First Church and Parish in Dedham

The First Church and Parish in Dedham is a Unitarian Universalist congregation in Dedham, Massachusetts. It was the 14th church established in Massachusetts.[1] The current minister, Rev. Rali M. Weaver, was called in March 2007, settled in July, and is the first female minister to this congregation.

| Part of a series on |

| Dedham, Massachusetts |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

|

| Places |

| Organizations |

| Businesses |

| Education |

History

Establishment

Dedham was first settled in 1635 and incorporated in 1636. While it was of the utmost importance for the founders, "founding a church was more difficult than founding a town."[2] Meetings were held late in 1637 and were open to "all the inhabitants who affected church communion... lovingly to discourse and consult together [on] such questions as might further tend to establish a peaceable and comfortable civil society ad prepare for spiritual communion."[3] On the fifth day of every week they would meet in a different home and would discuss any issues "as he felt the need, all 'humbly and with a teachable heart not with any mind of cavilling or contradicting.'"[3][4][5]

After they became acquainted with one another, they asked if "they, as a collection of Christian strangers in the wilderness, have any right to assemble with the intention of establishing a church?"[6] Their understanding of the Bible led them to believe that they did, and so they continued to establish a church based on Christian love, but also one that had requirements for membership. In order to achieve a "further union", they determined the church must "convey unto us all the ordinances of Christ's instituted worship, both because it is the command of God... and because the spiritual condition of every Christian is such as stand in need of all instituted ordinances for the repair of the spirit."[6] The group would meet for worship under a large tree in the forest, believed to be near the site of the current church.[5][lower-alpha 1]

It took months of discussions before a church covenant could be agreed upon and drafted.[3] The group established thirteen principles, written in a question and answer format, that established the doctrine of the church.[8] In the summer of 1638, Allen, by common consent, was asked to organize a church and chose Wheelock as his assistant.[9] With the doctrinal base was agreed upon, 10 men were selected to seek out the "living stones" upon which the congregation would be based.[10]

The group began to meet separately and, one by one, beginning with Allen, they would leave the room so that the others could elect or reject them.[10][9] They decided that six of their own number--John Allen, Ralph Wheelock, John Luson, John Fray, Eleazer Lusher, and Robert Hinsdale—were suitable to form the church.[10][9][lower-alpha 2] John Hunting, who was new to the town, was also deemed acceptable.[10][9] One of the original 10, Edward Alleyn, was considered a borderline case, but the questions about him were satisfactory addressed and he was approved.[11][9] The eight men submitted themselves to a conference of the entire community.[10][9]

The group sent letters to other churches and to magistrates informing them of their intention to form a church.[12] The Great and General Court responded by saying that no church should be gathered without the advice of other churches and the consent of the government.[12] As they did not believe they needed the approval of any outside body to gather a church, they wrote to the governor seeking an explanation.[12] He confirmed that there was no intent to adbridge their liberties and that gathering a church in the manner they proposed was not unlawful.[12]

Finally, on November 8, 1638, two years after the incorporation of the town and one year after the first church meetings were held, the covenant was signed and the church was gathered.[13][4][14] Guests from other towns were invited for the event as they sought the "advice and counsel of the churches" and the "countenance and encouragement of the magistrates."[13][4]

At the first service, Wheelock began with a prayer and then Allen spoke to the assembly.[12] Each of the eight members then made a public profession of faith.[12] Allen then asked the invited church elders to confer and address the congregation on what they had observed.[12] Rev. Mr. Mathers of Dorchester then spoke to say that they saw nothing objectionable and closed with "a most loving exhortation."[12] The church elders then extended the right hand of fellowship to the new congregation.[12]

Early years

On the Sunday after Allen's ordination, he informed the congregation that any children of church members who had not yet been baptized could receive it on the following Sunday.[15] John and Hannah Dwight brought their daughters, Mary and Sarah, and they became the first people to be baptized in the church.[15] Communion was distributed on the Sunday after that.[15]

