Cape Finisterre

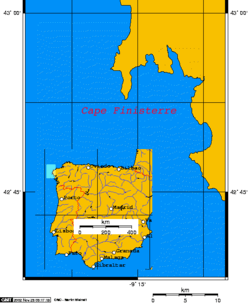

Cape Finisterre (/ˌfɪnɪˈstɛər/,[1][2] also US: /-tɛri/;[3] Galician: Cabo Fisterra [fisˈtɛrɐ]; Spanish: Cabo Finisterre [finisˈtere]) is a rock-bound peninsula on the west coast of Galicia, Spain.[4]

| Cape Finisterre | |

|---|---|

Finisterre on the Atlantic coast of Galicia | |

| |

| Location | Galicia, |

| Coordinates | 42°52′57″N 9°16′20″W |

| Offshore water bodies | Atlantic Ocean |

In Roman times it was believed to be the end of the known world. The name Finisterre, like that of Finistère in France, derives from the Latin finis terrae, meaning "end of the earth". It is sometimes said to be the westernmost point of the Iberian Peninsula. However, Cabo da Roca in Portugal is about 16.5 kilometres (10.3 mi) further west and thus the westernmost point of continental Europe. Even in Spain Cabo Touriñán is farther west.

Monte Facho is the name of the mountain on Cape Finisterre, which has a peak that is 238 metres (781 ft) above sea level. A prominent lighthouse is at the top of Monte Facho. The seaside town of Fisterra is nearby.

The Artabri were an ancient Gallaecian Celtic tribe that once inhabited the area.

Geography

Cape Finisterre has several beaches, including O Rostro, Arnela, Mar de Fora, Langosteira, Riveira, and Corbeiro. Many of the beaches are framed by steep cliffs leading down to the Mare Tenebrosum (or dark sea, the name of the Atlantic in the Middle Ages).

There are several rocks in this area associated with religious legends, such as the "holy stones", the "stained wine stones", the "stone chair", and the tomb of the Celtic crone-goddess Orcabella.[5]

Pilgrimage

Cape Finisterre is the final destination for many pilgrims on the Way of St. James, the pilgrimage to the shrine of the apostle Saint James the Great in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela.[6] Cape Finisterre is about a 90 km walk from Santiago de Compostela.

The origin of the pilgrimage to Finisterre is not certain. However, it is believed to date from pre-Christian times and was possibly associated with Finisterre's status as the "edge of the world" and a place to see the last sun of the day.[7] The tradition continued in medieval times, when "hospitals" were established to cater to pilgrims along the route from Santiago de Compostela to Finisterre.[8]

Some pilgrims continue on to Muxía, which is a day's walk away.[9]

Gallery

Camino de Santiago, Fisterra

Camino de Santiago, Fisterra Pilgrim's boot in Fisterra

Pilgrim's boot in Fisterra Fisterra lighthouse

Fisterra lighthouse

Pre-Christian beliefs

In the area there are many pre-Christian sacred locations. There was an "Altar Soli" on Cape Finisterre,[10] where the Celts engaged in sun worship and assorted rituals.[11][12]

Greco-Roman historians called the local residents of Cape Finisterre the "Nerios".[13] Monte Facho was the place where the Celtic Nerios from Duio[14] carried out their offerings and rites in honor of the sun. Monte Facho is the site of current archaeological investigations and there is evidence of habitation on Monte Facho circa 1000 BCE.[15] There is a Roman Road to the top of Monte Facho and the remnants of ancient structures on the mountain.[16]

San Guillerme, also known as St. William of Penacorada,[17] lived in a house located on Monte Facho. Near San Guillerme's house is a stone now known as "St William's Stone" (Pedra de San Guillerme). Sterile couples used to copulate on St. William's Stone to try to conceive, following a Celtic rite of fertility.[10]

Maritime history

This was where the Phoenicians sailed from to trade with Bronze Age Britain,[18] perhaps to Mount Batten.

