Firedamp

Firedamp is flammable gas found in coal mines. It is the name given to a number of flammable gases, especially methane. It is particularly found in areas where the coal is bituminous. The gas accumulates in pockets in the coal and adjacent strata, and when they are penetrated, the release can trigger explosions. Historically, if such a pocket was highly pressurized, it was termed a "bag of foulness".[1]

Name

Damps is the collective name given to all gases (other than air) found in coal mines in Great Britain. The word corresponds to German Dampf, the name for "vapour".[2]

Alongside firedamp, other damps include blackdamp (nonbreathable mixture of carbon dioxide, water vapour, and other gases), whitedamp (carbon monoxide and other gases produced by combustion), poisonous, explosive stinkdamp (hydrogen sulfide), with its characteristic "rotten egg" odour, and the insidiously lethal afterdamp (carbon monoxide and other gases) produced following explosions of firedamp or coal dust.

Contribution to mine deaths

Firedamp is explosive at concentrations between 4% and 16%, with most explosions occurring at around 10%. It caused many deaths in coal mines before the invention of the Geordie lamp and Davy lamp.[3] Even after the safety lamps were brought into common use, firedamp explosions could still occur from sparks produced when coal contaminated with pyrites was struck with metal tools. The presence of coal dust in the air increased the risk of explosion with firedamp, and could cause explosions even in the absence of firedamp. The Tyneside coal mines in England had the deadly combination of bituminous coal contaminated with pyrites, and there were a great number of deaths due to accidents caused by firedamp explosions, including 102 dead at Wallsend in 1835.[3]

The problem of firedamp in mines had been brought to the attention of the Royal Society by 1677,[4] and in 1733 James Lowther reported that as a shaft was being sunk for a new pit at Saltom near Whitehaven, a major release had taken place on breaking through a layer of black stone into a coal seam. Ignited with a candle, it had given a steady flame "about half a Yard in Diameter, and near two Yards high". The flame being extinguished, and a wider penetration through the black stone made, re-ignition of the gas gave a bigger flame, a yard in diameter and about three yards high which was only extinguished with difficulty. The blower was panelled off from the shaft, and piped to the surface where over two and a half years later it continued as fast as ever, filling a large bladder in a few seconds.[5] The society members elected Sir James Fellow, but were unable to come up with any solution, or improve on the assertion (eventually found to be incorrect) of Carlisle Spedding, the paper's author, that "this sort of Vapour, or damp Air, will not take Fire except by Flame; Sparks do not affect it, and for that Reason it is frequent to use Flint and Steel in Places affected with this sort of Damp, which will give a glimmering Light, that is a great Help to the Workmen in difficult Cases."

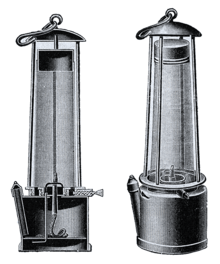

A great step forward in countering the problem of firedamp came when safety lamps, intended to provide illumination whilst being incapable of igniting firedamp, were brought forward by both George Stephenson and Humphry Davy, in response to accidents such as the Felling mine disaster near Newcastle upon Tyne which killed 92 people on 25 May 1812. Davy experimented with brass gauze, determining the maximum size of the gaps and the optimum wire thickness to prevent a flame passing through the gauze.[6] If a naked flame was thus enclosed totally by such a gauze, then methane could pass into the lamp and burn safely above the flame. Stephenson's lamp (the "Geordie lamp") worked on a different principle: the flame was enclosed by glass; air access to the flame was through tubes sufficiently narrow that the flame could not burn-back in incoming firedamp, and the exiting gases were too weak in oxygen to allow the enclosed flame to reach the surrounding atmosphere. Both principles were combined in later versions of safety lamps.

After the widespread introduction of the safety lamp, explosions continued because the early lamps were fragile and easily damaged. For example, the iron gauze on a Davy lamp only needed to lose one wire to become unsafe. The light was also very poor (compared to a naked flame) and there were continuous attempts to improve the basic design. The height of the cone of burning methane in a flame safety lamp can be used to estimate the concentration of the gas in the local atmosphere. It was not until the 1890s that safe and reliable electric lamps became available in collieries.

See also

References

- William Stukeley Gresly (1882). "Bag of foulness". A Glossary of Terms Used in Coal Mining. London: E. & F.N. Spon.

- Oxford English Dictionary: damp, n.1

- Holland, John (1841). The History and Description of Fossil Fuel, the Collieries, and Coal Trade of Great Britain. London: Whittaker and Co (Digital edition Kress Library of Business and Economics, Harvard University). pp. 267–8.

- "Of Damps in Mines" by R Moslyn(?) (no 136. p890, volume XII (1677)) reprinted in The Philosophical transactions of the Royal society of London, from their commencement in 1665, in the year 1800. London: C R Hutton. 1809. pp. 398–401. - reports an event at Moslyn in Flintshire; both here and in the author's name Mostyn seems more plausible

- "An Account of the Damp Air in a Coal-Pit of Sir James Lowther, Bart. Sunk within 20 Yards of the Sea; Communicated by Him to the Royal Society". Philosophical Transactions. 38 (427–435): 109–113. 1733. doi:10.1098/rstl.1733.0019. JSTOR 103830.

- Humphry Davy (1816). On the Fire-damp of Coal Mines: From the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. With an Advertisement : Containing an Account of an Invention for Lighting the Mines and Consuming the Fire-damp Without Danger to the Miner. Bulmer.

- "Experiments Show How Gas Explodes in a Mine", Popular Science monthly, February 1919, Unnumbered page, Scanned by Google Books: https://books.google.com/books?id=7igDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PT21