Fahr Convent

Fahr Convent, (German: Kloster Fahr) is a Benedictine convent located in the Swiss municipality of Würenlos in the canton of Aargau. Located in different cantons, Einsiedeln Abbey and Fahr Convent form a double monastery, overseen by the male Abbot of Einsiedeln, no converse arrangement appears to be available for the Abbess of Fahr. Fahr and Einsiedeln may be one of the last of such arrangements to survive.[1]

Kloster Fahr | |

Fahr Convent as seen from the west, Unterengstringen in the background | |

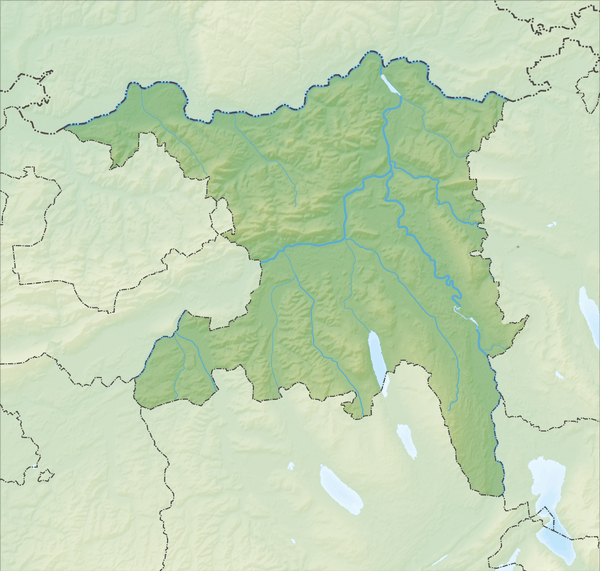

Location within Canton of Aargau  Fahr Convent (Switzerland) | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Order | Order of Saint Benedict |

| Established | 22 January 1130 |

| Mother house | Kloster Einsiedeln |

| Dedicated to | Our Lady |

| Diocese | Roman Catholic Diocese of Basel |

| Controlled churches | 3 |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Judenta and Luitold von Regensberg |

| Abbot | Urban Federer OSB, Kloster Einsiedeln |

| Prior | Irene Gassmann OSB (since 2003) |

| Site | |

| Location | Würenlos, Canton of Aargau, being an enclave within Unterengstringen, Canton of Zürich, Switzerland |

| Coordinates | 47°24′30.42″N 8°26′21.48″E |

| Public access | allowed |

| Other information | extensive agriculture by the nunnery, monastery shop and restaurant |

Geographical and administratively special situation

Historically the convent was located in an exclave of canton Aargau within the municipality of Unterengstringen in the canton of Zürich in the Limmat Valley. The convent had not been part of a political municipality, although some administrative tasks have been carried out by the Würenlos authorities since the 19th century and the nuns were always allowed to fulfill their political rights (voting, etc.) in Würenlos. Since 1 January 2008 Fahr Convent has been a part of Würenlos.[2]

History

The convent is first mentioned in AD 1130 as Vare (an old term used for "ferry"). The lands were donated by the House of Regensberg. On 22 January 1130 Lütold II and his son Lütold III and his wife Judenta[3] handed over lands and estates on the shore of the Limmat around Weiningen and Unterengstringen-Oberengstringen to the Einsiedeln Abbey to establish a Benedictine convent. The Chapel of St. Nicholas already stood on the land. This may have been connected with the death of Lütold I in 1088 while engaged in battle against the forces of the Abbey of Einsiedeln. The convent was dedicated to Our Lady. In addition to the medieval St. Nikolaus-Kapelle (Saint Nicholas chapel), built around 10th century AD and now called St. Anna-Kapelle, and the late medieval church of the convent, the parish church of Weiningen were subordinated to the convent.

From the very beginning, the convent has been overseen by the Abbot of Einsiedeln; the nuns are led in their daily life by a prioress appointed by the abbot. The bailiwick rights were first held by the Regensberg family, after 1306 by the citizens of the municipality of Zürich, and from 1434 to 1798 by the Meyer von Knonau family.

