Faidherbia

Faidherbia is a genus of leguminous plants containing one species, Faidherbia albida, which was formerly widely included in the genus Acacia as Acacia albida. The species is native to Africa and the Middle East and has also been introduced to Pakistan and India.[3] Common names include apple-ring acacia[4] (their circular, indehiscent seed pods resemble apple rings),[5] and winter thorn.[3] The South African name is ana tree.[3][6]

| Faidherbia | |

|---|---|

| F. albida growing with palms and maize crops | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Genus: | Faidherbia |

| Species: | F. albida |

| Binomial name | |

| Faidherbia albida | |

| |

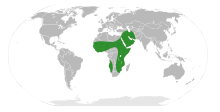

| The range of Faidherbia albida. | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Taxonomy

This species has been known as Acacia albida for a long time, and is often still known as such. Guinet (1969) in Pondicherry first proposed separating it into the genus Faidherbia, a genus erected the previous century by Auguste Chevalier with this as the type species, seconded by the South African James Henderson Ross (1973) and the Senegalese legume botanist Nongonierma (1976, 1978),[7] but authors continued to favour classification under Acacia as of 1997.[6][7]

Infraspecific variability

According to John Patrick Micklethwait Brenan writing in the Flora of Tropical East Africa (1959), two forms can be distinguished in this region (Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda), race A is distinguished by generally smooth features, whereas race B is more hairy. Ross (1979) notes all trees in the south of central Tanzania belong to race B.[8] Similarly, Nongonierma described two forms for Senegal, var. glabra and var. pseudoglabra, but his distinction is disregarded taxonomically as of 2007.[2]

Description

It is a thorny tree growing up 6–30 m (20–98 ft) tall and 2 m (6.6 ft) in trunk diameter. Its deep-penetrating tap root makes it highly resistant to drought. The bark is grey, and fissured when old. There are 11,000 seeds/kg.

Distribution

In Southern Africa it is absent throughout most of the territory, avoiding dry and upland areas or areas of winter rainfall, but occurs along the floodplains of the Zambezi and Limpopo, in Kruger National Park, Pongoland, around Gaberone, in the northern Okavango, the Caprivi Strip, Kakaoveld, western Gaza and Maputo Province.[6]

In the rest of Africa it is absent from deserts, areas of high rainfall, tropical rainforests and mountainous areas, but occurs throughout the eastern half of the continent from the southern coast in Maputaland to Egypt, throughout the Subsaharan Sahel and the Horn of Africa. In Northern Africa, besides in Egypt it also occurs in Algeria, it does not occur in Morocco proper, but it is found in Western Sahara.[3]

In Asia it is thought to be native to Yemen and Saudi Arabia in the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, and in the Levant in Israel, Syria and Lebanon.[3]

A population is found in relict groves in Israel (in the Shimron nature reserve, near the community settlement of Timrat). All of the trees in a given grove are genetically identical and seem to have multiplied by vegetative reproduction only, for thousands of years.

Introduced populations are found on Cyprus and Ascension Island, and in Pakistan and Karnataka (India).[3]

Ecology

In Southern Africa it usually grows on alluvial floodplains in bushveld, on riverbanks or flood pans, in swamps, or in dry watercourses that can flood during rains.[6] It grows in woodland in the Sahel, along the Zambezi and in Sudan.[3] In the Sahel it grows gregariously in groves. It grows in savannahs in Sudan and the Sahel, in heavy soils with good drainage.[7]

In tropical eastern Africa it sometimes occurs singly, but may often be the dominant species in dry woodlands.[2] In the Sahel it has an irregular, clumped distribution, absent in some areas but is sometimes locally common.[7]

It grows in areas with 250–600 mm (9.8–23.6 in) of rain per year.[8]

Cultivation and uses

Faidherbia albida is important in the Sahel for raising bees, since its flowers provide bee forage at the close of the rainy season, when most other local plants do not.[9]

The seed pods are used for raising livestock, are used as camel fodder in Nigeria,[9] and are eaten by stock and game in Southern Africa.[6] They are relished by elephant, antelope, buffalo, baboons and various browsers and grazers, though strangely ignored by warthog and zebra.[10]

The wood is used for canoes, mortars, and pestles and the bark is pounded in Nigeria and used as a packing material on pack animals. The wood has a density of about 560 kg/m3 at a water content of 12%.[11] The energy value of the wood as fuel is 19.741 kJ/kg.[9]

Ashes of the wood are used in making soap and as a depilatory and tanning agent for hides. The wood is used for carving; the thorny branches useful for a natural barbed fence.[12] Pods and foliage are highly regarded as livestock fodder. Some 90% of Senegalese farmers interviewed by Felker (1981) collected, stored, and rationed Acacia albida pods to livestock. Zimbabweans use the pods to stupefy fish. Humans eat the boiled seeds in times of scarcity in Zimbabwe.

