Fast of Nineveh

In Syriac Christianity, the Fast of Nineveh (Classical Syriac: ܒܥܘܬܐ ܕܢܝܢܘܝ̈ܐ Bā'ūṯā d-Nīnwāyē, literally "Petition of the Ninevites") is a three-day fast starting the third Monday before Clean Monday from Sunday Midnight to Wednesday noon during which participants abstain from all kinds of dairy foods and meat products. However, some parishioners abstain from food and drink altogether from Sunday midnight to Wednesday after Holy Qurbono, which is celebrated before noon. The three day fast of Nineveh commemorates the three days that Prophet Jonah spent inside the belly of the Great Fish and the subsequent fast and repentance of the Ninevites at the warning message of the prophet Jonah according to the bible. (Book of Jonah in the Bible). [2] Marutha of Tikrit is known to have imposed the Fast of Nineveh, and served as Maphrian of the Syriac Orthodox Church until his death on 2 May 649.[3]

| Fast of the Ninevites ܒܥܘܬܐ ܕܢܝܢܘܝ̈ܐ | |

|---|---|

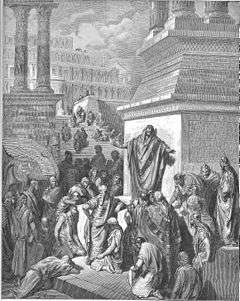

Jonah preaches to the Ninevites | |

| Official name | ܒܥܘܬܐ ܕܢܝܢܘܝܐ |

| Observed by | Church of the East Chaldean Catholic Church Syriac Christian Churches Oriental Orthodox Churches Syro-Malankara Catholic Church Mar Thoma Syrian Church |

| Type | Christian |

| Begins | Monday of the third week before Lent |

| 2020 date | 03-05 February (Assyrian Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church) 10-12 February [1] |

| Frequency | Annual |

History

Jonah appears in 2 Kings aka 4 Kings and is therefore thought to have been active around 786–746 BC.[4] A possible scenario which facilitated the acceptance of Jonah's preaching to the Ninevites is that the reign of Ashur-dan III saw a plague break out in 765 BC, revolt from 763-759 BC and another plague at the end of the revolt. These documented events suggest that Jonah's words were given credibility and adhered to, with everyone allegedly cutting off from food and drinks, including animals and children.[5]

As the patriarch Joseph (Classical Syriac: ܝܘܣܦ) had been deposed, Ezekiel (Classical Syriac: ܚܙܩܝܐܝܠ) had been selected to replace him, much to the joy of the king Khusrow Anushirwan who loved him and held him in high esteem.[6] A mighty plague devastated Mesopotamia with the Sassanian authorities unable to curb its spread and the dead littered the streets, in particular the imperial capital Seleucia-Ctesiphon (Classical Syriac: ܣܠܝܩ ܩܛܝܣܦܘܢ) The metropolitans of Adiabene (Classical Syriac: ܚܕܝܒ "Ḥdāyaḇ", encompassing Arbil, Nineveh, Hakkari and Adhorbayjan) and Beth Garmai (Classical Syriac: ܒܝܬ ܓܪ̈ܡܝ "Bēṯ Garmai", encompassing Kirkuk and the surrounding region) called for services of prayer, fasting and penitence to be held in all the churches under their jurisdiction, as was believed to have been done by the Ninevites following the preaching of the prophet Jonah. Following its success, the tradition has been strictly adhered to every year by the members of the Church of the East. Patriarchs of the Church of the East and Chaldean Catholic Church also called for extra fasts in an effort to alleviate the suffering and affliction of those persecuted by ISIS in the region of Nineveh and the rest of the Middle East.[7]

References

- http://suscopts.org/coptic-orthodox/fasts-and-feasts/2019/

- "Three Day Fast of Nineveh". Syrian Orthodox Church (retrieved from the Internet Archive). Archived from the original on 2011-02-13.

- Barsoum, Ignatius Aphrem I (2003). Matti Moosa, ed. The Scattered Pearls: The History of Syriac Literature and Sciences/1.jpg

- 2 Kings 14:25

- Boardman, John (1982). The Cambridge Ancient History Vol. III Part I: The Prehistory of the Balkans, the Middle East and the Aegean World, Tenth to Eighth Centuries BC. Cambridge University Press. p. 276. ISBN 978-0521224963. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- Chronicle of Seert, ii. 100–101

- Wilmshurst 2011, p. 59