairie between Knight's Lake and the Gulf of Mexico.[8] Fort Manhassett consisted of two redoubts, two redans, and one lunette. Redoubt A, Redoubt B, and Redoubt C were built on a straight line, running north to south, between the beach road and the southern shore of the lake. The three redoubts were built to contain a possible enemy advance from the west, and mounted several heavy cannon for that purpose. The two redans in the rear, labelled Flank Defenses I and II on Kellersberg's 1863 map of the Sabine defenses, were intended to serve as a second line of defense in the event of the advance works falling to an attacking enemy. The shell road from Galveston to Sabine City ran between Redoubts A and B. Redoubt C, which was actually a redan, was sited in the marsh, making it inaccessible for artillery when first built;[9] however, it is possible that corduroy roads were later built to allow heavy weapons to be mounted in the work, much in the same manner that machinery and pipe fittings are transported to modern LNG terminals in the salt marshes of the Texas coast.

All the forts were built of sand and oyster shell, and based on descriptions of the earthen, semi-permanent fortifications at Galveston, had their works covered with sod.[10] They were built by using slave labor,[11] and supporting framing was presumably constructed using timber and planks from the federal collier Manhassett. This was a civilian, schooner-rigged vessel out of Boston, Massachusetts, under contract to supply coal to the blockade ships of the Union Navy. During a severe storm on the night of September 19, 1863, Manhassett ran aground on the sandbar near the site of the new fort.[12] On the morning of its discovery by the Confederates, the wreck was immediately seized, and her civilian crew of seven men were taken prisoner. They were eventually interred at Camp Groce, near Hempstead, Texas.[13]

On the morning of September 30, the US gunboat Cayuga approached the wreck close enough to ascertain that it was Manhassett, and upon sighting Confederate cavalry on the beach nearby, she fired a total of six shells from her 30-pounder and 20-pounder rifled guns. Cayuga was in turn fired upon by a Confederate battery of three guns on the beach. After sighting Confederate gunboats up the pass ready to give battle, Cayuga stood down[12] and sent a boat ashore under flag of truce to inquire as to the condition of the wreck and the fate of the crew.[12] Ironically, Manhassett had supplied the Federal gunboats attacking Fort Griffin with coal about two weeks before she was captured by the Sabine garrison.[12] Though never mentioned specifically in any known reports or letters, it is generally assumed that since the fort was built near the site where Manhassett ran aground, its name was taken from the ship.[14]

Fort Manhassett's works were constructed along the same principles and theories that had been taught to US Army engineers for decades. The works were generally up to 15 feet (4.6 m) in height, from 60–80 feet (18–24 m) along the sides, and 15–20 feet (4.6–6.1 m) thick at the parapets. They were further protected by ditches surrounding the works, abatis, and rifle trenches and breastworks.[15]

It is not known if the plans for the forts survived the war; their design plans were mentioned by Colonel Sulakowski as being in the possession of Major Hugh T. Douglas of the engineering department.[8] Many of the surviving original plans of neighboring forts, especially those in Galveston, bear the signature of Major Douglas, but unfortunately, no designs or plans of Fort Manhassett turned up in the Gilmer Civil War Maps Collection.[7]

Confederate Service 1863-1865

Fort Manhassett has been dubbed a 'quiet piece of history' by Sabine Pass residents, and indeed, no known combat occurred there. The main enemy to the Confederates in garrison there was boredom and disease. In spite of poor army rations, the garrison presumably subsisted well on the plentiful ducks, geese, rabbits, and fish in the surrounding marsh and beach. However, in April 1864, Fort Manhassett's defenders would receive their baptism of fire 35 mi (56 km) to the east at Calcasieu Pass, Louisiana.

On April 14, 1864, two Federal gunboats, USS Wave and USS Granite City, sailed into Calcasieu Pass and anchored on the horseshoe bend across from what is now Monkey Island. Almost as soon as the boats anchored, a Confederate loyalist rode to Sabine City and notified the Confederate authorities of their presence. The gunboats' mission was simply to gather beef to feed the sailors of the blockade fleet, and to recruit for the Union Navy.[16] However, their relatively innocuous intentions were of little concern to Major General John B. Magruder, after being notified of the situation, ordered a force to attack and capture the vessels immediately. The forces assembled to attack the gunboats were composed of Colonel Ashley W. Spaight's[17] 11th Texas Infantry (companies A, B, C, and D), based at Niblett's Bluff, and Colonel W.H. Griffin's 21st Texas Infantry (companies A, C, and E, commanded by Major Felix McReynolds), twenty cavalrymen of Daly's Company of the Fourth Arizona Cavalry, and Captain Edmund Creuzbauer's battery of two 6-pounder and two 12-pounder guns.[16] Colonel Griffin's force moved from Fort Manhassett to Sabine City, and was transported by steamer to Johnson's Bayou, Louisiana. After debarking there, the infantrymen and cannoneers marched the 30 mi (48 km) all night along Blue Buck Ridge to Calcasieu Pass, going straight into the attack at 5 AM.