Widows who cared for the meetinghouse were church officers.[1] Deacons began being elected in 1650 with Henry Chickering and Nathan Aldus were the first men elected to the role.[1] Their role was to sing psalms and to hold the collection boxes as congregants filed before them to drop in money for the poor.[16] The magistrates and "chief gentleman" went first, followed by the elders and male members of the congregation.[1] Then came single people, widows, and women without their husbands.[1]

Though Allen's salary was donated freely by members and non-members alike his salary was never in arrears, showing the esteem in which the other members of the community held him.[17] In the 1670s, as the Utopian spirit of the community waned, it became necessary to impose a tax to ensure the minister was paid.[18]

In 1763, the second and current meetinghouse was constructed.[19] It was renovated and reoriented to face the Little Common in 1820.[19] In the church, a portrait of Alvan Lamson is to the left of the pulpet and one of Joseph Belcher hangs to the right.[19]

Prior to Jason Haven becoming minister, the church had very infrequently enforced a provision requiring anyone who had sex before marriage to confess the sin before the entire congregation.[20] The first records of such confessions took place during the pastorate of Samuel Dexter, and they were rare.[20] Such confessions increased dramatically during Haven's term, however.[21] During his first 25 years there were 25 such confessions, of which 14 came during the years 1771 to 1781.[21] In 1781, he preached a sermon condemning fornication and the then-common practice of women sleeping with men who professed their intention to marry.[21] The sermon was so long and memorable that decades later, in 1827, congregants still remembered the ashamed looks on the faces of those gathered and how uncomfortable many were.[21]

Membership

At first, only 'visible saints' were pure enough to become members.[4][22] A public confession of faith was required, as was a life of holiness.[23][4] A group of the most pious men interviewed all who sought admission to the church.[4] All others would be required to attend the sermons at the meeting house, but could not join the church, nor receive communion, be baptized, or become an officer of the church.[23]

Once the church was established, residents would gather several times a week to hear sermons and lectures in practical piety.[2] By 1648, 70% of the men and many of their wives, and in some cases the wives only, had become members of the Church.[24][4] Between the years of 1644 and 1653, 80% of children born in town were baptized, indicating that at least one parent was a member of the church. Servants and masters, young and old, rich and poor alike all joined the church.[24] Non-members were not discriminated against as seen by several men being elected Selectmen before they were accepted as members of the church.[25]

While in early years nearly every resident of the town was a member of the church,[24] membership gradually slowed until only eight new members were admitted from 1653 to 1657.[26] None joined between 1657 and 1662.[26] By 1663, nearly half the men in town were not members, and this number grew as more second generation Dedhamites came of age.[27] The decline was so apparent across the colony by 1660 that a future could be seen when a minority of residents were members,[28] as happened in Dedham by 1670[29] It was worried that the third generation, if they were born without a single parent who was a member, could not even be baptized.[26] The number of infant baptisms in the church fell by half during this period, from 80% to 40%.[27]

To resolve the problem, an assembly of ministers from throughout Massachusetts endorsed a "half-way covenant" in 1657 and then again at a church synod in 1662.[28] It allowed parents who were baptized but not members of the church to present their own children for baptism; however, they were denied the other privileges of church membership, including communion.[28][27] Allen endorsed the measure but the congregation rejected it, striving for a pure church of saints.[27]

Initially, a public profession of faith was officially required to join the church, though in practice it was not always enforced.[15] By 1742 a person might, at their own discretion, make either a public profession or a private one to the minister to gain admittance.[15] By 1793, the minister would propose a new member and, if no objection was raised within two weeks, they would be admitted.[15]

Women could be members of the church but could not vote in the church meeting.[30]

Covenants

The first covenant was signed the day the church was gathered, November 8, 1638.[13][4][14] New covenants were later adopted on May 23, 1683, March 4, 1742, in 1767, and on April 11, 1793.[14]

The 1793 covenant was much broader than those that preceded it.[20][31][32] Jason Haven, the minister at the time, expressed the prevailing belief in the church that all should be permitted to "enjoy the right of his private opinion provided he doth not break in upon the rights of others."[32] The new covenant allowed anyone who declared himself to be a Christian to be admitted as a member.[20]

