Low German house

The Low German house[1] or Fachhallenhaus is a type of timber-framed farmhouse found in Northern Germany and the Netherlands, which combines living quarters, byre and barn under one roof.[2] It is built as a large hall with bays on the sides for livestock and storage and with the living accommodation at one end.

The Low German house appeared during the 13th to 15th centuries and was referred to as the Low Saxon house (Niedersachsenhaus) in early research works. Until its decline in the 19th century, this rural, agricultural farmhouse style was widely distributed through the North German Plain, all the way from the Lower Rhine to Mecklenburg. Even today, the Fachhallenhaus still characterises the appearance of many north German villages.

Name

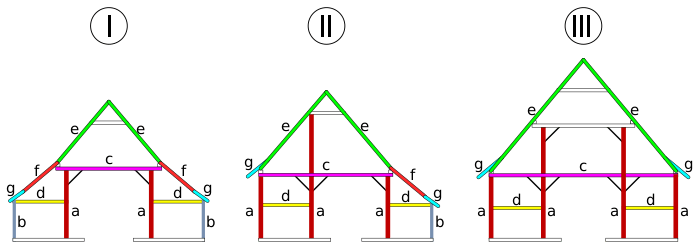

The German name, Fachhallenhaus, is a regional variation of the term Hallenhaus ("hall house", sometimes qualified as the "Low Saxon hall house"). In the academic definition of this type of house the word Fach does not refer to the Fachwerk or "timber-framing" of the walls, but to the large Gefach or "bay" between two pairs of the wooden posts (Ständer) supporting the ceiling of the hall and the roof which are spaced about 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) apart. This was also used as a measure of house size: the smallest only had 2 bays, the largest, with 10 bays, were about 25 metres (82 ft) long. The term Halle ("hall") refers to the large open threshing area or Diele (also Deele or Deel) formed by two rows of posts. The prefix Niederdeutsch ("Low German") refers to the region in which they were mainly found.[1] Because almost all timber-framed and hall-type farmhouses were divided into so-called Fache (bays), the prefix Fach appears superfluous.

The academic name for this type of house comes from the German words "Fach" (bay), describing the space (up to 2.5 metres (8.2 ft)) between trusses made of two rafters fixed to a tie beam and connected to two posts with braces and "Halle", meaning something like hall as in a hall house. The walls were usually timber-framed, made of posts and rails; the panels (Gefache) in between are filled with wattle and daub or bricks. One bay may be two or rarely three Gefache wide.

Alternative names

In the past other names were commonly used for this type of farmhouse, derived either from their design or the region in which they were built:

- Flett-Deelen-Haus (a Hallenhaus) with a very common floorplan including an open kitchen or Flett to the side of the Deele

- Kübbungshaus (Hallenhaus of two-post construction, also called a Zweiständerhaus, named after the non-load-bearing side aisles or Kübbungen)

- Niedersachsenhaus (Low Saxon house)

- Sächsisches Haus (Saxon house)

- Altsächsisches Bauernhaus (Old Saxon farmhouse)

- Westfälisches Bauernhaus (Westphalian farmhouse)

- Westfalenhaus (Westphalian house)

Niedersachsenhaus is the most widespread and commonly used term, even though it is not strictly correct from an academic point of view.

Other terms

Because this type of farm combines living quarters, stalls and hay storage under one roof it is also described as an Einhaus ("single house" or "all-in-one house") and the attached farmyard as an Eindachhof ("single-roofed farmyard"). A special feature of the Low German house is its longitudinal division, also referred to as dreischiffige or "triple-aisled". This is considerably different from all-in-one farmhouses elsewhere in Germany and Europe which are built with traditional transverse divisions, as in the Ernhaus, not to mention other common farm layouts where the farm comprises several buildings with different functions, usually around a farmyard.

Early history

The Low German house first emerged towards the end of the Middle Ages. Only a few years ago a Hallehuis was discovered in the Dutch province of Drenthe, the frame of which can be dated to 1386. In 2012 a "hallehuis" was discovered in Best, in the Dutch provincie of North Brabant, which dates back to 1262 and is still in use as a stable. The living part of the farm itself is built in recent times, in 1640 at the earliest, but probably around 1680. The farm is an official monument.[3] The oldest surviving houses of this type in Germany date to the late 15th century (e.g. in Schwinde, Winsen Elbe Marsh 1494/95). Regional differences arose due to the need to adapt to local farming and climatic conditions. The design also changed over time and was appropriate to its owner's social class. From the outset, and for a long time thereafter, people and animals were accommodated in different areas within a large room. Gradually the living quarters were separated from the working area and animals. The first improvements were separate sleeping quarters for the farmer and his family at the rear of the farmhouse. Sleeping accommodation for farmhands and maids was created above (in Westphalia) or next to (in Lower Saxony and Holstein) the livestock stalls at the sides. Finished linen, destined for sale, was also stored in a special room. As the demand for comfort and status increased, one or more rooms would be heated. Finally the stove was moved into an enclosed kitchen rather than being in a Flett or open hearth at the end of the hall.

Predecessors

The Low German house is similar in construction to the neolithic longhouse, although there is no evidence of a direct connexion. The longhouse first appeared during the period of the Linear Pottery culture about 7,000 years ago and has been discovered during the course of archaeological excavations in widely differing regions across Europe, including the Ville ridge west of Cologne. The longhouse differed from later types of house in that it had a central row of posts under the roof ridge. It was therefore not three- but four-aisled. To start with, cattle were kept outside overnight in Hürden or pens. With the transition of agriculture to permanent fields the cattle were brought into the house, which then became a so-called Wohnstallhaus or byre-dwelling.

Later the centre posts were omitted to form a triple-aisled longhouse (dreischiffigen Langhaus, often a dreischiffigen Wohnstallhaus) that could be found in almost all of northwest Europe in the Early Middle Ages. Its roof structure rested as before on posts set into the ground and was therefore not very durable or weight-bearing. As a result, these houses already had rafters, but no loft to store the harvest. The outer walls were only made of wattle and daub (Flechtwerk).

By the Carolingian era, houses built for the nobility had their wooden, load-bearing posts set on foundations of wood or stone. Such uprights, called Ständer, were very strong and lasted several hundred years. These posts were first used for farmhouses in northern Germany from the 13th century, and enable them to be furnished with a load-bearing loft. In the 15th and 16th centuries the design of the timber-framing was further perfected.

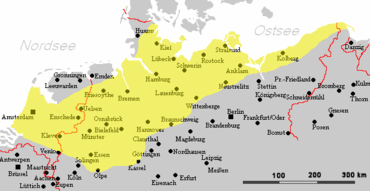

Distribution

The Low German house had a wide distribution across an area almost 1,000 km long which roughly corresponds to the Low German language area. In the west it stretched into parts of the Netherlands where the height of gable and loft are usually lower, mirroring its development over time from self-sufficiency to market-oriented farming.

From the Lower Rhine region to western Mecklenburg the Low German house was the dominant type of farmhouse. Further east it was found as far as the Danzig Bay, but manor houses (Gutshaus) and farm workers houses were more common. In Schleswig-Holstein it was found mostly south of the Eider river, the old border with Denmark. In northern Sauerland and the Weser Uplands there was less of a sharp boundary and more of a gradual reduction in floor area as the terrain became hillier. In southern Lower Saxony the Hessian square farmstead (Vierkanthof) is found well inside the Low German language area. In east Lower Saxony the Niedersachsenhaus and the square farmstead are interspersed like a mosaic. In Saxony-Anhalt there are none in the Magdeburg Börde and only a few in the Altmark.

This style of house typically appears in the following regions:

|

The Low German house occurs more or less in the areas settled by the Germanic tribes of the Saxons, thus leading its popular name, Low Saxon House, or Niedersachsenhaus, which is based on the Old Saxon cultural region of Low Germany.

Regional features

Within northern Germany the Low German house has numerous regional variations, such as those in the Vierlande and marshes near Hamburg and in the Altes Land near Stade. On these, the gable facing the road were steeply pitched, made of coloured brickwork and is often projecting. In addition the facades were decorated with neoclassical and renaissance designs of the Gründerzeit which lasted to about 1871. Gable design and decorations go back to the area of Hamburg. Another particularly impressive regional variation is the Low German house is found in the Artland near Osnabrück.

See also: Rieck-Huus on Low German Wikipedia

Neighbouring farmhouse types

On the southern boundary of the Low German house region, as well as the multi-sided farmsteads, there is the historical Ernhaus type of farm, also referred to as the Middle German house[1] (mitteldeutsches Haus) or Frankish farmstead[1] (fränkisches Haus). A northern neighbour of the Fachhallenhaus in the immediate vicinity of the North Sea coast was the Gulf house (Gulfhaus) or Frisian farmstead[1] (Ostfriesenhaus) which is found in the marsh regions and, later, also on the geest areas of West Flanders, Frisia as far as Schleswig-Holstein (known there as a Haubarg). It had replaced the Old Frisian farmhouse in the 16th century. Another northern neighbour in the Southern Schleswig area is the Geesthardenhaus, which also occurs in the whole of Jutland and hence is also called the Cimbrian farmhouse.

Construction

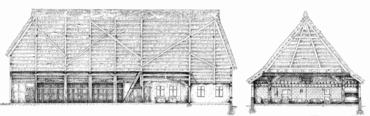

Length: 27 m, Width: 13 m, Height: 12 m

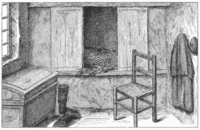

-Side view through the Diele: stalls on the left, living quarters on the right,

-End view through the Flett, the open kitchen

Externally a Low German house is recognisable from the great gateway at the gable end, its timber framework and the vast roof that sweeps down to just above head height. Originally it would have been thatched with reed; the last remaining examples with that type of roof are usually protected as listed buildings today.

The most important feature of the farmhouse, albeit one which is not externally visible, is its internal, wooden, post-and-beam construction which supports the entire building. The frame was originally made of oak, which was very durable, but from the 18th century it was also made from cheaper pinewood. To protect it from damp, the wooden posts rest on a stone foundation about 50 cm high, often made of fieldstone. The non weight-bearing external walls were built as timber frames, the panels of which were originally filled in with willow wickerwork and clay (wattle and daub) and, later, with brick.

In damp moorland and marshy areas the weather-side of the many such buildings was faced with brick. In Westphalia, in addition to the usual timber-framed buildings, there are also hall farmhouses (mostly of the four-post type, see below) whose external walls are made of brick.

The two main forms of construction are the Zweiständerhaus (two-post farmhouse) and the Vierständerhaus (four-post farmhouse). The Dreiständerhaus (three-post farmhouse) is a transitional design.

Design of the I.: two II.: three- and III.: four-post Fachhallenhaus a) tragende Ständer (Hauptständerwerk) b) Ständerwerk Traufe c) Hauptbalkenlage d) Hiehle e) Sparren f) Auflanger g) Aufschiebling |

A sculpture of a Low German Hallhouse framework in Neukirchen-Vluyn, Germany |

Zweiständerhaus

Originally the Low German house took its simplest and basic form, the Zweiständerhaus or two-post farmhouse. This had two rows of uprights on which the ceiling joists rested. The two rows of posts ran the length of the building and created the great central threshing floor or Diele characteristic of this type of farmhouse.[1] On the outside of the rows of uprights, underneath the eaves, low side rooms or bays known as Kübbungen were often built with non load-bearing external walls. These Kübbungen acted as stables or stalls for the cattle[1] and gave this type of house its alternative name of Kübbungshaus. A classic feature of the Zweiständerhaus is that the loft is not supported by the outside walls but only by the two rows of uprights that form part of the hall sides or walls.

Dreiständerhaus

The intermediate variant is the Dreiständerhaus or three-post farmhouse. This is an asymmetric version of the two- and four-post farmhouses, in which the roof ridge is located almost directly over one of the Deele walls. On this side the eaves are like those on the Vierständerhaus, often at the height of the Deele ceiling. On the other side the rafters are arranged like those of a Zweiständerhaus. Often the lower part of the roof is attached on both sides.

Vierständerhaus

The design of the Vierständerhaus or four-post farmhouse is a more comfortable evolutionary development of the Zweiständerhaus built by well-to-do farmers. The building is supported by four rows of uprights arranged longitudinally, of which two form the sides of the Deele and two form the outer walls. So the outsider walls have a load-bearing function. In farmhouses of more affluent farmers there is also a clearer separation between living quarters and animal stalls.

