Farrandsville, Pennsylvania

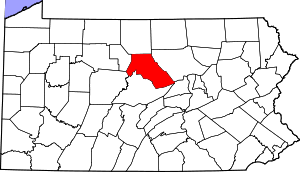

Farrandsville is an unincorporated community in Colebrook Township in Clinton County in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. It is on the north side of the West Branch Susquehanna River about 4 miles (6 km) upstream from Lock Haven at the north end of Farrandsville Road.[2] Whisky Run and Lick Run flow through Farrandsville.[3]

Farrandsville, Pennsylvania | |

|---|---|

Unincorporated community | |

The Farrandsville Furnace in 2012 | |

Farrandsville | |

| Coordinates: 41°10′30″N 77°30′45″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| County | Clinton |

| Township | Colebrook |

| Elevation | 587 ft (179 m) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP | 17745 |

| Area code(s) | 570 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1192450 [1] |

History

The community was named for William P. Farrand,[4] a representative of the Lycoming Coal Company. He founded the village in 1832.[5] Two years later, the West Branch Canal was completed to Farrandsville, giving the village access to supplies and markets by canal boat.[6] The village became the northern terminus of the canal, which was never extended further upstream.[7] During this era, a steamboat named Farrand operated on the West Branch Susquehanna River on the pool of water behind the Dunnstown Dam at Lock Haven. It made regular trips as far upstream as Farrandsville.[8]

In 1836, a group of investors from Boston financed construction of a blast furnace at the village site. Completed in 1837, the Farrandsville Iron Furnace, 43 feet (13 m) square at the base and 54 feet (16 m) high, was one of the largest such furnaces in the United States. Coke made from bituminous coal from a nearby mine fueled the furnace, which used hot blast technology that was new at the time. The furnace produced 50 short tons (45 t) of iron a week, second only to the Lonaconing Furnace in Maryland.[6]

Although supplied with local coal, the furnace was more than 100 miles (160 km) by canal from the nearest iron ore, in Columbia County. The cost of obtaining ore as well as limestone needed during the smelting process was high. This cost, combined with lower income during the Panic of 1837, led to closure of the furnace in 1838.[6]

Despite the furnace shutdown, other industries thrived in Farrandsville through the first decades of the 20th century. Businesses included a fire brick company, a cigar company, and lumber mills. Harbison-Walker Refractories Company of Pittsburgh bought the brickworks in 1902 and continued operations there until 1925. In 1951, the company gave the iron furnace to the Clinton County Historical Society.[6]

References

- "Farrandsville". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. August 2, 1979. Retrieved October 4, 2012.

- Pennsylvania Atlas & Gazetteer. Yarmouth, Maine: DeLorme. 2009. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-89933-280-2.

- United States Geological Survey. "United States Topographic Map". TopoQuest. Retrieved October 4, 2012..

- Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 124.

- "History of the Farrandsville Iron Furnace". Clinton County Genealogical Society. Retrieved October 4, 2012.

- Reed, Diane B. (March 15, 1991). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Farrandsville Iron Furnace" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 8, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2012.

- Shank, William H. (1986) [1981]. The Amazing Pennsylvania Canals (150th Anniversary Edition). York, Pennsylvania: The American Canal and Transportation Center. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0-933788-37-1.

- Miller, Isabel Winner (1966). Old Town: A History of Early Lock Haven. Lock Haven, Pennsylvania: The Annie Halenbake Ross Library. pp. 44–45. OCLC 7151032.