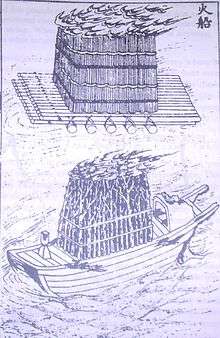

Fire ship

A fire ship or fireship, used in the days of wooden rowed or sailing ships, was a ship filled with combustibles, or gunpowder deliberately set on fire and steered (or, when possible, allowed to drift) into an enemy fleet, in order to destroy ships, or to create panic and make the enemy break formation.[1] Ships used as fire ships were either warships whose munitions were fully spent in battle, surplus ones which were old and worn out, or inexpensive purpose-built vessels rigged to be set afire, steered toward targets, and abandoned quickly by the crew.

Explosion ships or 'hellburners' were a variation on the fire ship, intended to cause damage by blowing up in proximity to enemy ships.

Fireships were used to great effect by the outgunned English fleet against the Spanish Armada during the Battle of Gravelines,[2] the Dutch Raid on the Medway and by the Greeks in the Greek War of Independence.

History

Ancient era, first uses

Possibly the oldest account of the military use of a fire ship is recorded by the Greek historian Thucydides on the occasion of the failed Athenian Sicilian Expedition (415–413 BC).[3] In the episode, the Athenian expeditionary force successfully repels an attack by the Syracusans:

The rest [of the Athenian force] the enemy tried to burn by means of an old merchantman which they filled with faggots and pine-wood, set on fire and let drift down the wind which blew full on the Athenians. The Athenians, however, alarmed for their ships, contrived means for stopping it and putting it out, and checking the flames and the nearer approach of the merchantman, thus escaped the danger.

A fire ship was used in the Battle of Red Cliffs (208) on the Yangtze River when Huang Gai assaulted Cao Cao's naval forces with a fire ship filled with bundles of kindling, dry reeds, and fatty oil.

Fire ships were decisively employed by the Vandals against the armada sent by the Eastern Roman Empire, in the Battle of Cape Bon (468).

The invention of Greek fire in 673 increased the use of fire ships, at first by the Greeks and afterward by other nations as they came into possession of the secret of manufacturing this substance. In 951 and again in 953 Russian fleets narrowly escaped destruction by fire ships.

Age of fighting sail, refinement

While fire ships were used in the Medieval period, notably during the crusades, these were typically ships that were set up with combustibles on an adhoc basis. The career of the modern fire ship, as a naval vessel type designed for this particular function and made a permanent addition to a fleet, roughly parallels the era of cannon-armed sailing ships, beginning with the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 and lasting until the Allied victory over the Turks at the Battle of Navarino in 1827. The first modern fireships were put to use in early 17th century Dutch and Spanish fleet actions during the Thirty Years War. Their use increased throughout that century, with purpose-built fireships a permanent part of many naval fleets, ready to be deployed whenever necessary. Initially small and often obsolete smaller warships were chosen as fireships but by 1700 fireships were being purpose-built with specific features for their role. Most were adaptations of the usual small warships of the day – brigs or ship-rigged sloops-of-war with between 10 and 16 guns. The practical design features of purpose-built fireships included a lattice-work false deck below the planks of the main deck – the planks would be removed and the combustibles and explosives stacked on the lattice, which gave good draught and ensured the fire would hold and spread. A number of square-section chimneys would be let into the forecastle and quarterdeck to also help ensure a good draught for the fire. The gunports would be hinged at the bottom (rather than the top as on other warships) so that they would be kept open by gravity rather than ropes (which would otherwise burn thorough), further ensuring a good air supply. On the other hand, the lower parts of the masts would be surrounded by 'coffer dams' to ensure that the fire would not bring down the masts prematurely and thus deprive the fireship of motive power. Grappling hooks would be fitted to the ends of the yardarms so that the fireship would become entangled in its target's rigging. A large sally-port door was let into the rear quarter of the ship (usually the starboard side) to allow easy exit for the crew once the fire had been set and lit. There was often a chain fixed here for mooring the escape boat rather than a rope that may have been damaged by the fire. Because fireships were used relatively rarely and only in specific tactical conditions even in their heyday, and there was always demand for small cruisers and warships, most purpose-built 'fireships' served long careers as ordinary warships without ever being used for their actual purpose. Of the five fireships used in Holmes's Bonfire of 1666 three had been in service with the Royal Navy for over a decade before being deployed on their final mission.

While only used sparingly during the Napoleonic Wars, fire ships as a distinct class were part of the British Royal Navy until 1808, at which point the use of permanently designated fire ships attached to British squadrons disappeared.[4] Fire ships continued to be used, sometimes to great effect, such as by the U.S. Navy at the Battle of Tripoli Harbor in 1804 and by the British Navy's Thomas Cochrane at the Battle of the Basque Roads in 1809, but for the most part they were considered an obsolete weapon by the early 19th century.