Around 1530 the convent was suppressed during the Reformation in Zürich, but it reopened in 1576. An era of prosperity during the 17th century led to a brisk program of construction: In 1678 the tavern Zu den zwei Raben ("Two Ravens", the emblem of Einsiedeln Abbey) was built; from 1685 to 1696 the cloister and church tower were renovated; in 1703/04 a new refectory was designed by Johann Moosbrugger; and a house for the chaplain was erected in 1730/34. From 1743 to 1746 the convent church was decorated with frescoes by the Torricelli brothers.

In dissolving the old County (Grafschaft) of Baden in 1803, the cantons of Zurich and Aargau established an exclave of Aargau within the canton of Zürich, for the former lands of the convent. Formerly part of the Bishopric of Constance, the convent has been part of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Basel since 1828. The canton of Aargau chose in 1841 to close all monasteries within its territory, but this was reversed in 1843 for convents. The negotiations between Einsiedeln Abbey and the cantonal authorities regarding assets and authority were completed nearly 90 years later, in 1932. At that point Aargau granted full autonomy to the conventual community.

During World War II, from November 1943 to February 1944, 11 female Jewish refugees lived secretly in the cloister; unfortunately they had to leave for an unknown destination when the school was opened.[4]

On 1 February 1944, the convent established a Bäuerinnenschule, i.e. an agricultural school for women.

On 1 January 2008 the convent was incorporated into the municipality of Würenlos, happening over a century after the municipality's initial attempts to absorb the 1.48-hectare area of the convent.[5]

On 22 January 2009 the former Abbot of Einsiedeln, Dom Martin Werlen, O.S.B., presented the nuns with a new community seal, thereby indicating that the nuns were in full control of the business affairs of their convent.[6]

In 2014 the women's agricultural school (Bäuerinnenschule) had to close for financial reasons.[7] At the same time an overall renovation of the convent buildings, erected between 1689 and 1746 was undertaken. The interiors, windows and antiquated power supply were refurbished in 2016 to finally comply with fire prevention and other modern statutory requirements.[8]

Cloister

As of April 2010, there were 26 nuns (7 in 1873, 33 in 2000) living at the convent. Silja Walter (Sister Maria Hedwig, O.S.B.) (1919–2011), a renowned novelist, was the most prominent member of the community.[9][10]

On 23 April 2016 the Silja-Walter-Raum was inaugurated. Sister Maria Hedwig's literary work is inextricably linked to the convent as she lived for over 60 years in the same Benedictine community. During this time, Silja Walter wrote most of her work which included lyrics, mystery plays and theatre. After the renovation, the former office of the provost with its beautiful stucco ceiling was chosen to establish a small museum. It contains numerous texts, film, audio and photographic documents, as well as excerpts from the radio interview from 1982, when Silja Walter and her brother, Otto F. Walter, another renowned Swiss writer, recorded the interview tape Eine Insel (An Island). But also personal objects like the nun's typewriter are exhibited, and also the lesser known drawings and painting of the artist. The monastery would appeal to people who knew the artist's work, but also for the younger generation, said Prioress Irene during an interview.[11] For now, the room will be open every last Sunday of the month after the worship service from approximately 10:45 to 14:00. Admission is free.[12]

On the feast day of Saint Wiborada – the first (Swiss) woman to be canonized by the Roman Catholic Church – 2 May 2016, a two month pilgrimage began from Wiborada's native St. Gallen to Rome made up of eight female town residents and seven Fahr sisters, as part of a Catholic gender equality campaign, Kirche mit*. Along their 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) journey to the Vatican, this group of pilgrims was accompanied in stages by other women's rights activists.[13][14] By mid-May 2016 around 650 people (approximately one fifth men) joined for at least one day's stage, and there are 400 more registrations for the final section of the pilgrimage in Rome.[15] Whether the Pope will grant an audience to the group of pilgrims on 2 July, the day of the Visitation, was uncertain; actually he then should be on vacation.[13]

Cloister garden

Sister Beatrice Beerli (born 1947) and head of horticulture, had responsibility for the multi-award-winning convent gardens for over 20 years. Since the closure of the school in July 2013, she passed on her knowledge to occasional group tours.[16][17]

Current Activities

For centuries viticulture had an important role in convent life. Even in the deed of donation of 22 January 1130, a vineyard was itemised. In the Middle Ages its cultivation and trade in wine was significant and frequently documented. Cultivation and wine production are part of the historic tradition, and the present vineyards comprise 4.2 hectares on "Wingert" hill just above the convent in the canton of Zürich and on convent property in Weiningen where a range of grape varieties are grown .[18] The well-known wine estate is managed by the nuns and around 30 external employees. Other agricultural products are made in the convent including liquors and honey.