We profess our belief in the Christian Religion. We unite ourselves together for the purpose of obeying the precepts and honoring the institutions of the religion which we profess. We covenant and agree with each other to live together as a band of Christian brethren; to give and receive counsel and reproof with meekness and candor; to submit with a Christian temper to the discipline which the Gospel authorizes the church to administer; and diligently to seek after the will of God, and carefully endeavor to obey all His commandments.[31]

Dissent and division of the church

As the town grew and residents began moving to outlying areas, the town was divided into parishes and precincts.[33] Parishes could hire their own ministers and teachers while precincts could do that and elect their own tax assessors and militia officers.[34]

In 1717, the Town Meeting voted, in what was the first ever concession to outlying areas, to exempt residents from paying the minister's salary if they lived more than five miles from the meetinghouse.[35] Those who chose to do so could begin attending another church in another town.[35] In May 1721, Town Meeting refused to allow an outlying section of town to hire their own minister, prompting that group to seek to break away as the town of Walpole.[35]

The Clapboard Trees section of town had more liberal religious views than did those in either the original village or South Dedham.[36][37] After a deadlocked Town Meeting could not resolve the squabbling between the various parts of town, the General Court first put them in the second precinct with South Dedham, and then in the first precinct with the village.[36] This did not satisfy many of them, however, and in 1735 they hired their own minister along with some likeminded residents of the village.[36] This was an act of dubious legality and the General Court once again stepped in, this time to grant them status as the third precinct and, with it, the right to establish their own church.[36][37] The General Court also allowed more liberal minded members of conservative churches to attend the more liberal churches in town, and to apply their taxes to pay for them.[37]

Split with the Allin Congregational Church

The preaching of Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield helped to revive the churches of Dedham during the Great Awakening.[38] The theological debates that arose as a result, however, helped bring about a split in the churches into different denominations.[38]

In the early 19th century, all Massachusetts towns were Constitutionally required to tax their citizens "for the institution of the public worship of God, and for the support and maintenance of public Protestant teachers of piety."[39] All residents of a town were assessed, as members of the parish, whether or not they were also members of the church. The "previous and long standing practice [was to have] the church vote for the minister and the parish sanction this vote."[40]

In 1818 "Dedham [claimed] rights distinct from the church and against the vote of the church."[40] The town, as the parish, selected a liberal Unitarian minister, Rev. Alvan Lamson, to serve the First Church in Dedham.[41] The members of the church were more traditional and rejected Lamson by a vote of 18-14.[41] When the parish installed and ordained Lamson, the more conservative or orthodox members left in 1818 decided to form a new church nearby, what is now known as the Allin Congregational Church.[41][lower-alpha 3] The departing members included Deacon Samuel Fales, who took parish records, funds, and the valuable silver used for communion with him.[42][43][41]

The case reached the Supreme Judicial Court who ruled that "[w]hatever the usage in settling ministers, the Bill of Rights of 1780 secures to towns, not to churches, the right to elect the minister, in the last resort."[44] The court held that the property had to be returned to First Church, setting a precedent for future congregational splits that would arise as Unitarianism grew.[42] The case was a major milestone in the road towards the separation of church and state and led to the Commonwealth formally disestablishing the Congregational Church in 1833.[45] The orthodox faction supposedly responded to the decision with the saying, "They kept the furniture, but we kept the faith."[42]

Despite the court ruling, the silver was not returned to First Church.[46] It remained hidden away until 1969 when it was donated to the Dedham Historical Society as a neutral third party.[46] Today it is on permanent loan to the Museum of Fine Arts, and replicas have been made for both churches.[47]

