Feces

Feces (or faeces) are the solid or semisolid remains of food that could not be digested in the small intestine. Bacteria in the large intestine further break down the material.[1][2] Feces contain a relatively small amount of metabolic waste products such as bacterially altered bilirubin, and the dead epithelial cells from the lining of the gut.[1]

Feces are discharged through the anus or cloaca during defecation.

Feces can be used as fertilizer or soil conditioner in agriculture. It can also be burned as fuel or dried and used for construction. Some medicinal uses have been found. In the case of human feces, fecal transplants or fecal bacteriotherapy are in use. Urine and feces together are called excreta.

Characteristics

- Feces samples

- Bear scat

Bear scat showing consumption of bin bags

Bear scat showing consumption of bin bags The cassowary disperses plant seeds via its feces

The cassowary disperses plant seeds via its feces Earthworm feces aid in provision of minerals and plant nutrients in an accessible form

Earthworm feces aid in provision of minerals and plant nutrients in an accessible form

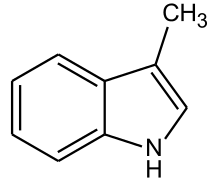

The distinctive odor of feces is due to skatole, and thiols (sulfur-containing compounds), as well as amines and carboxylic acids. Skatole is produced from tryptophan via indoleacetic acid. Decarboxylation gives skatole.[3][4]

The perceived bad odor of feces has been hypothesized to be a deterrent for humans, as consuming or touching it may result in sickness or infection.[5] Human perception of the odor may be contrasted by a non-human animal's perception of it; for example, an animal who eats feces may be attracted to its odor.

Physiology

Feces are discharged through the anus or cloaca during defecation. This process requires pressures that may reach 100 millimetres of mercury (3.9 inHg) in humans and 450 millimetres of mercury (18 inHg) in penguins.[6][7] The forces required to expel the feces are generated through muscular contractions and a build-up of gases inside the gut, prompting the sphincter to relieve the pressure and to release the feces.[7]

Ecology

After an animal has digested eaten material, the remains of that material are discharged from its body as waste. Although it is lower in energy than the food from which it is derived, feces may retain a large amount of energy, often 50% of that of the original food.[8] This means that of all food eaten, a significant amount of energy remains for the decomposers of ecosystems. Many organisms feed on feces, from bacteria to fungi to insects such as dung beetles, who can sense odors from long distances.[9] Some may specialize in feces, while others may eat other foods. Feces serve not only as a basic food, but also as a supplement to the usual diet of some animals. This process is known as coprophagia, and occurs in various animal species such as young elephants eating the feces of their mothers to gain essential gut flora, or by other animals such as dogs, rabbits, and monkeys.

Feces and urine, which reflect ultraviolet light, are important to raptors such as kestrels, who can see the near ultraviolet and thus find their prey by their middens and territorial markers.[10]

Seeds also may be found in feces. Animals who eat fruit are known as frugivores. An advantage for a plant in having fruit is that animals will eat the fruit and unknowingly disperse the seed in doing so. This mode of seed dispersal is highly successful, as seeds dispersed around the base of a plant are unlikely to succeed and often are subject to heavy predation. Provided the seed can withstand the pathway through the digestive system, it is not only likely to be far away from the parent plant, but is even provided with its own fertilizer.

Organisms that subsist on dead organic matter or detritus are known as detritivores, and play an important role in ecosystems by recycling organic matter back into a simpler form that plants and other autotrophs may absorb once again. This cycling of matter is known as the biogeochemical cycle. To maintain nutrients in soil it is therefore important that feces return to the area from which they came, which is not always the case in human society where food may be transported from rural areas to urban populations and then feces disposed of into a river or sea.

Human feces

Depending on the individual and the circumstances, human beings may defecate several times a day, every day, or once every two or three days. Extensive hardening of the feces that interrupts this routine for several days or more is called constipation.

