Fabio Campana

Fabio Campana (14 January 1819 – 2 February 1882) was an Italian composer, opera director, conductor, and singing teacher who composed eight operas which premiered between 1838 and 1869.[1] He was born in Livorno, the city where his first two operas premiered, but in the early 1850s he settled in London. There he opened a famous singing school, conducted concerts, and continued his reputation as a prolific and popular composer of art songs and concert arias.[2] His last opera, Esmeralda, premiered in Saint Petersburg in 1869, followed by London performances in 1870 with Adelina Patti in the title role. Campana died in London at the age of 63. Although his operas are no longer performed, his art songs can be heard on several modern recordings.

Life and career

Campana was born in Livorno and initially studied music there with Bernardo Nucci before going on to further studies at the Naples Conservatory and finally at the Accademia Filarmonica di Bologna. His first opera Caterina di Guisa, set to a libretto by Felice Romani, premiered while he was still a student.[3] It was first performed on 14 August 1838 at the Teatro degli Avvalorati in Livorno, with Verdi's future wife Giuseppina Strepponi in the title role.[4] The opera was warmly received as was his next opera Giulio d'Este which premiered at the same theatre in 1841. Campana also directed several operas at the theatre, including Mercadante's Il giuramento (1839), Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor (1840), Meyerbeer's Il crociato in Egitto (1840), and Bellini's Il pirata (1840).[4]

In addition to conducting the premiere of his own opera, Vannina d'Ornano at the Teatro della Pergola in Florence (1842), he conducted a series of concerts in Rome, including a performance of Rossini's Stabat Mater. His last opera to be premiered in Italy was Mazeppa, with a libretto based on Byron's narrative poem, Mazeppa. It was first performed at the Teatro Comunale di Bologna on 6 November 1850 with the tenor Settimio Malvezzi in the title role.[5]

In 1850 Campana had gone to Paris, armed with a letter of recommendation from Rossini to seek a position at the Théâtre des Italiens which at that time was run by Benjamin Lumley.[1] He was unsuccessful, however, and returned to Italy. Then on the suggestion of Lord Ward, a principal benefactor of Her Majesty's Theatre, he went to London where he was to live for the rest of his life. There he opened a famous singing school, conducted concerts, and continued his reputation as a prolific and popular composer of art songs.[2] The first of his "Grand Matinee Musicale" concerts took place in 1854 under the patronage of Lord Ward, and featured his latest compositions. The 1860s saw the premieres of his last two operas. Almina premiered in London at Her Majesty's Theatre on 26 April 1860 conducted by Luigi Arditi with Marietta Piccolomini in the title role.[6] The critical reaction was tepid. The Musical World criticised its lack of "dramatic fire", but also went on to note that the audience did not appear to share that view:

Taking applause as a criterion, the success of Almina was triumphant. After the first act, the principal singers were recalled, and then Signor Campana was compelled to appear, when he was not merely received with tumultuous acclamations, but fêted with bouquets and laurel-wreaths. At the fall of the curtain, too, he was summoned to the foot-lights twice, when the demonstrations were renewed, and no doubt the composer left the theatre perfectly satisfied that his opera had achieved a great and legitimate triumph. First nights, however, are not always precedents—the Barbiere of Rossini to witness.[7]

Campana's final opera Esmeralda, based on Victor Hugo's The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, premiered in Russia at the Saint Petersburg Imperial Italian Opera on 20 December 1869. The title role had been written expressly for Adelina Patti, but she could not make the Saint Petersburg premiere and the role was sung by Carolina Volpi instead. In June of the following year, it was mounted in London at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden this time with Adelina Patti as Esmeralda. The French journal Le Ménestrel reporting on the Saint Petersburg premiere praised the opera for its beautiful melodies and orchestration. The English critics' reaction to the London premiere was scathing. Henry Lunn, writing in The Musical Times, called it "a feeble work" with "commonplace" music, rescued only by the singing of Patti.[8] The critic for The Saturday Review pronounced it "irredeemably bad".[9] However, in his review of the London performance for Le Ménestrel, Joseph Tagliafico (writing under his pseudonym "De Retz") took exception to the vehemence of the English critics' reaction finding it inexplicable. He concluded his review:

They say of Campana's opera that it is [simply] a new Album of Songs by the composer. Bah! Could not one also say that Donizetti's La favorite is a romanza in five acts? The future will decide who was right and who was wrong.[10]

Esmeralda ran for a couple of seasons in London and was also performed in Hamburg (again with Patti in the title role) and in Trieste but then dropped from the repertoire. Fabio Campana died in London on 2 February 1882 at the age of 63. His operas are no longer performed, but his art songs can be heard on several modern recordings, including Opera Rara's Il Salotto series, and Joan Sutherland's 1978 LP set Serate Musicali (re-released on CD by Decca in 2006). A portrait of Campana by Giovanni Fattori hangs in the Museo Civico Giovanni Fattori in Livorno.[11]

Operas

- Caterina di Guisa (tragedy in 3 acts, libretto by Felice Romani; premiered Livorno, Teatro degli Avvalorati, 14 August 1838)[12]

- Giulio d'Este (tragedy in 3 acts, libretto by Carlo Alberto Monteverde; premiered Livorno, Teatro degli Avvalorati, 28 August 1841)

- Vannina d'Ornano (tragedy in 3 acts, libretto by Francesco Guidi; premiered Florence, Teatro della Pergola, 1 June 1842)

- Luisa di Francia (melodrama in 4 parts, libretto by Francesco Guidi; premiered Rome, Teatro Argentina, 29 April 1844)

- La Duchessa de La Vallière (melodrama in 4 parts, libretto by Francesco Guidi; Livorno, Teatro Rossini, summer 1849)

- Mazeppa (lyric drama in 4 parts, libretto by Achille de Lauzières-Thémines; premiered Bologna, Teatro Comunale, 6 November 1850)

- Almina (lyric drama in 3 acts, libretto by Achille de Lauzières-Thémines, premiered London, Her Majesty's Theatre, 26 April 1860)

- Esmeralda (lyric drama in 4 acts, libretto by Giorgio Tommaso Cimino; premiered Saint Petersburg, Imperial Italian Opera, 20 December 1869)

Songs

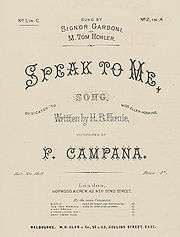

Campana composed at least two patriotic songs during the 1848–1849 Italian revolutions. One was set to Arcangelo Berettoni's poem "La costituente italiana" (The Italian Constituent).[13] The other, "Inno nazionale" (National Hymn) set to a text by Franco Carrai, became the most frequently sung song in Livorno at the time.[14] He also composed a chorus to accompany a dramatic allegory performed at the Teatro degli Avvalorati in 1847 to celebrate Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany granting Livorno its own Civil Guard.[15] Between 1846 and 1854, Francesco Lucca, the firm which had commissioned Verdi's early opera Il corsaro,[16] published seven collections of Campana's songs. Ricordi was to publish another nineteen between 1851 and 1873. The Ricordi collections were variously entitled Souvenirs, Pensieri, Echi, Sospiri, or Ricordi (Souvenirs, Thoughts, Echoes, Sighs, Memories), with each one devoted to a different place which had a personal significance in Campana's life, including Naples, Venice, Rome, Paris, Bagni di Lucca, and Lake Como.[2] The majority of Campana's songs were set to Italian texts, some written by the composer himself such as "Quando da te lontano!" (When I Am Far From You!). However, he also set texts by English writers which became popular both as concert pieces and as parlor songs. His most well-known collaborators in this genre were Henry Brougham Farnie (e.g. "Speak to Me" and "The Scout: A Trooper's Ditty") and Henry Hersee (e.g. "A Free Lance Am I: Or the Soldier of Fortune" and "The Little Gipsy").[17] Another popular concert piece in England was Campana's "Voga, voga, O marinaro" (Row, Row, O Sailor), a barcarole for three female voices. It was later mentioned in Eleanor Farjeon's 1941 novel, Miss Gransby's Secret, a satire on the sensibilities of the Victorian era.[18]

- Recorded songs

- "L'ultima speme" (The Last Hope) – Joan Sutherland (soprano), Richard Bonynge (piano) on Serate Musicali (Decca)