Warships of the age of sail were highly vulnerable to fire. Made of wood, with seams caulked with tar, ropes greased with fat, and stores of gunpowder, there was little that would not burn. Accidental fires destroyed many ships, so fire ships presented a terrifying threat. With the wind in exactly the right direction a fire ship could be cast loose and allowed to drift onto its target, but in most battles fire ships were equipped with skeleton crews to steer the ship to the target (the crew were expected to abandon ship at the last moment and escape in the ship's boat). Fire ships were most devastating against fleets which were at anchor or otherwise restricted in movement. At sea, a well-handled ship could evade a fire ship and disable it with cannon fire. Other tactics were to fire at the ship's boats and other vessels in the vicinity, so that the crew could not escape and therefore might decide not to ignite the ship, or to wait until the fire ship had been abandoned and then tow it aside with small maneuverable vessels such as galleys.

The role of incendiary vessels changed throughout the age of the modern fire ship. The systematic use of fire ships as part of naval actions peaked around the Third Anglo-Dutch War. Whereas just twenty years before a naval fleet might have six to seven fire ships, by the Battle of Solebay in 1672 both the Dutch and English fleets employed typically between 20 and 30 fire ships, and sometimes more.[5] By this time, however, admirals and captains had become very experienced with the limitations of fire ship attacks and had learned how to avoid them during battle. Great numbers of fire ships were expended during the Third Dutch War without destroying enemy men-of-war, and fire ships had become a way to harass and annoy the enemy, rather than destroy him.[6] The successful use of fire ships at the Battle of La Hogue and Cherbourg in 1692 marked both the greatest achievement of a fire ship attack since the Spanish Armada, and also the last significant success for fire ships. Though fire ships as a specified class sailed with the British Royal Navy for another century, they would never have a significant impact on a naval victory. Once the most feared weapons in naval arsenals, fire ships had declined in both importance and numbers, so that by the mid-18th century only five to six British fire ships would be at sea at a time, and the Royal Navy attempted only four attacks using modern fire ships between 1697 and 1800.[7] Hastily outfitted ad hoc fire ships continued to be used in naval warfare; for example, a large number of fire rafts were used in mostly ineffective attacks on the British fleet by American forces during the American Revolution at Philadelphia, on the Hudson River, and elsewhere. The end of the modern fire ship came in the early 19th century, when the British began to use hastily outfitted fire ships at engagements such as Boulogne and Dunkirk despite the presence of purpose-built fire ships in the fleet. The last modern fire ship in the British Royal Navy was Thais, the only designated fire ship out of the entire navy of 638 warships when she was converted to a ship sloop in 1808.[8]

Use in the Greek War of Independence

In the Greek War of Independence, 1821–1832, the extensive use of fire ships by the Greeks allowed them to counterbalance the Turkish naval superiority in terms of ship size and artillery power.[9] As the small fire ships were much more maneuverable than enemy ships of the line, especially in the coasts of the Aegean Sea where the islands, islets, reefs, gulfs and straits restrained big ships from being easily moved, they were a serious danger for the ships of the Turkish fleet. Many naval battles of the Greek war of independence were won by the use of fire ships. The successful use of fireships required the use of the element of surprise (a visible similarity with modern-day naval special operations). It is considered an important landmark in Greek naval tradition.

19th and 20th centuries, obsolescence

From the beginning of the 19th century, steam propulsion and the use of iron, rather than wood, in shipbuilding gradually came into use, making fire ships less of a threat.

During the American Civil War, the Confederate States Navy occasionally used fire rafts on the Mississippi River. These were flatboats loaded with flammable materials such as pine knots and rosin.[10] The fire rafts were set alight and either loosed to drift on the river's current towards the enemy (for example at the Battle of the Head of Passes)[10] or else pushed against Union ships by tugboats (as at the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip).[11]

During World War II in September 1940, there was a British sortie codenamed Operation Lucid to send old oil tankers into French ports to destroy barges intended for the planned invasion of Britain; it was abandoned when both tankers broke down.[12] Ships or boats packed with explosives could still be effective. Such a case was Operation Chariot of 1942, in which the old destroyer HMS Campbeltown was packed with explosives and rammed into the dry dock at Saint-Nazaire, France, to deny its use to the battleship Tirpitz, which could not drydock anywhere else on the French west coast. In the Mediterranean, the Italian Navy made good use of high-speed boats filled with explosives, mostly against moored targets. Each boat, called by the Italians MTM (Motoscafo da Turismo Modificato), carried 300 kilograms (660 lb) of explosive charge inside its bow. Their best-known action was the 1941 assault on Souda Bay, which resulted in the destruction of cruiser HMS York and the Norwegian tanker Pericles, of 8,300 tons.[13][14]

The successful attack by Yemeni insurgents in a speedboat packed with explosives on the guided missile destroyer USS Cole in 2000 could be described as an extension of the idea of a fireship. Another explosive ship attack took place in April 2004, during the Iraq War, when three motor craft laden with explosives attempted the bombing of Khawr Al Amaya Oil Terminal in the Persian Gulf. In an apparent suicide bombing, one blew up and sank a rigid inflatable boat from USS Firebolt as it pulled up alongside, killing two US Navy personnel and one member of the US Coast Guard.[15]

Notable uses

Notable fire ship attacks include:

- Alexander the Great's Siege of Tyre in 332 BC. The Tyrians used the fire ship in attempt to destroy Alexander's mole.[16]

- Syracuse in their battle with the Athenian fleet.