The Confederates discovered the Federal boats lying at anchor with no steam in their drums; after a sharp three-hour battle, both vessels surrendered and were boarded by the Confederates.[18] The two ships were recovered by the Confederates and outfitted as blockade runners. Rebel casualties were 14 killed and 9 wounded; it is unknown how many Union sailors and marines died. However, according to Colonel Griffin's report of May 11, 1864, there were an estimated 15 to 20 Union dead.[19] USS Granite City had been one of the two surviving Union gunboats that had participated in the ill-fated assault on Fort Griffin on September 8, 1863.

Garrisons

The Trans-Mississippi Department, under command of Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith was widely known as 'Kirby-Smithdom', in reference to the department's size and isolation. This was a result of the losses of New Orleans and Vicksburg, which restored Union control of the Mississippi River, effectively halving the Confederacy's territory. As such the department did not receive much assistance from the Confederate capitol in Richmond.

Major General Magruder, concerned with keeping open the ports used by blockade runners and defending the Texas coast from seaborne invasion,[11] had 3,636 men (nearly 40% of his entire command) in garrison at Sabine Pass, by September 1863.[8] According to the post inspection report of Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Allston dated October 14, 1863, Fort Manhassett was garrisoned by two infantry companies (Major Felix C. McReynolds commanding) of the 21st Battalion, Texas Infantry, two companies of cavalry from DeBray's Cavalry Regiment, and Nichols' Texas Battery (Captain William H. Nichols commanding).[8] Though no solid numbers are available for the strengths of these units, there were likely several hundred men in garrison at Fort Manhassett at that time.[14]

By March, 1864, Nichols' Battery was relieved and replaced by Creuzbaur's Battery of German immigrants from Fayette County, Texas. Shortly after their participation in the fight at Calcasieu Pass, Creuzbaur's Battery was renamed Welhausen's Battery, and ordered to report to Liberty, Texas. Before their transfer, they were ordered to mount two 24-pounder brass Dahlgren howitzers (captured from Granite City[14]) on barbette carriages for installation at Fort Manhassett.[20] The Germans were relieved by the recently retrained artillerists of Company B, Spaight's 11th Texas Battalion.[14] Despite the merging of Spaight's and Griffin's infantry battalions into the 21st Texas Infantry Regiment in November, 1864, Company B was redesignated Co. I of Bates' 13th Texas Infantry Regiment.[14]

Fort Manhassett's strength appears to have dwindled during the last months of the war. This was likely due to transfers, desertions, and deaths from disease. The post return for April 20, 1865, with Major McReynolds then in command of the entire Sabine post, showed only 48 men and officers of the 13th Texas Infantry present for duty at Fort Manhassett; on May 10, 1865, 51 men of the 13th Texas, along with 45 men of the Fourth Brigade, Arizona Brigade were standing duty.[21] A Federal army report, dated May 13, 1865, mentions the report of a deserter from Sabine Pass that Fort "Manchassee" was held by an estimated 65 men, and mounted eight guns.[22]

While the rebel armies to the east fought against overwhelming odds in titanic battles in Virginia, Georgia, Tennessee, and the Carolinas, the remainder of the war at Sabine Pass was spent guarding the coastline from an enemy who was ever expected but never came again after September 1863. The blockade runners continued to slip by the Federal blockade, and the Union never again attempted a landing on the upper Texas coast. When Lee and Johnston surrendered in April 1865, effectively ending the war, the news did not reach Sabine Pass until the end of May.[5] Many Confederate officers simply told their men to go home. At Fort Manhassett, the Confederate standard was lowered for the last time, and some of the remaining guns, ammunition, and powder were pushed or thrown into the ditches and buried.[14] On May 25, 1865, Acting Volunteer Lieutenant Lewis L. Pennington of the US Navy, and a former resident of Sabine Pass, came ashore with a landing party of marines and raised the Union flag over Forts Manhassett and Griffin; interestingly, only four guns were reported to have been mounted at Fort Manhassett.[8]

Postwar Activities at the Site

After it was abandoned at the end of the Civil War, Fort Manhassett's earthen ramparts became overgrown and blended in to the marshy terrain in which they were built. Being isolated, seven miles away from the nearest settlement, the works were gradually claimed by nature. Local lore indicates that townspeople salvaged timbers and reusable materials from the works, similar to the fate of Fort Griffin.[5]

An 1864 drawing of the defenses of Sabine Pass showed a "road from Galveston," and Confederate engineers had apparently sited Redoubt A within a curve of the road.[1] In 1926, the road was graded and straightened, which resulted in approximately 30 large-caliber artillery munitions and kegs of black powder being unearthed.[23] The ordnance was presumably reburied, as five decades later, several cannonballs were unearthed, at a depth of only one foot, by road machinery at the site.[14]

In August, 1970, road construction machinery working on the road, now designated State Highway 87, began uncovering artifacts from the site of Redoubt A. A total of approximately 200 32-pounder cannoballs[14] and an unknown number of canister shot or grapeshot were eventually recovered by amateur diggers. The uncovering of the ordnance prompted the arrival of an explosive ordnance demolition team from Fort Polk, and some of the rounds and black powder were reportedly transported to the base.[24] Other artifacts recovered included square nails, "lumber" (presumably from the wall supporting the interior slope of the work), and "a mechanism used to aim a cannon in the proper direction" (presumably a handspike).[23] Though this work was ostensibly under the direction of W.T. Block, a prominent local historian, it is unknown what has become of nearly all these artifacts; however, a few examples of the recovered ordnance have made their way into the collection of Port Arthur's Museum of the Gulf Coast.[25]

An interesting anecdote from a 2006 archaeological survey of an area close to McFadden Beach mentions the purposeful destruction of the site by a souvenir hunter:

[A state archaeologist, in the early 1970s] tried to persuade the man from digging into the site with a backhoe and destroying the site. The digger claimed to be the landowner. The digger chided [him] saying he was just trying to get the site for himself. When the digger’s backhoe bucket exposed some unexploded ordinance (sic), [the archaeologist] persuaded the digger to witness a demonstration of the potential danger to the digger and his backhoe. [The archaeologist] carried one of the cannonballs a short distance away and cut a hole in the bomb’s lead plug. Then he removed some crystalline granules and ignited them. The powder (100 years old!) ignited with an impressive loud burst of flame and smoke. The landowner climbed onto his backhoe and drove away.[26]

The site of Fort Manhassett currently lies on private property. The remains of Redoubt B and both Flank Defenses are easily seen in aerial imagery, with a corner of Redoubt A being visible, and Redoubt C being entirely underwater. As of 2019, the site continues to be grazing land for cattle, and as such, the site is in a form of preservation.

References

NB - note that 'OR' and 'ORN' in the references list refer to Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Armies, and Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Navies, respectively.

- OR, Series 1, Vol XXXVIII, Part 2, Atlas, OR, Plate XXXII 'Plan of Sabine Pass, of its Defenses and Means of Communication', accompanying report of Maj. JP Johnson, IG, OR Series 1, Vol. XXII, Part 2

- "The Civil War in Texas". Austin Community College. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- Wooster, Ralph. "Sabine Pass, TX". TSHA:Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- Barr, Alwyn. "Sabine Pass, TX". TSHA:Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- Cotham, Edward. Sabine Pass: The Confederacy's Thermopylae (2004).

- OR, Series 1, Vol.XXVI, Part 1

- "About the Gilmer Civil War Maps". Gilmer Civil War Maps Collection. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- OR, Series 1, Vol.XXVI, Part 2

- Atlas, OR, Plate XXXII 'Plan of Sabine Pass, of its Defenses and Means of Communication', accompanying report of Maj. JP Johnson, IG, OR Series 1, Vol. XXII, Part 2

- "Fort Magruder (2)". Fort Wiki. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- Hall, Andrew W. Civil War Blockade Running on the Texas Coast. Charleston, SC: The History Press.

- ORN, Series 1, Vol. 20

- Lisarelli, Read; 'The Last Prison: The Untold Story of Camp Groce, CSA; Chapter 5, p 39

- Fort Manhasset: A Forgotten Chapter in the History of Sabine Pass, Texas WT Block, Jr. Website. Retrieved 11 April 2019

- Hess, Earl J. Field Armies and Fortifications in the Civil War. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press

- Battle of Calcasieu Pass, Louisiana WT Block, Jr. Website. Retrieved 11 April 2019

- Spaight, Ashley W. TSHA:Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 11 April 2019

- Smith, Myron. Tinclads in the Civil War: Union Light-Draught Gunboat Operations on Western Waters, 1862-1865. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

- OR, Series 1, Vol. XXXIV, Part 1

- Boethel, Paul. 'Big Guns of Fayette' (1965).

- OR, Series 1, Vol.XLVIII, Part 2

- OR, Series 1, Vol.XLVIII, Part 1

- McMurray, Kim (1970-08-17). "Fort Manhassett Rivaled Dick Dowling's Ft. Griffin But Only Now Gains Fame". Beaumont Enterprise.

- McMurray, Kim (1970-09-02). "Old Fort Work Recovers More Cannon Balls". Beaumont Enterprise.

- "Museum of the Gulf Coast". Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- "An Archaeological Survey of Two Borrow Pit Areas: Tract 1 (Gabby's Pit) and Tract 3 (Doornbos Pit) in South East Jefferson County Texas" (PDF). Retrieved 12 April 2019.