Flea flicker

A flea flicker is an unorthodox play, often called a "trick play", in American football which is designed to fool the defensive team into thinking that a play is a run instead of a pass.[1] It can be considered an extreme variant of the play action pass and an extension of the halfback option play.

Description

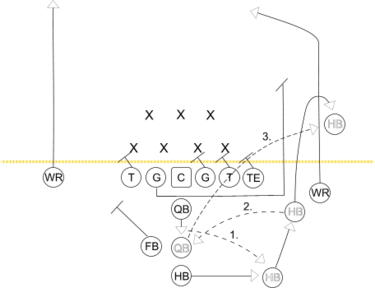

After the snap the quarterback hands off or laterals the football to a running back or another player on his team, who then runs towards or parallel to the line of scrimmage. Before the running back crosses the line of scrimmage, he laterals the football back to the quarterback, who looks to pass to an eligible receiver.[2][3]

The play is designed to draw defensive players into defending against the run, and away from defending the pass, leaving the quarterback free from any immediate pass rush, and leaving receivers potentially open to catch a pass as their covering defenders may have moved off the pass looking to tackle a ball carrier. The elaborate back-and-forth with the ball also gives time for receivers to get downfield, opening up an opportunity for the long bomb.

The flea flicker is an extremely high-risk play and one that is extremely difficult to pull off successfully; a failed flea-flicker can cause substantial loss of yardage or a turnover. The problem is that it takes a significant amount of time for the play to develop. This poses two related problems: one, the offensive line, in order to convincingly sell the run, cannot set up the traditional pocket until after the running back pitches the ball back to the quarterback, and if any lineman crosses the line of scrimmage, it is an ineligible player downfield, negating the play. Two, the long time involved in the handoff, run and pitch back to the quarterback takes away time for the quarterback to make his reads (as he must watch for the ball coming his way so that he doesn't drop the ball instead of scan the defense). This makes the quarterback far more prone to being sacked or making a bad read of the defense and throwing an interception. The fact that the ball changes hands three times after the snap (as opposed to one on a typical play) also means that there are three opportunities to lose possession of the ball because of a botched throw or catch attempt.

Origins

Illinois coach Bob Zuppke is credited with the play's invention.[4][5][6] The flea flicker made its debut in Illinois' 1925 game against Penn as a fake field goal with Earl Britton, Red Grange, and Chuck Kassel; with Britton lining up as a kicker and Grange at holder, the former and threw to Kassel, who lateraled the ball to Grange. Grange would score a 20-yard touchdown on the play.[7]

Notable examples

Flea flicker plays have been used in some key National Football League games, including the Super Bowl, leading to dramatic results:

- January 12, 1969: In Super Bowl III, just before halftime, the Baltimore Colts, trailing 7–0 to the New York Jets, tried a flea flicker, but despite the fact that Jimmy Orr was wide open near the end zone, Earl Morrall threw the ball to fullback Jerry Hill. Jets safety Jim Hudson ended up intercepting the pass. During a regular-season game against the Atlanta Falcons, Morrall used the same play and was able to find Orr for a touchdown.

- January 30, 1983: In Super Bowl XVII, the Washington Redskins used a flea flicker to try to fool the Miami Dolphins to no avail. Mindful of the ruse, Miami defensive back Lyle Blackwood intercepted the pass. However, Washington coach Joe Gibbs later pointed out the play was not a total loss, as Blackwood was downed on his own 1-yard line. Washington ended up forcing Miami to punt from deep in their own territory and got the ball back with great field position, setting up a touchdown drive.

- November 18, 1985: Joe Theismann of the Washington Redskins infamously had his career come to an end on a nationally televised Monday Night Football game at the hands of New York Giants linebacker Lawrence Taylor. The play in question was a flea flicker attempt which failed to fool the Giants’ defense. When Taylor tackled Theismann, his entire weight came crashing down on Theismann, severely breaking his leg.[8]

- January 25, 1987: In Super Bowl XXI, the New York Giants successfully ran a flea flicker play against the Denver Broncos: Quarterback Phil Simms passed the ball to receiver Phil McConkey, who ran all the way to the Broncos 1-yard line before being tackled for a 44-yard gain. The Giants scored a touchdown on the next play.