Ministers

| Minister | Years of service | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| John Allen | 1639-1671 | [48][49][50][51][52] |

| Vacant | 1671-1673 | |

| William Adams | December 3, 1673 – August 17, 1686 | [48][53][54] |

| Vacant | 1685-1693 | [54][55] |

| Joseph Belcher | November 29, 1693 – April 27, 1723 | [56][57][48][54][lower-alpha 4] |

| Samuel Dexter | May 6, 1724 – January 29, 1755 | [48][54][58][54] |

| Jason Haven | February 5, 1756 – May 17, 1803 | [48][20] |

| Joshua Bates | March 16, 1803-February 20-1818 | [59][48] |

| Alvan Lamson | October 29, 1818 – October 29, 1860 | [48][60][61] |

| Benjamin H. Bailey | March 14, 1861 – October 13, 1867 | [48][62] |

| George McKean Folsom | March 31, 1869 – July 1, 1875 | [48] |

| Seth Curtis Beach | December 29, 1875- | [48][63] |

| William H. Fish, Jr. | [63] | |

| J. Worsley Austin | October 15, 1898- | [63][64] |

| Roger S. Forbes | [63] | |

| William H. Parker | [63] | |

| Charles R. Joy | [63] | |

| Lyman V. Rutledge | [63] | |

| Rali Weaver | 2007–present | [65] |

John Allen

A "tender" search for the flock's first minister took several months, but finally John Allen was ordained as pastor and John Hunting as Ruling Elder.[66][67] The selection process was not easy.[49] John Phillips, though he was "respected and learned"[29] and much desired, twice refused calls to become minister.[29][68][49] Thomas Carter likewise declined the post and instead became minister in Woburn.[49]

The "gifts and graces" of each member of the church was tested and considered for nearly two years before they settled upon Allen.[49] Then came the question of whether he should be called minister or pastor or something else.[49] The opinion of other churches was requested, but they replied with indifference.[49] Allen became known as pastor.[49] As he held the teaching office, his role was to pray, preach, and instruct.[49] As pastor, he was to administer baptism and other sacraments.[49]

After selecting a pastor, the names of Ralph Wheelock, John Hunting, Thomas Carter, and John Kingsbury were put forward for the role of ruling elder with Hunting eventually being selected.[49] On April 24, 1639, a day of fasting and prayer, Hunting and Allen were ordained in the presence of the Dedham congregation and the elders of other churches.[49] The hands of Allen, Wheelock, and Edward Allyne were laid upon Hunting during his ordination and those of Hunting, Wheelock, and Allyne were laid upon Allen for his ordination.[15]

As in England, Puritan ministers in the American colonies were usually appointed to the pulpits for life[69] and Allen served for 32 years.[51] He received a salary of between 60 and 80 pounds a year.[17] Though laws of the colony required churches to provide homes for their ministers, Dedham did not.[70] When land was divided, Allen's name was always at the top of the list and he received the largest plot.[17][70] Towards the end of his life in 1671, Allen's health deteriorated and it became necessary to hire visiting ministers.[52]

William Adams

After Allen's death the pulpit went without a settled minister for a long stretch[71] but he was eventually succeeded by William Adams.[57][72] He was the congregation's first choice, but he declined their first two calls.[72] In September 1672 he agreed to preach on a trial basis and, on December 3, 1673 he was ordained.[73][72] He served until his death in 1685.[73][72]

Joseph Belcher

The church was without a minister from 1685 to 1692.[55] It is assumed that several young men were offered the pulpit but declined it during those years.[55] At the end of 1691 the congregation voted to accept the half-way covenant and a new minister was found and installed the next year.[74]

That minister, Joseph Belcher, began preaching in the spring of 1692 and was installed on November 29, 1693.[56][57] He first preached in Dedham on April 17, 1692 and then again for the second time a month later on May 15.[75] The records of May 23, 1692 Town Meeting indicate that "the Ch and Town have given a call" to have Belcher move to Dedham and serve as the minister.[75] Belcher returned to preach on June 12 and did so regularly beginning on October 30.[75] Church records indicate the call was given on December 4, 1692.[75] A few weeks later, on December 23, Town Meeting voted to set his salary at 60 pounds a year.[75]

