Salih ibn Wasif

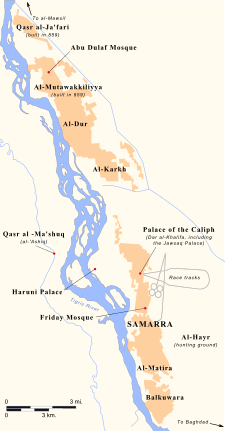

Salih ibn Wasif (Arabic: صالح بن وصيف; died January 29, 870[1]) was a Turkic officer in the service of the Abbasid Caliphate. The son of Wasif, a central figure during the Anarchy at Samarra, Salih briefly seized power in the capital Samarra and deposed the caliph al-Mu'tazz in 869, but he was later defeated by the general Musa ibn Bugha and killed in the following year.

Early career

Salih was the son of Wasif al-Turki, a Turkish general who had risen to prominence during the caliphate of al-Mu'tasim (r. 833–842). Together with his ally, the fellow Turk Bugha al-Sharabi, Wasif had been involved in the assassination of al-Mutawakkil (r. 847–861). During the chaotic period that followed al-Mutawakkil's death (the Anarchy at Samarra, 861–870), Wasif and Bugha were among the principal figures in the events that transpired. They held a strong degree of influence over the central government and were responsible for the downfall of several caliphs and other prominent figures.[2]

Prior to the death of Wasif in 868, Salih appears to have primarily served under his father, although references to him before 867 are few.[3] According to al-Tabari, he played an indirect role in the assassination of the caliph al-Mutawakkil (r. 847–861), when he was one of five sons sent by Wasif to aid the conspirators.[4] In 865, he followed Wasif, Bugha al-Sharabi and al-Musta'in (r. 862–866) in their flight from Samarra to Baghdad, and toward the end of the civil war in 865–866 between al-Musta'in and al-Mu'tazz (r. 866–869), he was put in charge of the Shammasiyyah Gate on the eastern side of the city.[5]

The killing of Wasif by rioting troops in Samarra around the end of October 867 initially left his family in a tenuous position; his official duties were given to his old ally Bugha, and a mob unsuccessfully attempted to plunder his and his sons' residences.[6] At this point, however, Salih assumed the leadership of the Wasif clan and secured the loyalty of his followers. With this network of supporters behind him, he quickly gained the influence that his father had previously held.[7] His rise in status was soon followed by government appointments, and he was given the administration of the districts of Diyar Mudar, Qinnasrin and the 'Awasim, to which he appointed Abi'l-Saj Devdad as his resident governor in early 868.[8]

In 868, following a breakdown in relations between the caliph al-Mu'tazz and Bugha, both men attempted to gain Salih's favor. In November of that year Salih married Bugha's daughter Jum'ah;[9] at the same time, however, he was patronized by al-Mu'tazz, who was attempting to build a coalition against Bugha.[10] Soon after Salih's marriage, Bugha decided to flee from Samarra; he later attempted to seek refuge with Salih, but was caught and executed on al-Mu'tazz's orders.[11]

Seizure of power

By early 869, with the central government continually paralyzed by revenue shortfalls and disorders in Samarra, Salih decided to seize control of affairs in the capital. His first move was to act against the leaders of the caliphal bureaucracy, who were among the chief rivals of the Turks.[12] On May 19, 869, he came to al-Mu'tazz and began to make complaints about the vizier Ahmad ibn Isra'il, accusing him of bankrupting the state treasury and failing to pay the salaries of the troops. Ahmad, who was present, attempted to counter the charges, and a heated argument between the two broke out. Salih's followers suddenly burst into the room with swords drawn, and seized Ahmad and the secretaries al-Hasan ibn Makhlad and Abu Nuh 'Isa ibn Ibrahim, who collectively headed the caliph's administration. Al-Mu'tazz attempted to intercede with Salih on their behalf, but in vain; the three bureaucrats were beaten, incarcerated at Salih's residence and pronounced as traitors. They were eventually forced to agree to make a series of large payments, while the Turks seized their estates and those of their relatives.[13]

