Federalist No. 55

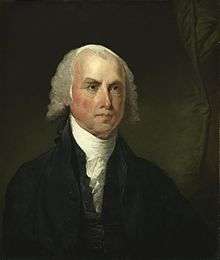

Federalist No. 55 is an essay by James Madison, the fifty-fifth of The Federalist Papers. It was published on February 13, 1788 under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist Papers were published. It is titled "The Total Number of House of Representatives". It is the first of four papers defending the number of members in the House of Representatives against the critics who believe the number of members to be inadequate. The critics presume that there aren't enough representatives to defend the country against the small group of legislators who are violating the rights of the people. In this paper, Madison examines the size of the United States House of Representatives.[1]

The paper discusses critics' objections to the relatively small size of the House of Representatives (sixty-five members) because they believe that there aren't enough representatives to defend the country against the small group of legislators who are violating the rights of the people. Madison notes that the size of the House will increase as population increases. In addition, he states that the small size does not put the public liberty in danger because of the checks and balances relationship the House of Representatives has with the state legislatures, as well as the fact that every member is voted in by the people every two years.[1]

Background

The House of Representatives is one of Congress' two chambers, and a part of the legislative branch. The House is responsible for making and passing federal laws.[2] Each Representative is elected to a two-year term.[3] The number of voting Representatives is fixed at 435, proportionally representing the population of the fifty states in the United States of America. The Representatives do not only introduce bills and resolutions, but they also serve on Committees and offer amendments.[2]

Article 1, Section 2 of the Constitution provides for both the minimum and maximum sizes for the House of Representatives. Currently, there are five delegates representing the District of Columbia, the Guam, American Samoa, The Virgin Islands, northern Mariana Islands, and the Commonwealth. Puerto Rico is represented by a resident commissioner. The delegates and resident commissioner possess the same powers as other members of the House, except that they may not vote when the House is meeting as the House of Representatives.[2]

Number of Representatives

Congress has the power to regulate the size of the House of Representatives, and the size of the House has varied through the years due to the admission of new states and reapportionment following a census. The House of Representatives began with sixty-five members and now, consists of 435 members.

| Year | 1789 | 1791 | 1793 | 1803 | 1813 | 1815 | 1817 | 1819 | 1821 | 1833 | 1835 | 1843 | 1845 | 1847 | 1851 | 1853 | 1857 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representatives | 65 | 69 | 105 | 141 | 182 | 183 | 185 | 187 | 213 | 240 | 242 | 223 | 225 | 227 | 233 | 234 | 237 |

| Year | 1861 | 1863 | 1865 | 1867 | 1869 | 1873 | 1883 | 1889 | 1891 | 1893 | 1901 | 1911 | 1913 | 1959 | 1961 | 1963 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representatives | 178 | 183 | 191 | 193 | 243 | 293 | 325 | 330 | 333 | 357 | 386 | 391 | 435 | 436 | 437 | 435 |

In 1911, Congress passed The Apportionment Act of 1911, also known as Public Law 62–5, which says that the United States House of Representatives can have no more than 435 members. Each state, is given at least one representative and the number of representatives per state varies based on population.

Madison's Argument

There is no fixed numeric formula for the ratio between the population and the number of Representatives; the members of the House will increase as new states are added and the population grows. Madison reasons with those who are against the size of the House of Representatives because they do not trust the legislators in the following quote: "The truth is that in all cases a certain number [of representatives] at least seems to be necessary to secure the benefits of free consultation and discussion, and to guard against too easy a combination for improper purposes; as, on the other hand, the number ought at most to be kept within a certain limit, in order to avoid the confusion and intemperance of a multitude. In all very numerous assemblies, of whatever characters composed, passion never fails to wrest the scepter from reason. Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob."[4] He tells the public, no republican government can guarantee that it will be completely free of infringement but the people must also have a certain degree of trust in the government's power to protect them and to ensure the safety of the republic. To further reassure the people, the system of "checks and balances" was put in place to ensure that no branch (the executive, judicial, or legislative) would have more power than the other.[4]

Modern Analysis

Since The Apportionment Act of 1911 was passed, people have been concerned about the laws/ bills that the House of Representatives passes. The House can make laws that create new taxes, it aids in determining the fiscal policy, it guides federal spending and taxation etc.[5] The laws made by the House have can directly affect the population but as Madison said in the Federalist Paper, "Were the pictures which have been drawn by the political jealousy of some among us faithful likenesses of the human character, the inference would be, that there is not sufficient virtue among men for self-government; and that nothing less than the chains of despotism can restrain them from destroying and devouring one another"[4] meaning, the Republican government depends on the virtue/trust of the people. "Republican government presupposes the existence of these qualities in a higher degree than any other form [of government]."[4]

References

- "The Federalist Papers - Congress.gov Resources -". www.congress.gov. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- "The House Explained · House.gov". www.house.gov. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- "The United States House of Representatives · House.gov". www.house.gov. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- Madison, James. "Federalist 55" (PDF).

- "How the US House of Representatives Affects the US Economy". The Balance. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |