Experimental three-phase railcar

The Three-phase railcar (Ger: Drehstrom-Triebwagen) was an experimental railcar built in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century to assess the possibilities in using electric motive power for rail transport.

Background

The 19th century saw the invention of the modern railway and their rapid expansion into national networks in Europe and worldwide. During this period motive power was confined to steam locomotives, some of which by mid-century were capable of top speeds of 80 miles per hour (130 km/h), with average express journey speeds of 50–60 mph (80–97 km/h).

The 1880s saw the development of electric power and its application to rail transport. Electric power offered several advantages over steam; it is more efficient, allowing more rapid acceleration, and a higher power output when necessary. Its disadvantage is the high initial cost of the infrastructure involved, such as the power production and distribution system needed. 1879 saw the demonstration of an experimental system by Werner von Siemens in Berlin, which was followed by an electric tramway at Lichterfelde, in 1881, and heavy rail applications in 1890 (the City and South London Railway) and 1895 (the Baltimore Belt Line).

In 1899 a consortium of ten of the largest and wealthiest companies in Germany joined together to form the "Research Association for High-speed Electric Railways"(de) (Studiengesellschaft für elektrische Schnellbahnen, or St.E.S.) to examine the possibilities of high-speed electric rail travel.

Research Association for High-speed Electric Railways

The St.E.S consortium, which included Siemens & Halske, the engineering company AEG, and the Deutsche Bank, was founded on 10 October 1899 and given leave to electrify a length of the Royal Prussian Military Railway between Marienfelde, near Berlin, and Zossen, a distance of 23 kilometres (14 mi). The line was electrified with three-phase power at 10 kV/50 Hz, using three overhead lines on poles that were about 5 to 7 metres (16 to 23 ft) high located at the side of the track. This work was completed by the spring of 1901.

The three-phase railcar

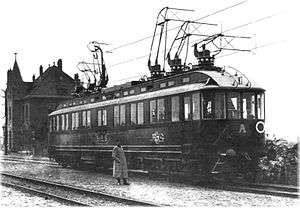

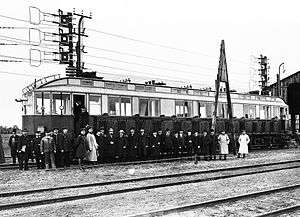

The society commissioned two railcars for testing. These were built by Van der Zypen & Charlier, a Cologne rolling-stock manufacturer and consortium member, with Siemens and AEG supplying the electrical equipment. The cars were of standard size, with a capacity for 50 passengers, mounted on two six-wheel bogies, the outer axle being motorized. The power was drawn down from the three power cables running along the side of the track by three vertical catenaries, mounted on two towers fore and aft on the roof of the carriage. The electrical system was rated at 6–14 kV, operating at 25–50 Hz, giving a power equivalent of 1,475 hp (1,100 kW).[1]

The summer of 1901 saw a series of test runs, culminating in record-breaking speeds of 160 kilometres per hour (99 mph). These tests revealed weaknesses in the trackbed, which had to be re-laid. Following this, in the autumn of 1903, a series of high-speed runs were achieved; of 206 kilometres per hour (128 mph), by the Siemens railcar, on 6 October, and 210 kilometres per hour (130 mph), by the AEG railcar, three weeks later, on 28 October 1903. This set a land speed record for rail vehicles (electric) which stood for the next 51 years.[2]

The tests had shown what was possible with electric motive power, but the three-phase system was too complex, and the cost of installation too prohibitive, for general use across the rail network. With this the St.E.S was wound up and the infrastructure dismantled. However advances in technology, particularly in semiconductors, are believed to offer new possibilities with the three-phase system.[3]

Notes

- Dorling Kindersley 2014, p. 124.

- Zossen.de Archived July 15, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "Transporte Brasileiro - Mobility". Siemens. Archived from the original on 2011-10-02. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

References

- The Train Book: The Definitive Visual History. Dorling Kindersley. 2014. ISBN 9780241187890.