The appearance of human fecal matter varies according to diet and health.[11] Normally it is semisolid, with a mucus coating. A combination of bile and bilirubin, which comes from dead red blood cells, gives feces the typical brown color.[1][2]

After the meconium, the first stool expelled, a newborn's feces contain only bile, which gives it a yellow-green color. Breast feeding babies expel soft, pale yellowish, and not quite malodorous matter; but once the baby begins to eat, and the body starts expelling bilirubin from dead red blood cells, its matter acquires the familiar brown color.[2]

At different times in their life, human beings will expel feces of different colors and textures. A stool that passes rapidly through the intestines will look greenish; lack of bilirubin will make the stool look like clay.

Uses of animal feces

Fertilizer

The feces of animals, e.g. guano and manure often are used as fertilizer.[12]

Energy

Dry animal dung is burned and used as a fuel source in many countries around the world. Some animal feces, especially that of camel, bison, and cattle, are fuel sources when dried.[13]

Animals such as the giant panda[14] and zebra[15] possess gut bacteria capable of producing biofuel. That bacteria, called Brocadia anammoxidans, can create the rocket fuel hydrazine.[16][17]

Coprolites and paleofeces

A coprolite is fossilized feces and is classified as a trace fossil. In paleontology they give evidence about the diet of an animal. They were first described by William Buckland in 1829. Prior to this they were known as "fossil fir cones" and "bezoar stones". They serve a valuable purpose in paleontology because they provide direct evidence of the predation and diet of extinct organisms.[18] Coprolites may range in size from a few millimetres to more than 60 centimetres.

Palaeofeces are ancient human feces, often found as part of archaeological excavations or surveys. Intact feces of ancient people may be found in caves in arid climates and in other locations with suitable preservation conditions. These are studied to determine the diet and health of the people who produced them through the analysis of seeds, small bones, and parasite eggs found inside. These feces may contain information about the person excreting the material as well as information about the material. They also may be analyzed chemically for more in-depth information on the individual who excreted them, using lipid analysis and ancient DNA analysis. The success rate of usable DNA extraction is relatively high in paleofeces, making it more reliable than skeletal DNA retrieval.[19]

The reason this analysis is possible at all is due to the digestive system not being entirely efficient, in the sense that not everything that passes through the digestive system is destroyed. Not all of the surviving material is recognizable, but some of it is. Generally, this material is the best indicator archaeologists can use to determine ancient diets, as no other part of the archaeological record is so direct an indicator.[20]

A process that preserves feces in a way that they may be analyzed later is called the Maillard reaction. This reaction creates a casing of sugar that preserves the feces from the elements. To extract and analyze the information contained within, researchers generally have to freeze the feces and grind it up into powder for analysis.[21]

Other uses

Animal dung occasionally is used as a cement to make adobe mudbrick huts,[22] or even in throwing sports such as cow pat throwing or camel dung throwing contests.[23]

Kopi luwak (pronounced [ˈkopi ˈlu.aʔ]), or civet coffee, is coffee made from coffee berries that have been eaten by and passed through the digestive tract of the Asian palm civet (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus). Giant pandas provide fertilizer for the world's most expensive green tea.[24] In Malaysia, tea is made from the droppings of stick insects fed on guava leaves.

In northern Thailand, elephants are used to digest coffee beans in order to make Black Ivory coffee, which is among the world's most expensive coffees.[24]

Dog feces were used in the tanning process of leather during the Victorian era. Collected dog feces, known as "pure", "puer", or "pewer",[25] were mixed with water to form a substance known as "bate". Enzymes in the dog feces helped to relax the fibrous structure of the hide before the final stages of tanning.[26]

Elephants, hippos, koalas and pandas are born with sterile intestines, and require bacteria obtained from eating the feces of their mothers to digest vegetation.

In India, cow dung and cow urine are major ingredients of the traditional Hindu drink Panchagavya. Politician Shankarbhai Vegad said in 2015, "I am witness to it, cow dung and urine are a 100 per cent cure for cancer".[27]

Terminology

Feces is the scientific terminology, while the term stool is also commonly used in medical contexts.[28] Outside of scientific contexts, these terms are less common, with the most common layman's term being poo (or poop in North American English). The term shit is also in common use, although is widely considered vulgar or offensive. There are many other terms, see below.