Belcher was minister at First Church from 1693[54][56][57] until his death in 1723,[54] although illness prevented him from preaching after 1721.[56] During his time as minister, a tax was instituted in Dedham to ensure his salary was paid.[57][76] He tried to have the church return to a system of voluntary contributions in 1696, but it failed.[77][76] By the end of his tenure his salary was 100 pounds a year plus the firewood provided by members of the parish.[76] The town also contributed 60 pounds to build a parsonage on land now owned by the Allin Congregational Church.[76]

Five of his sermons survive.[76] One was delivered before the Great and General Court, one before the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company, two preached in Dedham specifically for young people, and one at the ordination of Nathaniel Cotton in Bristol, Rhode Island.[76] His portrait, donated in 1839, hangs just left of First Church's pulpit.[78]

Samuel Dexter

Samuel Dexter preached for the first time on October 15, 1722 and was called to minister at First Church in the fall of 1723.[79] His call was opposed by some in the community, but it was for primarily political reasons, not necessarily theological ones.[58] He was ordained on May 6, 1724 and served until his death in 1755.[79]

During his ministry, several outlying areas of Dedham began to establish their own churches.[79] It was then that the church, which previously had been known as the Church of Christ, began to be called First Church in Dedham.[79] After the churches split his ministry was "calm and quiet," but before he did there were members of the community, whom he called "certain sons of ignorance and pride," who insulted him to his face.[79] Meetings were frequently called to correct the behavior of disorderly members and this led to an ecclesiastical council in July 1725.[79]

Jason Haven

Jason Haven was called to the Dedham church in 1755 and ordained on February 5, 1756.[80][81] As part of the call, he was offered 133 pounds, six shillings, and 8 pence in addition to an annual salary of 66 pounds, 13 shillings, and 8 pence plus 20 cords of wood.[31] He was also granted "the use and improvement" of plot of land near the meetinghouse and given three parcels of land in Medfield, Massachusetts.[31] There was some opposition to his call but, after 40 years of ministry, he counted those early opponents as friends.[31]

As minister, he brought a number of young men into his household to prepare for college or the ministry; 14 of them went to Harvard College.[31] He also oversaw the construction of the current meetinghouse in 1762.[31] A gifted orator, he was frequently called upon to preach at ordinations and to address public assemblies.[21][82] He addressed the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company at the election of their officers in 1761[21][83] and preached a sermon before the Great and General Court in 1769.[83] He preached the general election sermon in 1766 and the Dudleian lecture in 1789.[21] In 1794, he preached the convention sermon.[21]

In 1793, he instituted a new method for bringing new members into the congregation.[20] The minister would propose an individual and, if there was no objection after 14 days, they became a member of the church.[20]

Joshua Bates

After Haven's death, an effort was made to limit the term of the minister rather than granting him a life tenure.[32] The next occupant of the pulpit, from 1803 to 1818, was Joshua Bates.[59][84] He was first called to be the associate pastor with Jason Haven in 1802 and was ordained on March 16, 1803 "before a very crowded, but a remarkably civil and brilliant assembly."[83] Three months later, Haven died.[83] There were some who opposed his call, but Fisher Ames made an eloquent speech of support and this was enough to issue a call.[83] Several members, including Fisher Ames' brotherNathaniel, left the church, however, and became Episcopalians.[83]

During his pastorate, the Lord's Supper was administered every six weeks.[85] On the Thursdays preceding, he would preach the Preparatory Lecture.[85] Students in the nearby school were marched to the meetinghouse to listen to the lecture, and Bates would visit the school on Mondays to quiz students on the catechism.[85]

Politically, he was an ardent Federalist while the town and the church were strongly anti-Federalist.[85][86] His sermons often were intolerant of those whose politics who differed from his own.[85][86] He believed Thomas Jefferson to be an infidel and that Jefferson's followers, including those in Dedham were at best doubtful Christians.[85][86] Bates also gradually withdrew from allowing guest ministers to preach, a common and popular practice at the time.[87] The more orthodox members of the church believed it to be supporting heresy when ministers who leaned Unitarian were invited to preach.[88]

The anti-Federalist members of the congregation didn't like paying taxes to support hear Federalist sermons, and the liberal parishioners didn't like the exclusion of other voices from the pulpit.[86] In 1818, Bates asked to be dismissed from the church to accept the presidency of Middlebury College.[85] It is assumed that many in the congregation were glad to let him go.[85][86] His last sermon was delivered on February 15, 1818.[89] Bates went on to become Chaplain of the United States House of Representatives.