Durchgangshaus

In addition to the normal floor plan there are also farmhouses with a large gateway at both gable ends of the building in order to enable carts to be driven through from end to end. In such a Durchgangshaus or "through house" the layout of the rooms was necessarily different. Even the hearth was not located in the usual place. This variant of the Low German house is often found in Holstein and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, but also occasionally in Westphalia too.

Roof shapes

In Westphalia all these farmhouses have a gable roof. In parts of Lower Saxony and in Holstein there is a mix of farmhouses with gable and hipped-gable roofs, and in Mecklenburg almost all have hipped-gables. A pure hipped roof is rare.

Gable shapes

The original location of the living accommodation in part of the Deele explains the very unusual layout of the Low German house. Whilst other 'all-in-one' farmhouses have their living quarters at the front, the Low German house across most of its native region has its main gateway at the front. The large gateway gable (colloquially: Grotdörgiebel) was very carefully made. The frame and especially the lintel of the Grote Dör (great door) were adorned with inscriptions and decorations. On simple houses the gable above is just filled in with vertical timber laths; on more complicated buildings the timber-framing of the steep gable extends almost to the roof ridge. In the Altes Land projecting gables are preferred. In Schaumburg Land and the area around Hanover the gable is topped by a roof section sloping at about 80°.

The stepped gable on the living room side was only decorated in a few cases, for example, in the Vierlande where it was on the road-facing side.

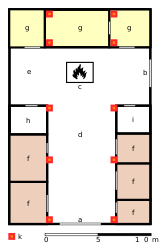

Internal layout

a) Einfahrtstor

b) Seitentor

c) Feuerstelle

d) Diele

e) Flett

f) Stall

g) Stube

h) Futter

i) Gesinde

k) tragender Holzständer

In the 18th century the Low German house was built ever larger, with a length of up to 50 m and width of 15 m. The farmhouse combined all the functions of life on the farm. In this way it was easy for the farmers to manage the whole of his livestock, family and farmhands.

Diele

The largest and most important room in the Low German house was the great central threshing floor, the Diele (Low German: Deele, Del). This was usually entered via the great, rounded door at the gable end, known in Low German as the Grote Dör, Groot Dör or Grotendör ("great door"). The door was also the entrance for harvest wagons leading to the Diele which was like a cavernous hall, hence the alternative name for this type of farmhouse, the Hallenhaus ("hall house"). The Diele was formed by the space between the two rows of supporting uprights. With its tamped clay floor it was the working room of the farmhouse. It was here that the harvest was gathered before being stored in the hayloft above. It also provided protection from the weather for activities, such as the drying of farm implements, the breaking of flax, the spinning of textiles or the threshing of grain. Celebrations, too, were held in the hall and recently deceased members of the family were laid out here. To both sides of the Diele were the half-open stalls or stables (Kübbungen) for cattle or horses, as well as chambers for the maids and farmhands. Poultry would be kept near the entrance way at the edges of the hall. From the outset pigs were banished to separate sheds outside the building due to their smell. Only when living quarters and the Diele area were fully separated from one another could pigs also be encountered in the hall. The Diele opened out into the open eating and kitchen area, the so-called Flett.

Flett

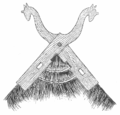

Originally, at the end of the Diele near the back of the farmhouse, was the Flett, an open kitchen and dining area that took up the entire width of the house. The open fireplace, about 1.5 metres across, was located in the middle of the Flett and was ringed with fieldstones. It was not like a hearth in other regions. Many types of cooking were not possible in this environment (*). Pots had to be high enough, in effect cauldrons, and were hung over the fire with pothooks attached to a wooden frame (Rahmen) hanging over the fireplace, often decorated with horses heads. At night an iron grid was pulled over the fire to prevent sparks, a practice known by the English term curfew. Well-to-do families had a candle arch (Schwibbogen) of masonry instead of a wooden frame. Smoke escaped through an opening in the roof on the gable, the Uhlenloch (also Eulenloch, literally: "owl hole"). The open fireplace meant that such buildings were considered as a particular fire risk by early fire insurance firms. The open fire also provided some heat to the stalls and living quarters of the Hallenhaus. In this way, hay stored in the loft could be dried out and protected from vermin by the smoke. When the farmer's family and farm hands gathered for meal times, the best places were between the fireplace and the rooms. Because there was no partition between Diele and loft, winter temperatures in the Flett never rose above 12 °C.

A subsequent improvement was the extraction of smoke through a flue. Still later, a proper hearth would be added with a stone chimney. This made cooking easier and meant that the house was now free of smoke. On the down side, the hearth was no longer really a source of light and there was less energy for heating the house. Later still, one of the larger rooms would be built as a parlour with a separate stove heated from the Diele. When the division of rooms was fundamentally changed in the 19th century, a separate kitchen was established in the living accommodation at the back of the farmhouse. So the farmhouse, which had been divided longitudinally for such a long time, now had its different functions arranged transversely across the building.

(*) Bread was baked outside the farmhouse Hauses in an earth or stone oven. In northwest Germany this only had one chamber. It was first heated, then the embers were raked out and the loaves pushed inside, in order to be baked by the heat stored in the sides of the oven.

Living quarters

Originally there were only open living areas at the back of the farmhouse on both sides of the fireplace. Here there were tables, chairs and wall beds and, of course, open contact with the animals. Not until after the Thirty Years War when the demand for living comfort grew, were separate rooms built at the back of the farmhouse, each the length of a bay (ca. 2.5 m) i.e. the space between the interior posts. This living space was called a Kammerfach from Kammer (room or chamber) and Fach (bay). One subsequent change was the addition of a cellar under the Kammerfach, but it was not very deep. The separate living quarters were raised above the level of the main hall as if on a plinth and in the larger four-post farmhouses (Vierständerhäuser) sometimes formed a sort of gallery.

Decoration

The most eye-catching decoration of the otherwise drab Fachhallenhaus is found on the point of the gables and consists of carved wooden boards in the shape of (stylised) horses' heads. The boards do serve a constructional purpose in that they protect the edges of the roof from the wind. The horses' heads are attributed to the symbol of the Saxons, the Saxon Steed. Its distribution as decoration on roof ridges is also reflected in the coats of arms of several north Germany towns and villages. In some regions, e. g. in the Hanoverian Wendland, the gable points often have an artistically turned post instead, the so-called Wendenknüppel.

Drawing of a gable decoration 1901

Drawing of a gable decoration 1901 Gable decoration in 2006

Gable decoration in 2006 Horses's heads on the coat of arms of Buchholz in der Nordheide

Horses's heads on the coat of arms of Buchholz in der Nordheide Coat of arms from Spornitz in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

Coat of arms from Spornitz in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern In Ravensberg Land the gables are usually decorated with a post known as a Geckpfahl.

In Ravensberg Land the gables are usually decorated with a post known as a Geckpfahl.

Other decorations or mottos are usually found as inscriptions over the entranceway. The lintel gives the name of the builder, the year the house was built and often another saying. Occasionally modest decorations are found on the timber framed, front gable. They are designed into the brickwork of the panels and portray, for example, windmills, trees or geometric figures

Decline

By the end of the 19th century this type of farmhouse was outmoded. What was once its greatest advantage – having everything under a single roof – now led to its decline. Rising standards of living meant that the smells, breath and manure from the animals was increasingly viewed as unhygienic. In addition the living quarters became too small for the needs of the occupants. Higher harvest returns and the use of farm machinery in the Gründerzeit led to the construction of modern buildings. The old stalls under the eaves were considered too small for today's cattle. Since the middle of the 19th century fewer and fewer of these farmhouses were built and some of the existing ones were converted to adapt to new circumstances. Often the old buildings were torn down in order to create space for new ones. In the original region where once the Low German house was common, it was increasingly replaced by the Ernhaus whose main characteristic was a separation of living quarters from the livestock sheds.

Present-day situation

The Low German house is still found in great numbers in the countryside. Most of the existing buildings have, however, changed over the course of the centuries as modifications have been carried out. Those farmhouses that have survived in their original form are mainly to be found in open-air museums like the Detmold_Open-air_Museum (Westfälisches Freilichtmuseum Detmold) in Detmold and the Cloppenburg Museum Village (Museumsdorf Cloppenburg). The latter has set itself the task of uncovering rural historic buildings in Lower Saxony and documenting the most important examples accurately. For the state of Schleswig-Holstein the Schleswig-Holstein Open Air Museum (Schleswig-Holsteinisches Freilichtmuseum) in Kiel-Molfsee is the most important one with its large collection of Fachhallenhäuser and the like. Several of these buildings may also be found at the Kiekeberg Open Air Museum (Freilichtmuseum am Kiekeberg) and the Volksdorf Museum Village (Museumsdorf Volksdorf) in Hamburg; Examples from the eastern part of the Hallenhaus region are displayed in the Schwerin-Mueß Open Air Museum (Freilichtmuseum Schwerin-Mueß).

