Fidelia Bridges

Fidelia Bridges (May 19, 1834 – May 14, 1923) was an American artist of the late 19th century, and one of the few women to have a successful career in that period. She was known for delicately detailed paintings that captured flowers, plants, and birds in their natural settings. Although she began as an oil painter, she later gained a reputation as an expert in watercolor painting. She was the only woman among a group of seven artists in the early years of the American Watercolor Society. Some of her work was published as illustrations in books and magazines and on greeting cards.

Fidelia Bridges | |

|---|---|

Oliver Ingraham Lay (1845–1890), Fidelia Bridges, Smithsonian American Art Museum | |

| Born | May 19, 1834 Salem, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | May 14, 1923 (aged 88)[1] Canaan, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Resting place | Mountain View Cemetery, North Canaan, Connecticut 42°0′55.25″N 73°20′19.71″W |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | William Trost Richards, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Pre-Raphaelite |

| Patron(s) | Mark Twain |

Early life

Fidelia Bridges was born in Salem, Massachusetts, to Henry Gardiner Bridges (1789-1849), a sea captain,[2] and Eliza (Chadwick) Bridges (1791-1850).[3][4] She was orphaned at the age of fifteen when her mother and father died within months of each other.[2][5] In 1849, Henry Bridges fell ill and was taken to Portuguese Macau, where he died in December. Eliza died in March 1850, just three hours before the news of her husband's death arrived in Salem.[3][4]

The couple left four children, Eliza, Elizabeth, Fidelia, and Henry. They were living at 100 Essex Street, now known as the Fidelia Bridges Guest House, but moved to a more affordable home on the same street after their parents' death.[4] Fidelia's older sister Eliza was a schoolteacher and became the guardian of her younger siblings.[2][5]

Fidelia took up drawing during her convalescence from an illness. She became a friend of the artist and art school owner Anne Whitney.[4] After she regained her health, Fidelia became a live-in mother's helper in the household of William Augustus Brown, a Quaker who had been a Salem ship-holder before moving to Brooklyn, New York, where he became a successful wholesale produce merchant.[2][4][5] The Bridges moved to Brooklyn, too, and in 1854 Eliza established a school there.[2][5] Eliza died in 1856 of tuberculosis, and Fidelia and her older sister Elizabeth then ran the school.[4][5]

Early career and education

Bridges, however, soon abandoned teaching in order to concentrate on her drawing lessons. In 1860,[5] after being inspired by her friend Anne Whitney, she enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia with William Trost Richards and became very close to his family.[2] By 1862, she had her own studio in downtown Philadelphia. Having remained friends with the Richards family, she accompanied them to Lake George and Lehigh Valley of Pennsylvania and New Jersey on sketching trips.[5] He was a Pre-Raphaelite advocate and her style was greatly influenced by him. Richards said of her work that it was "the unaffected expression of a great joy in the beauty of nature— a joy which is after all the fountain of all that is finest in art; and one could not see the rich treasures of Miss Bridge's portfolios of studies without feeling this."[6]

Through Richards, Bridges met museum curators and patrons of the arts,[7] several of whom became collectors of her paintings.[5] She exhibited her works at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.[7]

In 1865, Bridges left Philadelphia and established a studio on the top floor of the Browns' house in Brooklyn,[5] where Anne Whitney also worked and lived with her companion Adeline Manning, a painter from Boston.[7]

Career and studies in Rome

After the American Civil War she studied for a year[2] in Rome and lived and traveled with Adeline Manning and Anne Whitney.[5][7] She maintained her style of intricate botanical works in oil. Bridges returned to the United States in the fall of 1868. Her works were then exhibited at the National Academy of Design.[5] In 1871, watercolor was a respected medium and she quickly gained popularity with her watercolor depictions of flowers and birds. Her pictures, however, were not mere photographic reproductions of what she saw; with the imagination of the true artist, she infused her subjects with a deep poetic meaning.[6][5] Bridges "combined the temper of romanticism with the technique of a scientist," according to Frederick Sharf's biography of her.[7]

Bridges was considered a specialist in her field and focused on the beauty and serenity of microscopic details in nature.[2][5] One of her favored sites was Stratford, Connecticut, where she enjoyed the wildflowers and other subject matter in the area's flats and meadows. The birds found in the green salt grass lined banks of the Housatonic River were also of interest. She made some of her best paintings of the scenes from her summer visits from 1871 to 1888 with Oliver Ingraham Lay and his family. Paintings such as Daisies and Clover and Thrush in Wild Flowers are examples of her works during this period.[5] She lived in Stratford, Connecticut by 1890 when she ministered to the ailing Lay who died that year.[8]

She was elected as a National Academy of Design associate in 1873 and one year later became the only woman of seven artists in the American Society of Painters in Watercolor (now The American Watercolor Society).[2][5] She exhibited her work sporadically from 1863 until 1908.[2]

In 1876, she exhibited three paintings at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition.[7] That year, many of her paintings were reproduced and sold by publisher and lithographer Louis Prang. St. Nicholas Magazine and the August 1876 edition of Scribner's Monthly contained her illustrations.[2][5] She illustrated John Burrough's Bird and Birds published by Scribner's Monthly by 1877.[9] This success eventually led to a job as a designer for Prang's firm. For this job Bridges designed Christmas cards and she kept the job until 1899.[2][5]

Bridges visited England between 1879 and 1880. During that time she visited her brother Henry, who worked there as a tea-taster and traveled to China in the commission of his work. Her works, which reflected an Oriental aesthetic with plain background and asymmetrical compositions, were exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts.[5] Some of her compositions are similar to that of the Flower and Bird series of Japanese woodblock print artist, Hiroshige.[10]