- Geiseric used fire ships in great effect during the Battle of Cap Bon (468).

- Huang Gai's attack on Cao Cao at the Battle of Red Cliffs, 208.

- Battle of San Juan de Ulúa in 1568. John Hawkins' flagship Jesus of Lübeck was attacked by a fire ship before being stormed by Spanish seamen

- Siege of Antwerp in 1585. Both fire ships and exploding vessels were employed together for the first time.

- Francis Drake's attack on the Spanish Armada moored at Gravelines in 1588. The fire ships did no damage, but the Spanish scattered in panic and were easy prey for English ships.[2]

- Maarten Tromp's attack on the Spanish fleet moored off the Kent coast in the Battle of the Downs in 1639. The Spanish fleet was destroyed.

- A joint attack from the Swedish and Dutch fleets against the Danish fleet at the Battle of Fehmarn (1644). Two Swedish fire ships were used (Lilla Delfin and Meerman) and one Danish capital ship exploded. The battle was a decisive Swedish and Dutch victory.

- The 1667 Dutch Raid on the Medway, with 12 available fireships (8 actually used).

- Michiel de Ruyter's attack on the anchored English fleet at the battle of Solebay in 1672 in which HMS Royal James was burned, killing Vice-Admiral Edward Montagu, 1st Earl of Sandwich, and wounding Royal James's captain, Richard Haddock.[17]

- The destruction of 15 French ships of the line, including Soleil Royal, Admirable and Triomphant, in 1692, after the Battle of La Hougue.[18]

- US attack on Tripoli during the First Barbary War in 1804 by USS Intrepid.

- The Russian attack on the Turkish fleet at the Battle of Chesma, 1770.

- Thomas Cochrane's attack on the French in the Battle of the Basque Roads, 1809.

- Multiple successful Greek attacks on large Turkish ships of the line during the Greek War of Independence, 1821–1832.

- Chinese attacks on British ships during the First Opium War, 1839–1842.

See also

- List of fireships of the Royal Navy

- MT explosive motor boat

- Operation Lucid

- Shin'yō-class suicide motorboat

References

- The Fireship and its Role in the Royal Navy by James Coggeshall. Master's Thesis, Texas A&M University, 1997

- The Fireship and its Role in the Royal Navy by James Coggeshall. Master's Thesis, Texas A&M University, 1997, pp. 7-11

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, 7.53.4

- The Fireship and its Role in the Royal Navy by James Coggeshall. Master's Thesis, Texas A&M University, 1997, p. 2

- The Fireship and its Role in the Royal Navy by James Coggeshall. Master's Thesis, Texas A&M University, 1997, p. 15

- The Fireship and its Role in the Royal Navy by James Coggeshall. Master's Thesis, Texas A&M University, 1997, p. 16

- The Fireship and its Role in the Royal Navy by James Coggeshall. Master's Thesis, Texas A&M University, 1997, p. 17–18

- The Fireship and its Role in the Royal Navy by James Coggeshall. Master's Thesis, Texas A&M University, 1997, p. 18–19

- Brewer, David (2003). The Greek War of Independence: The Struggle for Freedom from Ottoman Oppression and the Birth of the Modern Greek Nation. Overlook Press. p 93

- Foote, Shelby (2011-01-26). The Civil War: A Narrative: Volume 1: Fort Sumter to Perryville. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 355. ISBN 9780307744678. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- Tucker, Spencer (2002). A Short History of the Civil War at Sea. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780842028684. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- "Battle of Britain, September 1940". naval-history.net.

- Greene, Jack & Massignani, Alessandro: The Naval War in the Mediterranean, 1940–1943. Chatam Publishing, London, 1998, page 141. ISBN 1-86176-057-4

- Sadkovich, James: The Italian Navy in World War II. Greenwood Press, Westport, 1994, page 25. ISBN 0-313-28797-X

- Suicide bombing attack claims first Coast Guardsman since Vietnam War by Kendra Helmer. Stars and Stripes, 27 April 2004

- Alexander's mole

- The Fireship and its Role in the Royal Navy by James Coggeshall. Master's Thesis, Texas A&M University, 1997, pp. 14–16

- The Fireship and its Role in the Royal Navy by James Coggeshall. Master's Thesis, Texas A&M University, 1997, pp. 16–18

External links

![]()