Alvan Lamson

Lamson's appointment as minister came shortly after he was graduated from Harvard College and three months after the resignation of Bates.[90] On August 31, 1818, at a meeting of the parish, or the inhabitants of the town who were taxed to pay the minister's salary, Lamson was elected by an 81-44 majority.[90] He beat out two other candidates.[90] Members of the church opposed his election by a vote of 18-14, with six members not voting.[90] Those who opposed Lamson did not raise any objections to his moral or professional qualifications.[90]

After Lamson accepted the parish's call without the concurrence of the church, a council of pastors and delegates from 13 other churches was convened on October 28, 1818.[90] After two days of hearings and deliberations, it prepared a report in favor of Lamson's ordination.[61] Lamson was ordained by Rev. Henry Ware.[91]

His ordination by Rev. Henry Ware.[91] led to the case of Baker v. Fales and the split of the church into First Church and the Allin Congregational Church.

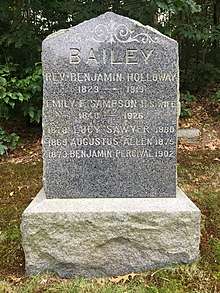

Benjamin H. Bailey

Benjamin H. Bailey served at First Church from 1861 to 1867.[63][62] In Dedham, he presided over the funeral of his predecessor, Alvan Lamson[92] and led the service at the 250th anniversary of the church's gathering in 1888 where he delivered an historical discourse.[93]

In 1867, he was called to Portland, Maine.[62]

Notes

- Some records have the site as being closer to Dwight's Brook, near the home of John Dwight.[7]

- Joseph Kingsbury and Thomas Morse, members of the original ten, agreed at the end of the discussions to suspend their candidacies for the time being.[10]

- The new church was named from John Allen, the original pastor of First Church.

- Belcher preached until 1721 when illness prevented him from doing so any further.[56]

References

- Smith 1936, p. 66.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 24.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 25.

- Brown & Tager 2000, p. 38.

- Smith 1936, p. 60.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 26.

- Smith 1936, pp. 60-61.

- Lockridge 1985, pp. 25-26.

- Smith 1936, p. 61.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 28.

- Lockridge 1985, pp. 28-29.

- Smith 1936, p. 63.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 29.

- Smith 1936, p. 62.

- Smith 1936, p. 65.

- Smith 1936, pp. 65-66.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 32.

- Lockridge 1985, pp. 85-87.

- Dedham Historical Society 2001, p. 26.

- Worthington 1827, p. 108.

- Worthington 1827, p. 109.

- Lockridge 1985, pp. 26-27.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 27.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 31.

- Lockridge 1985, pp. 31-32.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 33.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 34.

- Brown & Tager 2000, p. 39.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 80.

- Wright 1988, p. 23.

- Smith 1936, p. 76.

- Wright 1988, p. 18.

- Lockridge 1985, pp. 97-102.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 102.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 108.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 115.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 118.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 162.

- "Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts". Wikisource.com. 1780. Retrieved 2006-11-28. See Part the First, Article III.

- Ronald Golini. "Taxation for Religion in Early Massachusetts". www.rongolini.com. Archived from the original on 2007-01-08. Retrieved 2006-11-28.

- Sally Burt (2006). "First Church Papers Inventoried". Dedham Historical Society Newsletter (January). Archived from the original on December 31, 2006.

- Robinson 1985, p. 37.

- "UUA, United Church of Christ 'just friends,' say leaders". UU World Magazine. 2006-11-03. Retrieved 2019-07-24.

- Eliphalet Baker and Another v. Samuel Fales, 16 Mass. 403

- Johann N. Neem (2003). "Politics and the Origins of the Nonprofit Corporation in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, 1780-1820". Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 32 (3): 363. doi:10.1177/0899764003254593.