At the end of the 20th century old timber-framed houses, including the Low German house, were seen as increasingly valuable. As part of a renewed interest in the past, many buildings were restored and returned to residential use. In various towns and villages, such as Wolfsburg-Kästorf, Isernhagen and Dinklage, new timber-framed homes were built during the 1990s, whose architecture is reminiscent of the historic Hallenhäuser. The oldest still in use farm in North and Western Europe is the Armenhoef in the south of the Netherlands.

Dat ole Huus in Wilsede dating to about 1540

Dat ole Huus in Wilsede dating to about 1540 Fachhallenhaus in Isernhagen, today the North Hanoverian Farmhouse Museum

Fachhallenhaus in Isernhagen, today the North Hanoverian Farmhouse Museum Modern home built as a Fachhallenhaus replica

Modern home built as a Fachhallenhaus replica Hof der Heidmark in Bad Fallingbostel dating to 1642

Hof der Heidmark in Bad Fallingbostel dating to 1642- Farmhouse in Admannshagen-Bargeshagen

- Unrestored farm-

house in Wiendorf - Farmhouse in Pepelow, Am Salzhaff

See also

- Hösseringen Museum Village, particularly the museum house Commons:Category:Kötnerhaus von1596

- Vernacular architecture

References

- Dickinson, Robert E. (1964). Germany: A regional and economic geography (2nd ed.). London: Methuen. pp. 151–153.

- Elkins, T.H. (1972). Germany (3rd ed.). London: Chatto & Windus, 1972, p. 266. ASIN B0011Z9KJA

- http://www.gemeentebest.nl/sport-cultuur-en-recreatie/monumenten/68/de-armenhoef-oirschotseweg-117.html

Sources

- Richard Andree: Braunschweiger Volkskunde. Braunschweig 1901.

- Karl Baumgarten: Das deutsche Bauernhaus, eine Einführung in seine Geschichte vom 9. bis zum 19. Jh. Berlin 1980, ISBN 3-529-02652-2

- Karl Baumgarten: Das Bauernhaus in Mecklenburg. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1965, 1970 (Neuaufl. u. d. Titel „Hallenhäuser in Mecklenburg“.)

- Karl Baumgarten: Landschaft und Bauernhaus in Mecklenburg. Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-345-00051-2

- Konrad Bedal: Ländliche Ständerbauten des 15. bis 17. Jahrhunderts in Holstein und im südlichen Schleswig. Wachholtz, Neumünster 1977, ISBN 3-529-02450-3

- Frank Braun, Manfred Schenkenberg: Ländliche Fachwerkbauten des 17. bis 19. Jahrhunderts im Kreis Herzogtum Lauenburg. Wachholtz, Neumünster 2001, ISBN 3-529-02597-6

- Carl Ingwer Johannsen: Das Niederdeutsche Hallenhaus und seine Nebengebäude im Landkreis Lüchow-Dannenberg. Dissertation. Braunschweig 1973.

- Horst Lehrke: Das niedersächsische Bauernhaus in Waldeck (Beiträge zur Volkskunde Hessens, Band 8). 2. Auflage, Marburg 1967

- Werner Lindner: Das niedersächsische Bauernhaus. Hannover 1912.

- Willi Pessler: Das altsächsische Bauernhaus. Braunschweig 1906.

- Josef Schepers: Haus und Hof westfälischer Bauern. 7., neubearb. Auflage, Münster 1994.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Low German houses. |

- Farmhouses in Lower Saxony (main focus on the Fachhallenhaus with distribution map, photographs and sketches - German)

- Description of the building by the Cloppenburg Museumsdorf - German

- Floor plan at Fachwerk-Lehmbau.de - German

- Timber framed and Fachhallenhaus buildings in Altes Land (Stade) - German

- Bielefeld Farmhouse Museum - German

- A Low German house in the Weser-Ems region - German