- "Una sera d'amore" (An Evening of Love) – Jennifer Larmore (mezzo-soprano), Patrizia Biccire (soprano), Antoine Palloc (piano), on Il Salotto Vol 8: Notturno (Opera Rara)

- "Ora divina" (Divine Hour) – Paul Austin Kelly (tenor), Diana Montague (mezzo-soprano), David Harper (piano) on Il Salotto Vol 9: Ora Divina (Opera Rara)

- "Près de la mer" (By the Sea) – Diana Montague (mezzo-soprano), David Harper (piano) on Il Salotto Vol 11: Serenata (Opera Rara)

Notes and references

- Ambìveri (1998) p. 32

- Sanvitale (2002) p. 153

- Forbes

- Casaglia

- Born in Florence, Settimio Malvezzi (1817–1887) created several leading tenor roles in 19th operas, most notably Rodolfo in Verdi's Luisa Miller.

- Born in Siena, Marietta Piccolomini (1834–1899) was a leading soprano of her day and later a well-known voice teacher.

- The Musical World (28 April 1860) p. 273. The critic here is referring to Rossini's The Barber of Seville which had a disastrous opening night.

- Lunn (1 September 1871) p. 199

- The Saturday Review, 18 June 1870, reprinted in Dwight's Journal of Music (30 July 1870) p. 282

- De Retz (26 June 1870) p. 237. Original French: "On a dit de l'opéra de Campana que c'était un nouvel 'Album de mélodies' de l'auteur. Bah ! N'a-t-on pas dit ici que la 'Favorite' de Donizetti était une romance en cinq actes? L'avenir prouvera qui a tort ou raison."

- Durbè (1980) p. 147

- Librettist and premiere information in this section is based on Ambìveri (1998) p. 33 and Casaglia (2005)

- Archives of the Fondazione Roselli, which also has a scan of the lyrics

- Durbè (1980) p. 149

- Catalogue of the Biblioteca Labronica Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine. The work was called La gioia livornese per la concessa Guardia Civica (Livornese Joy at the Concession of the Civil Guard).

- Bianconi and Pestelli (1998) p. 159

- Henry Hersee (1820–96) was a music critic, librettist, and translator of many operas into English.

- Farjeon (1941) pp. 61 and 154. For a review of the novel, see "Victorian Satire", The Argus, 1 March 1941, p. 6.

Sources

- Ambìveri, Corrado, "Fabio Campana", Operisti minori dell'800 italiano, Gremese Editore, 1998, pp. 32–33. ISBN 88-7742-263-7 (in Italian)

- Bianconi, Lorenzo and Pestelli, Giorgio, Opera Production and its Resources (translated by Lydia G. Cochrane), University of Chicago Press, 1998. ISBN 0-226-04590-0

- Casaglia, Gherardo (2005)."Fabio Campana". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- De Retz, "Saison de Londres", Le Ménestrel, 26 June 1870 pp. 236–237 (in French)

- Durbè, Vera (ed.), La Giovinezza di Fattori: Catalogo della mostra al Cisternino del Poccianti: Livorno, ottobre–dicembre 1980, De Luca, 1980 (in Italian)

- Dwight's Journal of Music, "The Italian Operas in London—Covent Garden", Vol 30, No. 10, 30 July 1870, pp. 282–283

- Farjeon, Eleanor, Miss Gransby's Secret, Simon and Schuster, 1941

- Forbes, Elizabeth, "Campana, Fabio", Grove Music Online, Accessed via subscription 25 September 2010

- Lunn, Henry C. "The London Musical Season", The Musical Times, Vol. 15, No. 343, 1 September 1871, pp. 199–202 .

- Sanvitale, Francesco, La romanza italiana da salotto, EDT srl, 2002. ISBN 88-7063-615-1 (in Italian)

- The Musical World, "Her Majesty's Theatre", 28 April 1860, p. 273

External links

- Free scores by Fabio Campana at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP), songs "La Malinconia" and "Amo"

- Complete score of Campana's Mazeppa at the Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek

- Catalogue of Fabio Campana's scores held in the libraries of Tuscany (in Italian)