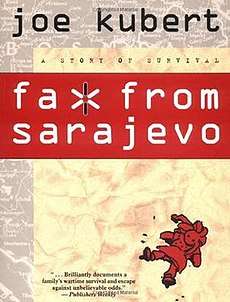

Fax from Sarajevo

Fax from Sarajevo: A Story of Survival is a nonfiction graphic novel by veteran American comic book artist Joe Kubert, published in 1996 by Dark Horse Comics.

| |

| Editor | Bob Cooper |

|---|---|

| Author | Joe Kubert |

| Illustrator | Joe Kubert |

| Cover artist | Joe Kubert |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Siege of Sarajevo, Bosnian War |

| Genre | Comics, memoir |

| Publisher | Dark Horse Comics |

Publication date | November 1996 |

| Media type | Print, paperback |

| Pages | 207 (hardcover) 224 (paperback) |

| ISBN | 1-56971-346-4 |

The book originated as a series of faxes from European comics agent Ervin Rustemagić during the Serbian siege of Sarajevo in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Rustemagić and his family, whose home and possessions in the suburb of Dobrinja were destroyed, spent one-and-a-half years trapped in Sarajevo, communicating with the outside world via fax when they could.

Friend and client Kubert, the highly regarded artist of DC Comics' Sgt. Rock, Hawkman, and many other titles, was one recipient. Collaborating long-distance, they collected Rustemagić's account of life during wartime, with Kubert turning the raw faxes into a somber comics tale that won both of the comics industry's two major accolades, the Eisner Award and the Harvey Award.

Publication history

Fax from Sarajevo was initially released as a 207-page hardcover book[1] and two years later as a 224-page trade paperback.[2]

The book is augmented with transcripts of the faxes sent by Rustemagić, as well those by his associates in the American and European comics industry. In addition, many photos of war-torn Sarajevo, taken by Karim Zaimović (who was later killed by a grenade)[3] are included in the book.

Plot summary

With the beginning of the Bosnian War in early 1992, Ervin Rustemagić, his wife Edina, and children Maja and Edvin have just returned to their home in the Sarajevo suburb of Ilidža after an extended trip to the Netherlands.

By April the city is under siege — the Serbs have closed the roads and are killing anyone who tries to escape the Sarajevo area. With he and his family spending every day terrified of the shelling, and often hiding in their basement to avoid the bombs, Rustemagić has to debate the safety of taking his son to the hospital to deal with his high fever.

Shortly thereafter, a Serbian tank rumbles through their neighborhood — Rustemagić's home and the SAF offices are destroyed. More than 14,000 pieces of original art were lost in the flames. Barely escaping with the clothes on their backs, Rustemagić and his family first find shelter in a half-destroyed building. The next day they find shelter in an apartment building in Dobrinja.

Over the months that follow the Rustemagićs are reduced to living in near-primitive conditions. Broken water pipes lead to days standing in line hoping to fill plastic jugs with water rations. Electricity and cooking fuel are scarce, and children trying scavenge for fuel are the targets of Serbian snipers (who are promised a cash bonus for every kill).

A Rustemagić family's friend escapee from a rape camp, making her way to the family's' shelter to tell the horrors of her experience.

In June 1992, Ervin tries to gain permission to leave the country from the French consulate; each time he visits their offices he must drive a dangerous route from Dobrinja to Sarajevo in his Opel Kadett, protected from live fire only by metal plates attached to the car and piles of comic books, meant to absorb the force of a bullet.

Some months later, in October 1992, the family moves locations to the Sarajevo Holiday Inn, at that point mostly occupied by foreign journalists and constantly under fire.

Thanks to help from European publishers and artists, in late 1993 Rustemagić gains accreditation as a journalist, enabling him to escape Bosnia and Herzegovina. After more than a month fruitlessly attempting to get his family out of the country, he is given Slovenian citizenship, which immediately transfers to his family.

In September 1993, after a tense moment at the airport, Edina, Maja, and Edvin are allowed to fly out of Sarajevo. The entire family is reunited in Split, Croatia.

Awards

Fax From Sarajevo was named the best graphic novel of the year by The Washington Times. The book won the 1996 Don Thompson Award for Best Nonfiction Work. It won the 1997 Harvey Award for Best Graphic Album of Original Work, and the 1997 Eisner Award for Best New Graphic Album. It won two Le Prix France Awards: the 1998 Alph-Art Award for Best Foreign Book Published in France,[4] and the INFO Award for Best Non-Fiction Book Published in France. In addition, Fax From Sarajevo was nominated for the 1997 Firecracker Alternative Book Award.[5]

See also

References

- Dark Horse Comics (November 1996), ISBN 1-56971-143-7

- Dark Horse Comics (October 1998) ISBN 1-56971-346-4

- Kubert, Joe. "This book is dedicated to Karim Zaimovic," Fax From Sarajevo: A Story of Survival softcover (Dark Horse Comics, 1996/1998).

- "Awards of the 1998 Angoulême International Comics Festival," Hahn Library. Accessed Apr. 10, 2014.

- "Miscellaneous Non-Industry Awards Which Have Been Given to Comic Books and/or Comic Book Creators For Their Comic Book Work," Hahn Library. Accessed Apr. 10, 2014.