Having purged the heads of the administration, Salih now effectively took over the government, and decrees were issued in his name as if he had the title of vizier.[14] The Turks, however, still failed to receive their pay, and they soon shifted the blame to al-Mu'tazz himself. With the treasury empty and the caliph unable to meet the demands of the troops, the regiments in Samarra became united in their decision to depose him. On July 11, 869, Salih and two other Turkish officers, Bayakbak and Muhammad ibn Bugha, entered the caliphal palace with their weapons and demanded that al-Mu'tazz come out; when the latter refused, their lieutenants entered and seized him. The caliph was forced to sign a letter of deposition, and after suffering maltreatment at the hands of the Turks, he died on July 16.[15]

The caliphate now entered into the hands of al-Muhtadi, but power continued to be exercised by Salih.[16] The new administration immediately ran into problems; the central government continued to suffer from revenue shortages and the Turkish soldiers were demanding their pay. In order to resolve these issues, Salih decided to expropriate the assets of the former members of al-Mu'tazz's regime until the necessary funds were raised. He first targeted al-Mu'tazz's mother Qabihah, who was found and forced to surrender a large amount of money and valuables that she had hidden away.[17] A short time later, Salih again turned to the bureaucrats Ahmad ibn Isra'il, Ibn Makhlad and Abu Nuh and subjected them to a fresh round of torture, in an attempt to extract more wealth from them. The torture was carried out despite the opposition of al-Muhtadi, who made no public move against Salih. On September 8, Ahmad and Abu Nuh were publicly flogged and paraded around Samarra, and both men died from their wounds that same day; Ibn Makhlad was spared but remained imprisoned.[18]

Downfall and death

Salih's assumption of power in Samarra soon earned him the enmity of several rivals, among the most prominent of which was the Turkish general Musa ibn Bugha. Musa and his lieutenant Muflih had been conducting military operations against rebels in the Jibal and Tabaristan since 867, but upon learning of al-Mu'tazz's deposition and death, along with the state of affairs in Samarra, they decided to abandon their campaign and return to the capital to oppose Salih.[19]

Salih, realizing that Musa's arrival posed a serious threat to him, attempted to convince al-Muhatdi that Musa's actions were treasonous. The caliph, for his part, wrote to Musa and urged him to return to the campaign against the rebels, but Musa simply ignored these requests and continued his approach.[20] He and his army arrived on December 19, 869; almost immediately, he had al-Muhtadi brought before him, and received a promise from the caliph that he would not side with Salih against him or his supporters. At the same time, Salih gathered some five thousand troops that were loyal to him; these, however, were not prepared to face Musa, and the majority of them gradually departed until only eight hundred were left. When Salih learned that most of his forces had abandoned him, he gave up hope of directly confronting Musa and decided to go into hiding instead.[21]

The situation in Samarra was now extremely volatile. Salih, who remained in hiding, sent a letter in which he attempted to justify his actions over the course of the last year, and al-Muhtadi urged Musa and his followers (which now included Bayakbak and Muhammad ibn Bugha) to make peace. This only caused Musa and his fellow officers to suspect that al-Muhtadi was secretly working with Salih to eliminate them, and they began to discuss the possibility about forcing the caliph to abdicate. Salih and the caliph, however, both still had supporters in the army, who threatened to kill Musa and his allies if al-Muhtadi was harmed. With no one having a clear advantage, the caliph and the various factions in the army began a series of negotiations, and on January 13, 870, a tentative agreement was reached, whereby Musa, Salih and Bayakbak would all be restored to their former positions and would share power with each other. As part of the reconciliation, a guarantee of safe conduct was issued for Salih to come out of hiding.[23]

