First Oil Well in Oklahoma

The First Oil Well in Oklahoma was drilled in 1885 in Atoka County, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory, though it was not completed until 1888.

First Oil Well in Oklahoma | |

| |

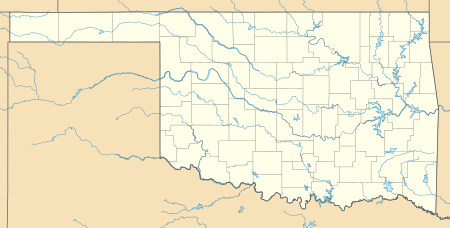

| Nearest city | Wapanucka, Oklahoma |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 34°24′6″N 96°22′25″W |

| Area | 5 acres (2.0 ha) |

| Built | 1888 |

| NRHP reference No. | 72001053[1] |

| Added to NRHP | April 13, 1972 |

The First Oil Well in Oklahoma (also known as Old Faucett Well) is a historic oil well site near the present Wapanucka, Johnston County, Oklahoma. It was drilled by Dr. H.W. Faucett, who started work in 1885 on Choctaw land for the Choctaw Oil and Refining Company, but the 1,414-foot (431 m) well was not completed until 1888. A small amount of oil and gas was produced, but not in commercially usable quantity. The well was abandoned after Faucett fell ill and died later in 1888.[2] The first commercially productive well in Indian Territory was the Nellie Johnstone No. 1 well near Bartlesville, Oklahoma (then in the Cherokee Nation), drilled in 1897.

The well was added to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) in 1972.[1] The capped well casing is the well's only remnant.[2]

Background

The presence of oil in Indian Territory had been observed for many years, usually as natural seepage from the ground. Oklahoma Historian Muriel H. Wright described an incident in 1859, in which Lewis Ross, the brother of Cherokee Chief John Ross, attempted to drill a deep water well for the salt works he owned in the Cherokee Nation. Instead, the well hit an oil formation. She reported that production was estimated at ten barrels a day for nearly a year. Production stopped when gas pressure in the formation dropped too low to continue the flow.[3]

According to the NRHP submission, Dr. H. W. Faucett, a resident of New York, was one of the first businessmen to recognize the potential of oil as a fuel in Indian Territory. He wrote the following letter to Rev. Allen Wright, Governor of the Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory, dated December 12, 1883, proposing terms for exploiting this resource.[2]

... It would be impossible to interest capital in the work unless there was some agreement as to the extent of territory that could be had and the specified royalty; it would not do to wait until petroleum was found. You will please write me fully and explicitly as to what can be done in both the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations. Say if you think the exclusive privilege can be had, also the pipe line privilege for transporting oil.[2]

Allen Wright evidently approved the proposal in principle and passed it on to the tribal council. On October 23, 1883, the council approved creating the "... Choctaw Oil and Refining Company, for the purpose of finding petroleum or rock oil, and increasing the revenue of the Choctaw Nation."[2][lower-alpha 1] The authorizations (basically concessions) gave exclusive rights for producing, transporting and refining in both nations ... an larea of nearly 20,000 square miles (52,000 km2).[2]

Muriel Wright reported that Dr. Eliphalet Nott Wright,[lower-alpha 2] then president of the Choctaw and Refining Company, enthusiastically backed Faucett. On several occasions when funds ran dangerously low, Dr. Wright supplied his own money to pay the workers and keep the well digging work going. This calmed the fears of other important Choctaws that Faucett was at fault for delaying completion of the well.[3]

Drilling operation

Faucett's crew erected a drilling rig on Choctaw land near Clear Boggy Creek in late 1885. The actual drilling operation was a very slow operation because all supplies had to be shipped by railroad from St. Louis to Atoka, then loaded onto oxcarts and driven 14 miles (23 km) to the job site. Poor lines of communications with Faucett's backers in the East slowed the delivery of funds, further hampering progress.[2][3]

Construction of the Choctaw well apparently did not begin until after August 1885. By that time, members of both the Choctaw and Cherokee companies were complaining openly about the delays. Faucett explained to the Choctaw company that everything was ready to begin. However, the Cherokee operation, which had been approved a few months after the Choctaw agreements, would be started later. So, the Cherokee council repealed its 1884 act, effectively canceling their part of the project. On receiving this news, Faucett's New York backers, also backed out of the deal. That forced Faucett to find new financial backing in St. Louis. When Robert L. Owen [lower-alpha 3] tried to get the Cherokee council to reinstate the project in the following year, he found that both the Cherokees and the St. Louis backers had lost interest, so the Cherokee well was never resumed.[3]

End of the Choctaw project

The Choctaw project continued as promised, without unnecessary delays. Finally, the hole reached a depth of 1,414 feet (431 m), when the well started showing both oil and gas.[2] Faucett became ill at the jobsite just as work was being completed. He rushed to his home in Neosho, Missouri to seek medical treatment, but died shortly after. Evidently, all other parties to the project felt they could not continue without him, so the Choctaw Oil Company capped the well, abandoned the site and went out of business.[2][3]

Notes

- Faucett had also contacted the Cherokee Nation with similar arrangement for drilling on its lands. The Cherokee Council approved his proposal on December 13, 1884.[2]

- Dr.E. N. Wright was the son of Rev. Allen Wright (and the uncle of Muriel Wright)[4]

- Robert L. Owen was an influential Cherokee, who became one of Oklahoma's first two U.S. Senators immediately after statehood in 1907.

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Ruth, Kent (August 1971). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form: First Oil Well in Oklahoma". National Park Service. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- Wright, Muriel H. "First Oklahoma Oil was Produced in 1859." Chronicles of Oklahoma. Vol. 4, No. 4. December, 1926. Accessed August 18, 2016.

- Wright, Muriel H. "A Brief Review of the Life of Doctor Eliphalet Nott Wright (1858-1932)." Chronicles of Oklahoma. Vol. 10, No. 2, June 1932.] Accessed August 19, 2016