Faraghina

The Faraghina (Arabic: الفراغنة al-Farāghinah, definite plural of فرغاني Farghānī, "inhabitant of Farghanah") were a regiment in the regular army of the Abbasid Caliphate which was active during the ninth century A.D. Consisting of troops who originated from the region of Farghana in Transoxiana, the Faraghina participated in several military campaigns and played a significant role in the politics of the central government, especially during the Anarchy at Samarra.

Background

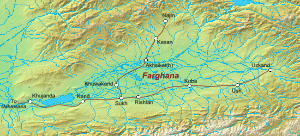

Farghana was a frontier province bordering the lands of Islam during the Umayyad and early Abbasid caliphates. Occupying the entire valley to the east of Khujand, it was surrounded to the north, east and south by mountains, with the Syr Darya running through it. The capital of the region was for some time at Kasan in the north; by the Islamic period, however, it had moved to the city of Akhsikath on the bank of the Syr Darya.[1]

Prior to the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana, control of Farghana is described variously in the sources as having been exercised by an Iranian dynasty whose rulers used the title of ikhshid, or by the local Turks in the region.[2] Farghana was occupied in 712-3 by Qutayba ibn Muslim, but a firm Muslim presence was not established and the local rulers maintained their hold over the country. Over the course of the eighth century the Muslims repeatedly conducted raids into the valley, but its conquest remained incomplete. It was only during the governorship of Nuh ibn Asad in c. 820-1 that Farghana was more fully incorporated into the Islamic state,[3] and it may have been around this same time that the Faraghina regiment began to be formed.[4]

Foundation

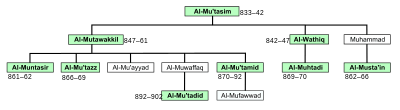

According to the historian al-Mas'udi, the Faraghina regiment was created by al-Mu'tasim (r. 833–842);[5] it seems likely, however, that the process of recruiting soldiers from Farghana was begun during the reign of al-Ma'mun (r. 813-833). Al-Baladhuri, writing in the late ninth century, recorded that al-Ma'mun sent envoys to recruit men from the people of Transoxiana; after his death, his successor al-Mu'tasim continued this policy to such an extent that Transoxianans soon achieved a dominant role in the caliph's army.[6]

The Faraghina were firmly established by the time that al-Mu'tasim decided to construct the new capital of Samarra, and they were given land grants in the city after its completion in 836. According to al-Ya'qubi, the Faraghina were granted allotments adjacent to, but separate from, the quarters of the Turkish soldiers, and that both the Turks and Faraghina were segregated from the general population.[7] The residences of the Faraghina were principally located along the avenues called Shari' al-Barghamish al-Turki and Shari' al-Askar, although some of the regiment officers had allotments along the Shari' al-Hayr al-Jadid.[8]

The Faraghina were only one of several new regiments in al-Mu'tasim's army, serving alongside others such as the Turks, Ushrusaniyya and Maghariba. Of the non-Turkish units, they appear to have been among the largest, and are mentioned relatively frequently in the sources.[9] Al-Ya'qubi referred to at least some of the Faraghina as 'ajam,[10] a term which has been variously interpreted to mean that may have been non-Muslims,[11] non-Arabic speaking[12] or uncivilized.[13] In any case, it seems that they were considered as outsiders by the mainstream elements of Muslim society.[14]

History

The Faraghina are mentioned by al-Tabari as having participated in some of the military campaigns undertaken during al-Mu'tasim's caliphate. They served, for example, under the prominent general al-Afshin in the war against the rebel Babak al-Khurrami in Adharbayjan; during the attack against Babak's fortress of al-Badhdh in 837, they distinguished themselves in battle and played a major part in the capture of the stronghold.[15]

In the following year, during al-Mu'tasim's expedition against Amorium, the Farghanan commander Amr al-Farghani was a leading officer in the caliph's army.[16] While the campaign was underway, however, several Faraghina officers became involved in a plot to kill al-Mu'tasim and replace him with al-'Abbas ibn al-Ma'mun; when the plan was discovered by the caliph, the conspirators, including 'Amr, were rounded up and executed.[17]

Following the assassination of the caliph al-Mutawakkil in December 861, the Faraghina played an important role during the period known as the Anarchy at Samarra (861–870). In the chaotic years following al-Mutawakkil's death, they frequently participated in the riots that broke out in the capital, and they were said to have been involved in the deaths of the wazir Utamish[18] and the Turkish commanders Wasif al-Turki[19] and Salih ibn Wasif.[20] Like the other regiments in Samarra, their main concern during this period was to ensure that they received their pay, as the government was often incapable of providing their salaries in a timely manner.[21]