Because it is a prominent landfall on the route from northern Europe to the Mediterranean, several nearby battles are named the "Battle of Cape Finisterre". There was the First Battle of Cape Finisterre (1747) and the Battle of Cape Finisterre (1805). The coast, known locally as the Costa da Morte (Death Coast),[19] has been the site of numerous shipwrecks and founderings, including that of the British ironclad HMS Captain, leading to the loss of nearly 500 lives, in 1870.

Additionally, laws governing the colonies of the British Empire (including the 1766 amendment to the Sugar Act of 1764) used the latitude of Cape Finisterre as the latitude past which certain goods could not be shipped north directly between British colonies. For instance, it was forbidden to ship sugar cane directly from Jamaica to Nova Scotia, as such a transaction crossed through this latitude. Instead, the laws required that the sugar cane be shipped first from Jamaica to England, where it would be re-exported to Nova Scotia. It also applied to the export of cotton from British America, and later contributed to British support for the pro-slavery South during the American Civil War (see History of cotton (section Civil War)).

Likewise, the latitude of Cape Finisterre was used to signal that a change of flags flown by Norwegian and Swedish merchant ships was required. Following independence and the subsequent union with Sweden in 1814, Norwegian merchant ships were required to fly the Swedish flag (until 1818) and the Swedish flag with the Norwegian (the Dannebrog with the Norwegian lion) flag in the canton. From 1818 - 1821 Swedish ships also flew this flag in place of the pure Swedish flag (until 1844) when sailing south of Cape Finisterre.

Finisterre was the former name of the current FitzRoy sea area used in the UK Shipping Forecast. In 2002, it was renamed FitzRoy – in honour of the founder of the Met Office) – to avoid confusion with the smaller sea area of the same name featuring in the marine forecasts produced by the French and Spanish meteorological offices.

In popular culture

- In the Gilbert & Sullivan operetta Ruddigore, Richard Dauntless sings of shipping out in "a revenue sloop" and encountering a French merchantman "off Cape Finistere."

- In the film Night Train to Lisbon (2013), Amadeu and Estafania spend the night and the morning in the car at Cape Finisterre. Then, Amadeu is shown sitting on the cliff writing his memoirs on which the film centers.

References

- "Finisterre". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "Finisterre, Cape". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "Finisterre, Cape". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Photograph of Cape Finisterre, seen from the air, facing north

- Orcabella is a Celtic goddess that takes the form of a hag and has a prodigious sexual appetite. Humans cannot hurt Orcabella; they only see her or feel her. Orcabella has many features that are similar to the Irish crone-goddess, Cailleach Bhéirre (LA MITOLOGÍA Y EL FOLKLORE DE GALICIA Y LAS REGIONES CÉLTICAS DEL NOROESTE EUROPEO ATLÁNTICO Archived 2017-05-11 at the Wayback Machine, Manuel ALBERRO, Inst. of Cornish Studies, University of Exeter)

- "Cape Finisterre - Galicia".

- "The last sunset on mainland Europe". Cartography and Geographic Information Science.

- "The way of Saint James".

- "The Fisterra and Muxía way".

- Justel, César (14 April 2008). "Galicia mágica Ritos y piedras". ABC. Vocento. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- Conde, Arturo (2006). "Finisterre or The End of the World - Finisterre, Galicia, Spain". BootsnAll Travel Network. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- "Fisterra". Finisterrae. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- "History of Corcubion". Corcubion City Council's Website. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- "Entrance to the Land´s End in the Fisterra´s peninsula, legendary parishes of San Martiño and San Vicente of Duio have got the Fisterra´s solitude and dramatic beauty atmosphere". finisterrae.com. 6 October 2008. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Arqueología". Vigo en Fotos (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- Sweetkinky (20 December 2005). "Monte Facho". Google Earth Community. Archived from the original on 7 October 2008. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- "St. William of Penacorada". Catholic online. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- Hawkins, Christopher (1811). Observations on the Tin Trade of the Ancients in Cornwall. London: Oxford University. pp. 93. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- "Stricken oil tanker sinks". BBC News. BBC. 19 November 2002. Retrieved 25 March 2019.