It is valued in agroforestry as it fixes nitrogen, and a high yield has been achieved in at least one test plot of maize crops grown amongst the trees at a density of 100 to 25 tree per hectare.[13] According to a 2018 article by the Guardian, monocultures of this species are popular in parts of Niger, where it is known as gao in Hausa, to use for intercropping.[14] It is also used for erosion control.

Cultural significance

Faiderbia albida is known in the Bambara language as balanzan and is the official tree of the city of Segou on the Niger River in central Mali.[15] According to legend, Segou is home to 4,444 balanzan trees, plus one mysterious "missing tree" the location of which cannot be identified.

In Serer and some of the Cangin languages, it is called Saas. Saas figures prominently in the creation myth of the Serer people. According to their creation myth, it is the tree of life and fertility.[16]

Conservation

Faidherbia albida is not listed as being a threatened species.

Notes

- The Legume Phylogeny Working Group (LPWG) (2017). "A new subfamily classification of the Leguminosae based on a taxonomically comprehensive phylogeny". Taxon. 66 (1): 44–77. doi:10.12705/661.3.

- African Plants Database: Faidherbia albida Archived 2007-09-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ILDIS LegumeWeb

- C.Michael Hogan, ed. 2010. Faidherbia albida. Encyclopedia of Life.

- Armstrong, W. P. "Unforgettable Acacias, A Large Genus Of Trees & Shrubs". Wayne's Word. Archived from the original on 10 November 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- van Wyk, Braam; van Wyk, Piet (1997). Field Guide to trees of southern Africa. Cape Town: Struik. p. 500. ISBN 1-86825-922-6.

- Geerling, Chris (15 July 1982). "Guide de terrain des ligneux Saheliens et Soudano Guineens". Mededelingen Landbouwhogeschool Wageningen (in French). 82 (3): 177, 178.

- FAO: Handbook on Seeds of Dry-Zone Acacias

- World AgroForestry

- Kevin M. Dunham (1990). "Fruit production by Acacia albida trees in Zambezi riverine woodlands". Journal of Tropical Ecology. 6 (4): 445–457. doi:10.1017/S0266467400004843.

- FAO: Role of acacia species in the rural economy of dry Africa and the Near East

- VITA (1977)

- Bayala, Jules; Larwanou, Mahamane; Kalinganire, Antoine; Mowo, Jeremias G.; Weldesemayat, Sileshi G.; Ajayi, Oluyede C.; Akinnifesi, Festus K.; Garrity, Dennis Philip (2010-09-01). "Evergreen Agriculture: a robust approach to sustainable food security in Africa" (PDF). Food Security. 2 (3): 197–214. doi:10.1007/s12571-010-0070-7. ISSN 1876-4525.

- MacLean, Ruth (2018-08-16). "The great African regreening: Millions of 'magical' new trees bring renewal". The Guardian.

- BBC News story on Mali's Faidherbia albida trees

- (in French) Gravrand, Henry, "La civilisation sereer", vol. II : Pangool, Nouvelles éditions africaines, Dakar, 1990, pp. 125–127, ISBN 2-7236-1055-1

References

- Edmund G.C.Barrow. 1996. The Drylands of Africa:Local Participation in Tree Management. Initiatives Publishers: Nairobi, Kenya.

- A.E.G.Storrs. 1979. Know Your Trees: Some Common Trees Found in Zambia. Government Republic of Zambia, Forestry Department: Ndola, Zambia.

- Africa: Forestry, Agroforestry and Environment

- Hawaiian Ecosystems at Risk project (HEAR)

- Purdue University New Crop Resource Online Program

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Faidherbia albida |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Faidherbia albida. |

- Faidherbia albida in West African plants – A Photo Guide.

- "Faidherbia albida". PlantZAfrica.com. Retrieved 2010-02-09.