- January 3, 2009: During the NFC Wild Card, Kurt Warner successfully completed a flea flicker against the Atlanta Falcons with running back Edgerrin James and wide receiver Larry Fitzgerald. Warner and the Arizona Cardinals were finding early success running the ball in the first quarter of the game, so Warner handed the ball off to James, who ran about 2 yards towards the line of scrimmage and then turned and pitched the football back 5 yards to Warner. The pitch was almost unseen as the safeties and linebackers had their views blocked by the defensive line, which was collapsing on the running play. The play ended with a 50-yard throw (42 yards officially from the original line of scrimmage) to Fitzgerald, who jumped backwards in the air while in double-coverage to make the catch in the front left corner of the endzone for the touchdown, which helped the Cardinals to take an early 7–0 lead in the game, and ultimately win their first playoff game in 10 years, and their first home playoff game in over 60 years.

- January 18, 2009: In the NFC Championship, Kurt Warner successfully completed a flea flicker play against the Philadelphia Eagles with running back J.J. Arrington and wide receiver Larry Fitzgerald. Warner passed to Arrington, who passed back to him. Warner then completed a 62-yard throw to Fitzgerald to complete the touchdown, which helped the Cardinals to increase their lead 14–3 and finish 32–25.

- December 4, 2011: In the first game after acquiring quarterback Kyle Orton off waivers, Kansas City Chiefs starter Tyler Palko was benched due to ineffectiveness in the beginning of the second quarter in favor of Orton. The first play run for Orton was a designed flea-flicker, but strong safety Major Wright of the Chicago Bears struck Orton as he threw, causing the pass to fall incomplete and injuring Orton's finger, causing him to miss the remainder of the game. The Chiefs ended up winning 10–3.

- January 21, 2017: The New England Patriots ran a flea flicker with 7:53 left in the 2nd quarter of the AFC championship game against the Pittsburgh Steelers. Tom Brady handed the ball to running back Dion Lewis on what appeared to be a basic run on first-and-10. But as Lewis approached the line of scrimmage, he stopped and pitched the ball back to Brady, who scanned the field and found a wide-open Chris Hogan for a 34-yard touchdown strike to give the Patriots a 17–6 lead. The Patriots won the game 36–17 en route to their fifth Super Bowl championship.[9]

- January 21, 2018: The two conference championship games included three successful flea-flicker plays. First, in the American Football Conference championship, Jacksonville Jaguars quarterback Blake Bortles handed off to T.J. Yeldon, who tossed the ball back to Bortles. Bortles then passed to Allen Hurns for a 20-yard gain against the New England Patriots. Later in the fourth quarter, the Patriots retaliated with a flea-flicker pass from Tom Brady to Phillip Dorsett for 31 yards. Finally, in the National Football Conference championship, with the Philadelphia Eagles leading the Minnesota Vikings by 24-7, Eagles RB Corey Clement flicked the ball back to QB Nick Foles, who completed a 41-yard touchdown pass to WR Torrey Smith.[10][11]

References

- Hickoff, Steve (1 August 2008). The 50 Greatest Plays in Pittsburgh Steelers Football History. Triumph Books. ISBN 978-1-63319-081-8 – via Google Books.

- Musiker, Liz Hartman (29 July 2008). The Smart Girl's Guide to Sports: An Essential Handbook for Women Who Don't Know a Slam Dunk from a Grand Slam. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-452-28950-5 – via Google Books.

- Palmatier, Robert Allen (1 January 1995). Speaking of Animals: A Dictionary of Animal Metaphors. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29490-7 – via Google Books.

- Grasso, John (2013-06-13). Historical Dictionary of Football. ISBN 978-0-8108-7857-0.

- Howard Liss (1975-09-01). They changed the game: football's great coaches, players, and games. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-397-31628-1.

- McHugh, Roy (1 January 2008). Ruanaidh – The Story of Art Rooney and His Clan. Ruanaidh-Story of Art Rooney. ISBN 978-0-9814760-2-5 – via Google Books.

- Grange, Red; Morton, Ira (1953). The Red Grange Story: An Autobiography. University of Illinois Press. p. 75. ISBN 0252063295.

- Stone, Kevin (November 18, 2015). "Ten things you might not know about Joe Theismann's injury 30 years ago". ESPN.com. ESPN. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- "VIDEO: Patriots score flea-flicker TD against Steelers in NFC (AFC) Championship Game". Business Insider. Business Insider. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Horner, Scott (Jan 21, 2018). "NFL playoffs: Teams go flea-flicker crazy in conference championship games". indystar.com. The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- Lyles Jr., Harry (Jan 21, 2018). "Championship Sunday blessed us with not one, not two, but THREE successful flea flickers". SB Nation. Retrieved 2018-01-22.