When civil war broke out between the rival caliphs al-Musta'in and al-Mu'tazz in 865, the Faraghina largely supported the latter.[22] Five thousand Turks and Faraghina were part of the initial force sent from Samarra to besiege al-Musta'in in Baghdad,[23] and over the course of the war additional Farghanan soldiers were sent to join the fight.[24] Some of the Faraghina did initially fight for al-Musta'in, such as those under Muzahim ibn Khaqan, but they later joined Muzahim when he decided to defect to al-Mu'tazz's side.[25]

After the end of the war, from which al-Mu'tazz emerged victorious, the Faraghina returned to Samarra. As the government continued to suffer from a worsening fiscal crisis, the caliph attempted to favor the Faraghina and Maghariba and use them against the Turks;[26] in spite of this, however, all three groups united to overthrow al-Mu'tazz in July 869.[27] The next caliph, al-Muhtadi, likewise promised to bestow favors upon the Faraghina and the other non-Turkish regiments of the army. When the Turks under Musa ibn Bugha al-Kabir revolted against the caliph in June 870, the Faraghina defended al-Muhtadi and comprised the bulk of his cavalry; in the resulting battle, they were defeated and suffered heavy losses.[28]

It is likely that the Faraghina's importance declined after the death of al-Muhtadi and the accession of al-Mu'tamid (r. 870-892). Al-Mu'tamid's brother Abu Ahmad al-Muwaffaq, who became the commander-in-chief of the army, enjoyed strong relations with the Turkish commanders, and he may have preferred the Turks to the exclusion of the Faraghina and other non-Turkish units. After this point, individual Farghanans continued to serve in the army, but the regiment itself largely disappears in the sources.[29]

Notes

- Barthold, pp. 790-91

- Marshak, p. 274; Barthold, p. 790

- Bosworth, p. 253; Barthold, pp. 790-91

- Kennedy, p. 125

- Al-Mas'udi, v. 7: p. 118. See also Ibn al-Athir, v. 6: p. 452

- Al-Baladhuri, p. 205

- Kennedy, p. 119; Gordon, p. 59; al-Ya'qubi, pp. 258-59

- Northedge, p. 170; al-Ya'qubi, pp. 262-63

- Gordon, p. 37; Kennedy, p. 127

- Al-Ya'qubi, p. 258

- Kennedy, pp. 124-25

- Northedge, p. 99

- Gordon, p. 195 n. 71

- Gordon, p. 60

- Al-Tabari, v. 33: pp. 68-69, 71

- Al-Tabari, v. 33: pp. 96, 109, 112

- Al-Tabari, v. 33: pp. 130, 133

- Al-Tabari, v. 35: pp. 12-13

- Al-Mas'udi, v. 7: p. 396; al-Tabari, v. 35: p. 146

- Al-Tabari, v. 36: p. 70

- Al-Tabari, v. 35: p. 146; v. 36: p. 107

- Al-Mas'udi, v. 7: pp. 364-65

- Al-Tabari, v. 35: p. 43

- Al-Tabari, v. 35: p. 48

- Al-Tabari, v. 35: pp. 89-90

- Al-Mas'udi, v. 7: p 397

- Al-Tabari, v. 35: p. 164

- Al-Mas'udi, v. 8: pp. 8-9; al-Tabari, v. 36: pp. 91 ff.

- Kennedy, p. 150; al-Tabari, v. 37: pp. 17, 71, 81

References

- Al-Baladhuri, Ahmad ibn Jabir. The Origins of the Islamic State, Part II. Trans. Francis Clark Murgotten. New York: Columbia University, 1924.

- Barthold, W. & Spuler, B. (1965). "Farghana". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. OCLC 495469475.

- Bosworth, C. Edmund. "Fargana." Encyclopaedia Iranica, Volume IX. Ed. Ehsan Yarshater. New York: Bibliotheca Persica Press, 1999. ISBN 0-933273-35-5

- Gordon, Matthew S. (2001). The Breaking of a Thousand Swords: A History of the Turkish Military of Samarra (A.H. 200–275/815–889 C.E.). Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-4795-2.

- Ibn al-Athir, 'Izz al-Din. Al-Kamil fi al-Tarikh. 6th ed. Beirut: Dar Sader, 1995.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2001). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25093-5.

- Marshak, B.I., and N.N. Negmatov. "Sogdiana." History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III: The Crossroads of Civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Eds. B.A. Litvinsky, Zhang Guang-da and R. Shabani Samghabadi. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, 1996. ISBN 92-3-103211-9

- Al-Mas'udi, Ali ibn al-Husain. Les Prairies D'Or. Ed. and Trans. Charles Barbier de Meynard and Abel Pavet de Courteille. 9 vols. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1861-1917.

- Northedge, Alastair. The Historical Topography of Samarra. London: The British School of Archeology in Iraq, 2005. ISBN 0-903472-17-1

- Yarshater, Ehsan, ed. (1985–2007). The History of al-Ṭabarī (40 vols). SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-7249-1.

- Al-Ya'qubi, Ahmad ibn Abu Ya'qub. Kitab al-Buldan. Ed. M.J. de Goeje. 2nd ed. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1892.