Etymology

The word faeces is the plural of the Latin word faex meaning "dregs". In most English-language usage, there is no singular form, making the word a plurale tantum;[29] out of various major dictionaries, only one enters variation from plural agreement.[30]

Synonyms

"Feces" is used more in biology and medicine than in other fields (reflecting science's tradition of classical Latin and New Latin)

- In hunting and tracking, terms such as dung, scat, spoor, and droppings normally are used to refer to non-human animal feces

- In husbandry and farming, manure is common.

- Stool is a common term in reference to human feces. For example, in medicine, to diagnose the presence or absence of a medical condition, a stool sample sometimes is requested for testing purposes.[31]

- The term bowel movement(s) (with each movement a defecation event) is also common in health care.

There are many synonyms in informal registers for feces, just like there are for urine. Many are euphemismistic, colloquial, or both; some are profane (such as shit), whereas most belong chiefly to child-directed speech (such as poo or poop) or to crude humor (such as crap, dump, load and turd.).

Feces of animals

The feces of animals often have special names, for example:

- Non-human animals

- As bulk material – dung

- Individually – droppings

- Cattle

- Bulk material – cow dung

- Individual droppings – cow pats, meadow muffins, etc.

- Deer (and formerly other quarry animals) – fewmets

- Wild carnivores – scat

- Otter – spraint

- Birds (individual) – droppings (also include urine as white crystals of uric acid)

- Seabirds or bats (large accumulations) – guano

- Herbivorous insects, such as caterpillars and leaf beetles – frass

- Earthworms, lugworms etc. – worm castings (feces extruded at ground surface)

- Feces when used as fertilizer (usually mixed with animal bedding and urine) – manure

- Horses – horse manure, roadapple (before motor vehicles became common, horse droppings were a big part of the rubbish communities needed to clean off roads)

Society and culture

Feelings of disgust

In all human cultures, feces elicit varying degrees of disgust in adults. Children under two years typically have no disgust response to it, suggesting it is culturally derived.[32] Disgust toward feces appears to be strongest in cultures where flush toilets make olfactory contact with human feces minimal.[33][34] Disgust is experienced primarily in relation to the sense of taste (either perceived or imagined) and, secondarily to anything that causes a similar feeling by sense of smell, touch, or vision.

Social media

There is a Pile of Poo emoji represented in Unicode as U+1F4A9 💩 PILE OF POO, called unchi or unchi-kun in Japan.[35][36]

See also

References

- Tortora, Gerard J.; Anagnostakos, Nicholas P. (1987). Principles of anatomy and physiology (Fifth ed.). New York: Harper & Row, Publishers. p. 624. ISBN 978-0-06-350729-6.

- Diem, K.; Lentner, C. (1970). "Faeces". in: Scientific Tables (Seventh ed.). Basle, Switzerland: CIBA-GEIGY Ltd. pp. 657–660.

- Whitehead, T. R.; Price, N. P.; Drake, H. L.; Cotta, M. A. (25 January 2008). "Catabolic pathway for the production of skatole and indoleacetic acid by the acetogen Clostridium drakei, Clostridium scatologenes, and swine manure". American Society for Microbiology:Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 74 (6): 1950–3. doi:10.1128/AEM.02458-07. PMC 2268313. PMID 18223109.

- Yokoyama, M. T.; Carlson, J. R. (1979). "Microbial metabolites of tryptophan in the intestinal tract with special reference to skatole". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 32 (1): 173–178. doi:10.1093/ajcn/32.1.173. PMID 367144.

- Curtis V, Aunger R, Rabie T (May 2004). "Evidence that disgust evolved to protect from risk of disease". Proc. Biol. Sci. 271 Suppl 4 (Suppl 4): S131–3. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0144. PMC 1810028. PMID 15252963.

- Langley, Leroy Lester; Cheraskin, Emmanuel (1958). The Physiology of Man. McGraw-Hill.

- Meyer-Rochow, Victor Benno; Gal, Jozsef (2003). "Pressures produced when penguins pooh?calculations on avian defaecation". Polar Biology. 27 (1): 56–58. doi:10.1007/s00300-003-0563-3. ISSN 0722-4060.

