Fontaine Fox

Fontaine Talbot Fox, Jr. (June 4, 1884 – August 9, 1964) was an American cartoonist and illustrator best known for writing and illustrating his Toonerville Folks comic panel, which ran from 1913 to 1955 in 250 to 300 newspapers across North America.

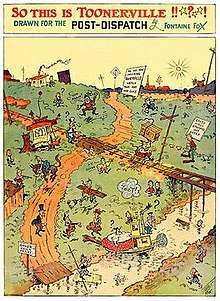

The cartoons are set in the small town of Toonerville, which appears to operate in its own little universe. The gentle humor of the feature dealt with the antics of the various denizens and featured semi-realistic situations. It was one of the most popular comics during the World War I era.

Life before Toonerville

Born near Louisville, Kentucky, Fox started his career as a reporter and part-time cartoonist for the Louisville Herald. He spent two years in higher education at Indiana University, Bloomington; nevertheless, he continued sketching one cartoon a day for the Louisville Herald. After two years of college, he abandoned his studies in favor of his true calling, writing and illustrating comics. From 1908, Fox started a series of daily cartoons about kids for the Chicago Evening Post. His panel was noted by the Wheeler Syndicate, which started distributing his work nationwide, this eventually led to the creation and distribution of Toonerville Folks. The panel, which expanded its circulation from a few papers to hundreds between 1915 and the mid-1920s, spawned several merchandising efforts, including cartoon books, cracker boxes, magic picture folders, paper masks, gum wrappers, bisques and cutout sheets.[1]

Unique style

His work was considered innovative for many reasons. He presented the panel in a rather distinctive illustration style. At first glance, Fox's drawing style seems deceptively simple, but under scrutiny, bits of his interesting technique become apparent. Vehicles and telephone poles are oddly tilted and, frequently, so is the horizon. He also illustrated his cast and landscape with a slight aerial perspective, so that it always seemed that the reader was looking down at the events of each tale. From this panoramic perspective, readers could fully absorb the antics of town regulars, which included an entire farming community filled with colorful characters of varying ages. The comic panel included the largest cast ever seen in a comic strip, 53 different characters in all. Fox has been described as an ingenious caricaturist, simply because all of his figures are grotesquely exaggerated. According to Fox, "In drawing a cartoon I always try to keep three things in mind—it must have an original thought: it must be something that has happened or could happen: and it must be laughable. That's all there is to it!"

Toonerville in the movies

Founded by Siegmund Lubin, the Betzwood Motion Picture Studio in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, operated between 1912 and 1923. Over 100 films were produced at the 350-acre studio, which was run by the Wolf Brothers, Inc. of Philadelphia beginning in 1917. In 1920 and 1921, 17 Toonerville Trolley two-reel comedies were made at Betzwood. Only seven of these survive today.

In 1936, Van Beuren Studios produced three animated cartoon shorts about the Toonerville folks as part of Burt Gillett's Rainbow Parade series; however, they never matched the success of the panel. What did succeed was the decision to make Mickey McGuire the star of a series of low-budget live-action shorts, getting into adventures with other back-alley kids, which led to more than 50 short silent black and white film comedies.

Joe Yule Jr., son of vaudeville comedian Joe Yule and Nellie W. (née Carter) Yule, auditioned for the role and landed the part. He was promptly renamed Mickey McGuire and starred as himself. When the young boy actor and the role parted company, Fox would not allow the juvenile to continue performing under Mickey McGuire, so Joe Yule Jr. / Mickey McGuire changed his name once more, this time to Mickey Rooney.

The Mickey McGuire shorts have a very similar feel to the Hal Roach studio's Our Gang shorts. Produced by Larry Darmour during the same period, they have many of the same flaws, such as racist gags at the expense of an African American member of the gang; however, the McGuire shorts benefited from the strong presence and talent of the young Mickey Rooney.

Inspiration

No less than two cities claim to be the inspiration of Toonerville Folks: Louisville and Pelham, New York. The folks of Louisville claim the experiences were based on the short Brook Street Line in 1915, which ran until 1930. For years, this route had been getting the cast-off equipment from the trunk lines until it became the joke of the town. Finally, the managing editor of the Louisville Herald asked the young Fox to draw some sketches caricaturing the antiquated vehicles, which is said to have cast the germ for the Toonerville Trolley.

However, the Pelham populace insists the comic strip was based in part on the artist's experience during a trolley ride on a visit to Pelham in 1909. They alleged that Fox repeatedly said that he was inspired to create the Toonerville Trolley and its skipper based on a trolley ride he took in Pelham. During that ride, he observed the trolley car operator gossip with passengers and, once, stop the vehicle to pick apples in an adjacent orchard. One piece of that evidence is an article that appeared in The New York Times on July 30, 1937, the day before the last journey of the Pelham trolley due to its replacement by a bus route. The article reported, among other things, that Mr. Bailey piloted the Pelham trolley from 1900 to 1914. According to the article:

- Back in 1909, when Mr. Fox took a ride on the Pelham line, then served by a rickety little car, he watched the "skipper" gossip with the passengers and stop the car to pick apples for them; thus he drew his inspiration for his Toonerville Trolley comics.

Fox continued the Toonerville Folks comic panel until 1955, changing syndicates twice, eventually gaining all rights to his comic panel. He later moved to New York City. During the 1940s, he lived at One West Elm Street in Greenwich, Connecticut, spending winters at 610 North Ocean Boulevard in Delray Beach, Florida. Jack Morley, an assistant with Fox, also worked with Crockett Johnson on Barnaby.

Apart from drawing comics, he was an author and a fervent golfer, winning several tournaments. His cartoons ran for 42 years and were honored in a 1995 U.S. postage stamp series. Upon retirement, he refused to let his brainchild pass into another cartoonist's hands. Fox died at the age of 80 in Greenwich in 1964. His epitaph reads, "I had a hunch something like this would happen."

Books

Fox did three books, Fontaine Fox's Funny Folk (1917), Fontaine Fox's Cartoons (1918) and The Toonerville Trolley and Other Cartoons (1921), as well as illustrating several others, notably for Ring W. Lardner, including Own Your Own Home (1919) and Bib Ballads (1915).

Archives

The Filson Historic Society of Louisville, whose mission is to collect, preserve and tell the significant stories of Kentucky and the Ohio Valley history and culture, boasts a collection that includes photographs of Fox as a child, the family home at Hubers Station, Kentucky, Fox, his wife and their daughters.[2]

The Fox collection of 2,574 items is located at Indiana University. It consists of papers from Fox, including correspondence, original drawings of the cartoons and scripts of books and series. Printed material includes the prints of the syndicated Toonerville Trolley comic strip and biographical information.[3]