Chances for peace between the two factions, however, were short-lived. On January 14, forces loyal to Salih assembled in the capital and began to act in a belligerent manner; Musa immediately responded by deploying his own troops and marched toward the palace of the caliph. Upon his arrival, a proclamation was issued demanding that all of Salih's family, commanders, and supporters present themselves at the palace; anyone who failed to do so by the next day would have their names eliminated from the payrolls and their houses would be destroyed, and they would be subjected to flogging and imprisonment. The search to find Salih was then intensified and raids were conducted on the houses of anyone suspected of harboring him.[24]

After several more days of searching, Salih's location was finally discovered, and a group of men were dispatched to capture him. The sources disagree on what happened next, but the end result was that Salih was killed. According to al-Mas'udi, he was either killed while fighting against the agents attempting to arrest him, after which his head was brought to Musa, or he was captured and subjected to the same punishment that he had inflicted on al-Mu'tazz, by being locked in a burning oven until he died.[25] Al-Tabari claims that Salih was captured and taken, under armed escort, to Musa's residence, and from there he was to be brought to the palace of the caliph. On the way there, however, one of Muflih's soldiers struck him from behind, and he was then decapitated. His head was first brought to al-Muhtadi, after which it was carried around Samarra on a lance with the proclamation "This is the recompense for slaying one's master," in reference to the death of al-Mu'tazz. From there his head was briefly put on public display, before it was finally given to his family for burial.[26]

Notes

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 36: p. 90

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 157, 168–72

- Gordon 2001, p. 97

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 34: p. 180

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 35: p. 102

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 35: p. 146

- Al-Ya'qubi 1883, p. 614; Al-Mas'udi 1861–1877, v. 7: p. 396; Gordon 2001, pp. 97–98, 114

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 35: p. 154

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 35: p. 152

- Al-Ya'qubi 1883, p. 615

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 35: pp. 152–54; Gordon 2001, p. 98

- Kennedy 2004, p. 170; Sourdel 1959, p. 295

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 35: pp. 161–63; Al-Ya'qubi 1883, p. 616; Gordon 2001, p. 100

- Al-Mas'udi 1861–1877, v. 7: p. 379; Sourdel 1959, pp. 295–298

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 35: pp. 163–65; Al-Mas'udi 1861–1877, v. 7: p. 397; Gordon 2001, p. 101

- Sourdel 1959, pp. 299–300

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 36: pp. 5–9; Gordon 2001, p. 101

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 36: pp. 9–13; Al-Ya'qubi 1883, p. 617; Gordon 2001, pp. 101–02

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 36: pp. 24–26; Al-Mas'udi 1861–1877, v. 8: p. 3; Gordon 2001, p. 102

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 36: pp. 27–29

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 36: pp. 68–71; Al-Mas'udi 1861–1877, v. 8: p. 5; Gordon 2001, p. 102

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 36: p. 89

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 36: pp. 72-86; Gordon 2001, p. 102

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 36: pp. 86–88; Gordon 2001, p. 103

- Al-Mas'udi 1861–1877, v. 8: pp. 7–8

- Yarshater 1985–2007, v. 36: pp. 88–90; Gordon 2001, p. 103

References

- Gordon, Matthew S. (2001). The Breaking of a Thousand Swords: A History of the Turkish Military of Samarra (A.H. 200–275/815–889 C.E.). Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-4795-2.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Al-Mas'udi, Ali ibn al-Husain (1861–1877). Les Prairies D'Or. 9 vols. Ed. and Trans. Charles Barbier de Meynard and Abel Pavet de Courteille. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sourdel, Dominique (1959). Le Vizirat Abbaside de 749 à 936 (132 à 224 de l'Hégire) Vol. I. Damascus: Institut Français de Damas.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yarshater, Ehsan, ed. (1985–2007). The History of al-Ṭabarī (40 vols). SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-7249-1.

- Al-Ya'qubi, Ahmad ibn Abu Ya'qub (1883). Houtsma, M. Th. (ed.). Historiae, Vol. 2. Leiden: E. J. Brill.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)