- "375 Years of History in Short". First Church and Parish in Dedham. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- Dedham Historical Society 2001, p. 28.

- Beach 1878, p. 27.

- Smith 1936, p. 64.

- Worthington 1827, p. 101.

- Abbott 1903, pp. 290-297.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 85.

- Worthington 1827, p. 104.

- Worthington 1827, p. 105.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 35.

- Bartlett, J. Gardner (1906). The Belcher families in New England. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 86.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 109.

- Worthington 1827, p. 110.

- Worthington 1827, p. 112.

- Smith 1936, p. 82.

- The Unitarian Register. American Unitarian association. 1919. p. 670. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Smith 1936, p. 87.

- Cuckson, John (1898). The place of religion in life. a sermon preached at the installation of the Rev. J. Worsley Austin, M.A., as pastor of the First Church in Dedham. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- "Rali Weaver". LinkedIn. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- "A Capsule History of Dedham". Dedham Historical Society. 2006. Archived from the original on October 6, 2006. Retrieved November 10, 2006.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 30.

- Tuttle 1915, p. 211.

- Friedman, Benjamin M. (2005). The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 45.

- Smith 1936, p. 69.

- Lockridge 1985, p. 87.

- Smith 1936, pp. 70-71.

- Caulkins, Frances Manwaring (1849). Memoir of the Rev. William Adams, of Dedham, Mass. : and of the Rev. Eliphalet Adams, of New London, Conn. Cambridge Massachusetts: Metcalf and Company. p. 22.

- Lockridge 1985, pp. 35-36.

- Smith 1936, p. 72.

- Smith 1936, p. 73.

- Lockridge 1985, pp. 96-97.

- Smith 1936, pp. 73-74.

- Smith 1936, p. 74.

- Smith 1936, p. 75.

- Allen 1832, p. 443.

- Smith 1936, pp. 76-77.

- Smith 1936, p. 77.

- Smith 1936, pp. 77-80.

- Smith 1936, p. 78.

- Wright 1988, p. 22.

- Wright 1988, pp. 20-21.

- Wright 1988, p. 20.

- Wright 1988, p. 16.

- Smith 1936, p. 81.

- Wright 1988, p. 27.

- The New England Historical and Genealogical Register. New England Historic-Genealogical Society. 1865. p. 91. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- First Parish, Dedham, Mass; First Congregational Church (Dedham, Mass.) (1888). Commemorative Services at the Two Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary of the Gathering of the First Church in Dedham, Mass: Observed November 18 and 19, 1888. Joint committee of the two churches. pp. 112–.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Works cited

- Dedham Historical Society (2001). Dedham. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-0944-0. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- Lockridge, Kenneth (1985). A New England Town. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-95459-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Worthington, Erastus (1827). The history of Dedham: from the beginning of its settlement, in September 1635, to May 1827. Dutton and Wentworth. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- Smith, Frank (1936). A History of Dedham, Massachusetts. Transcript Press, Incorporated. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- Robinson, David (1985). The Unitarians and the Universalists. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313248931.

- Allen, William (1832). An American biographical and historical dictionary...: containing an account of the lives, characters, and writings of the most eminent persons in North America from its first settlement, and a summary of the history of the several colonies and of the United States. W. Hyde. p. 443. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Wright, Conrad (1988). "The Dedham Case Revisited". Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society. 3. Massachusetts Historical Society. 100: 15–39. JSTOR 25080991.

- Tuttle, Julius H. (1915). "A pioneer in the public service of the church and of the college". Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts. The Colonial Society of Massachusetts. 17. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- Beach, Seth C.; Carroll, Sanford; Smith, Nathaniel; Whitney, Mrs. S.W.; Maynard, Mrs. C.E.; Capen, Charles James (1878). Covenant of the First Church in Dedham: With Some Facts of History and Illustrations of Doctrine; for the Use of the Church. H. H. McQuillen. Retrieved 30 October 2019.