- Cummings, Benjamin; Campbell, Neil A. (2008). Biology, 8th Edition, Campbell & Reece, 2008: Biology (8th ed.). Pearson. p. 890.

- Heinrich B, Bartholomew GA (1979). "The ecology of the African dung beetle". Scientific American. 241 (5): 146–56. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1179-146.

- "Document: Krestel". City of Manhattan, Kansas. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- Stromberg, Joseph (January 22, 2015). "Everybody poops. But here are 9 surprising facts about feces you may not know". Vox. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- Dittmar, Heinrich; Drach, Manfred; Vosskamp, Ralf; Trenkel, Martin E.; Gutser, Reinhold; Steffens, Günter (2009). "Fertilizers, 2. Types". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.n10_n01.

- "Dried Camel Dung as fuel".

- Handwerk, Brian (September 11, 2013). "Panda Poop Might Help Turn Plants Into Fuel". nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- Ray, Kathryn Hobgood (August 25, 2011). "Cars Could Run on Recycled Newspaper, Tulane Scientists Say". Tulane News. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- Handwerk, Brian (November 9, 2005). "Bacteria Eat Human Sewage, Produce Rocket Fuel". National Geographic News. Retrieved December 3, 2019 – via wildsingapore.com.

- Harhangi, HR; Le Roy, M; van Alen, T; Hu, BL; Groen, J; Kartal, B; Tringe, SG; Quan, ZX; Jetten, MS; Op; den Camp, HJ (2012). "Hydrazine synthase, a unique phylomarker with which to study the presence and biodiversity of anammox bacteria". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 (3): 752–8. doi:10.1128/AEM.07113-11. PMC 3264106. PMID 22138989.

- "coprolites - Definitions from Dictionary.com".

- Poinar, Hendrik N.; et al. (10 April 2001). "A Molecular Analysis of Dietary Diversity for Three Archaic Native Americans". PNAS. 98 (8): 4317–4322. doi:10.1073/pnas.061014798. PMC 31832. PMID 11296282.

- Feder, Kenneth L. (2008). Linking to the Past: A Brief Introduction to Archaeology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533117-2.

- Stokstad, Erik (28 July 2000). "Divining Diet and Disease From DNA". Science. 289 (5479): 530–531. doi:10.1126/science.289.5479.530. PMID 10939960.

- "Your Home Technical Manual – 3.4d Construction Systems – Mud Brick (Adobe)". Archived from the original on 2007-07-06. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- "Dung Throwing contests". Archived from the original on October 11, 2007.

- Topper, R (15 October 2012). "Elephant Dung Coffee: World's Most Expensive Brew Is Made With Pooped-Out Beans". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- "pure". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) n., 6

- "Rohm and Haas Innovation - The Leather Breakthrough". Rohmhaas.com. 1909-09-01. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- Ramachandran, Smriti Kak (March 19, 2015). "Cow dung, urine can cure cancer: BJP MP". The Hindu. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- "stool" – via The Free Dictionary.

- "Feces definition – Medical Dictionary definitions of popular medical terms easily defined on MedTerms". Medterms.com. 2012-03-19. Retrieved 2013-11-11.

- Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Steven Dowshen, MD (September 2011). "Stool Test: Bacteria Culture". Kidshealth. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- Moore, Alison M. (8 November 2018). "Coprophagy in nineteenth-century psychiatry". Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease. 30 (sup1): 1535737. doi:10.1080/16512235.2018.1535737. PMC 6225515. PMID 30425610.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- https://www.upworthy.com/yes-poop-is-gross-but-thats-not-the-only-reason-for-its-shameful-social-stigma

- https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20131111-hate-poo-theres-good-reason-why

- "The Oral History Of The Poop Emoji (Or, How Google Brought Poop To America)", Fast Company, November 18, 2014

- Darlin, Damon (March 7, 2015), "America Needs its own Emojis", The New York Times

External links

| Look up feces or faeces in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Feces. |