The convent's renowned agricultural school for women (Bäuerinnenschule) established in 1944 had to close in 2015 for economic and staffing reasons.[7]

Cultural Heritage

Kloster Fahr is listed in the Swiss inventory of cultural property of national and regional significance as a Class A object of national importance.[19]

Gallery

Church

Church Main altar

Main altar- Fresco on the church ceiling

Cemetery and chapel

Cemetery and chapel Tavern zu den zwei Raben

Tavern zu den zwei Raben- Inn sign showing the two ravens of Einsiedeln Abbey

- Sweetmeats made at the convent

Ferry route to the convent

Ferry route to the convent The former agricultural school in the convent grounds

The former agricultural school in the convent grounds

References

- In fact, there is such an arrangement in England at the Orthodox monastery of Tolleshunt Knights."Doppelkloster". Kloster Fahr (in German). Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- The convent has its own postal code, 8109 Kloster Fahr.

- Martin Leonhard (29 January 2013). "Regensberg, von" (in German). HDS. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- "Das Kloster Fahr nahm jüdische Frauen auf" (in German). Tages Anzeiger. 4 April 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "Kloster Fahr wird eingemeindet" (in German). Tages Anzeiger. 7 July 2011. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- "Kloster Fahr erhält Siegelrecht zurück" (in German). Orden online. 24 January 2009. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- Anina Gepp (25 January 2015). "Grosser Abschied: Kloster Fahr schliesst Bäuerinnenschule" (in German). Limmattaler Zeitung. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- Sophie Rüesch (31 December 2015). "So fällt das Loslassen von der Bäuerinnenschule weniger schwer" (in German). Limmattaler Zeitung. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- "Silja Walter ist tot" (in German). Tages-Anzeiger. 31 January 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "Prior Irene Gassmann, Kloster Fahr: Zum Tod von Schwester Hedwig (Silja) Walter OSB" (in German). kath.ch. 31 January 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- Anna Gepp (25 April 2016). "Unerwartete Einblicke hinter die Klostermauern zu Ehren von Schwester Silja Walter" (in German). Limmattaler Zeitung. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- Sandro Zimmerli (22 April 2016). "Silja-Walter-Raum im Kloster Fahr: So lebte die schreibende Nonne" (in German). Limmattaler Zeitung. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- Sophie Rüesch (6 May 2016). "Tausend Gläubige setzten ein Zeichen für mehr kirchliche Frauenrechte. Mittendrin: die Fahrer Nonnen" (in German). Limmattaler Zeitung. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Courage: Irene Gassmann" (in German). Beobachter. 15 April 2016. Archived from the original on 10 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- "Pilgerprojekt der Nonnen Fahr hat Ziel jetzt schon erreicht" (in German). Limmattaler Zeitung. 17 May 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- Sophie Rüesch (10 June 2016). "Die Nonnen laden in ihre preisgekrönten Gärten ein" (in German). Limmattaler Zeitung. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Bäuerinnenschule Kloster Fahr: Abschied im Blütenmeer" (in German). migrosmagazin.ch. 29 July 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Klösterlicher Weinbau gestern und heute" (in German). Kloster Fahr. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- "A-Objekte KGS-Inventar" (PDF). Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, Amt für Bevölkerungsschutz. 1 January 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

Literature

- Hélène Arnet: Das Kloster Fahr im Mittelalter. Zürich 1995, ISBN 3-85865-511-2.

- Silja Walter: Der Ruf aus dem Garten, Paulus-Verlag, Fribourg 1995, ISBN 3-7228-0370-5.

- Silja Walter: Das Kloster am Rande der Stadt. Verlag die Arche, Zürich 1980, ISBN 3-7160-1685-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fahr Abbey. |

- Official website (in German)

- Necrologium Fahrense at the archives of the Einsiedeln Abbey (in German)

- Fahr in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.