After her extended visit to England, Bridges returned to the Browns home, where she continued to work and live much of the time. She spent a year working as a governess to Mark Twain's three daughters starting in 1883; Twain was also a collector of her work.[5]

In collaboration with the illustrator and book editor Susie Barstow Skelding, she created several books of poetry with her bird illustrations, including Winged Flower Lovers, and Songsters of the Branches during the 1880s.[11] Her illustrations of birds were published in an 1888 book of poems, What the Poets Sing of Them and the book Favorite Birds.[5]

Bridges exhibited her work at the Palace of Fine Arts at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois.[12]

Personal life

.jpg)

Bridges never married, but had good friends and relationships throughout her life.[7] She moved to Canaan, Connecticut in 1892 and lived in a cottage on a hill, overlooking a stream and with a beautiful flower garden that attracted birds and became the subject of many paintings.[nb 1] She led a quiet lifestyle, and occasionally traveled to Europe and New York.[6][5] She continued to exhibit her works, including the American Society of Painters, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the National Academy of Design.[7]

She soon became a familiar village figure, tall, elegant, beautiful even in her sixties, her hair swept back, her attire always formal, even when sketching in the fields or rider her bicycle through town. Her life was quiet and un-ostentatious, her friends unmarried ladies of refinement and of literary and artistic task who she joined for woodland picnics and afternoon teas.

— Edward T. James and Janice Wilson James[5]

Along with artist Howard Pyle, Bridges became a sustaining member of the American Forestry Association, which was founded to protect forests in the United States following "an eloquent plea" from President Theodore Roosevelt.[14]

Bridges died following a stroke just a few days before turning eighty-nine, on May 14, 1923 in Canaan, Connecticut.[1][2][15] A service was held for Bridges in her home on May 16, 1923[1] and she was buried at the Mountain View Cemetery in Canaan.[16]

Legacy

The Bridges family home was named the Fidelia Bridges Guest Home in her name.[4] In Canaan, a bird sanctuary was named in her honor.[7]

Posthumous exhibitions of her work occurred in 1984 at the Whitney Museum of American Art's Reflection of Nature show and at The New Path, Ruskin and the American Pre-Raphaelites at the Brooklyn Museum of Art.[7] The Smithsonian Institution has two of her works.[7][17] Another work is held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and her painting of the Benning Wentworth House is in the Strawbery Banke museum in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.[18]

Gallery

Still Life with Robin's Nest, 1863

Still Life with Robin's Nest, 1863 Thistle in a Field, 1875

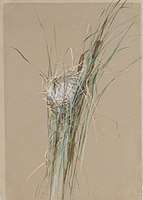

Thistle in a Field, 1875 Fidelia Bridges, Bird's Nest in Cattails, 1875, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fidelia Bridges, Bird's Nest in Cattails, 1875, Metropolitan Museum of Art Pink Cyclamen, c. 1870s

Pink Cyclamen, c. 1870s Thrushes' Nest, 1878

Thrushes' Nest, 1878 Grass and Poison Ivy, c. 1880

Grass and Poison Ivy, c. 1880

Notes

- William T. Richards made a painting of her garden in 1901 entitled Fidelia Bridge's Garden in Canann, Connecticut, 1901.[13]

References

- "Obituary: Fidelia Bridges" New York Times. May 15, 1923.

- Dearinger, David B (2004). Paintings and Sculpture in the Collection of the National Academy of Design. Hudson Hills Press. ISBN 978-1-55595-029-3.

- Lindsay Ride; May Ride; Bernard Mellor (1 November 1995). An East India Company Cemetery: Protestant Burials in Macao. Hong Kong University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-962-209-384-3.

- A Forgotten Master Artist, Fidelia Bridges. Salem Patch. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

- Edward T. James; Janet Wilson James; Paul S. Boyer (1 January 1971). Notable American Women, 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary. Harvard University Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-674-62734-5.

- William Farrand Felch; George C. Atwell; H. Phelps Arms. The Connecticut Magazine. Connecticut Magazine Company; 1900. p. 583–588.

- Carol Kort and Liz Sonneborn. A to Z of American Women in the Visual Arts. New York: Facts on File, 2002. pp. 32-33. ISBN 0-8160-4397-3.

- David Bernard Dearinger. Paintings and Sculpture in the Collection of the National Academy of Design: 1826-1925. Hudson Hills; 2004. ISBN 978-1-55595-029-3. p. 351.

- "Scribner's Monthly for 1877-1878: Out-of-Door Papers" Denton Journal. December 8, 1877. p. 1.

- Katherine E. Manthorne. The Voice of Nature. Newington-Cropsey Cultural Studies Center. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- "Books and Authors: A Review of the Literary Field. Brief Notes about New Books." The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. October 23, 1887. p. 5.

- Nichols, K. L. "Women's Art at the World's Columbian Fair & Exposition, Chicago 1893". Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- Fidelia Bridge's Garden in Canann, Connecticut, 1901. National Academy Museum. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- "Forestry Society Grows: Many New Adherents to the Cause of Woodlands." The Washington Post. April 16, 1907. p. 15.

- Edward T. James; Janet Wilson James; Paul S. Boyer (1 January 1971). Notable American Women, 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary. Harvard University Press. pp. 238–239. ISBN 978-0-674-62734-5.

- Fidelia Bridges. Find a Grave. Retrieved March 16, 2014. Note: Source just for the cemetery name, tombstone information is aligned with dates and places of birth and death.

- Fidelia Bridges. Smithsonian Institution American Art Museum. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- Bird's Nest in Cattails. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fidelia Bridges. |

- Fidelia Bridges artworks at The Athenaeum

- Fidelia Bridges at Union List of Artist Names, Getty Research Institute

- http://strawberybanke.pastperfectonline.com/webobject/444C1548-6FC5-434F-A087-788790283170 Painting at the Strawbery Banke Museum.