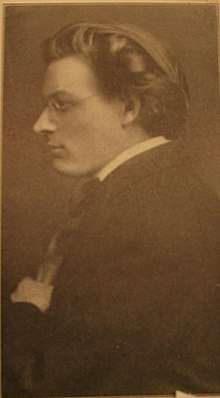

Eugen Haile

Eugen Haile (February 21, 1873 – August 14, 1933) was a German-American composer, singer, and accompanist, primarily known for his songs.[1] In his lifetime, it was claimed that he was one of the "truly inspired melodists, a lineal descendent of the great lyricists, Schubert, Schumann, Franz and Brahms."[2]

Biography

Early life

Haile was born in Ulm,[2] Germany, a town described by a columnist who interviewed Haile as "the old Suabian town of Meistersinger traditions",[3] "on the fringe of the Black Forest".[2] His father was a local butcher.[4]

During his childhood Haile liked the zither, and also played the flute, which he learned from "an old town musician ... The boy preferred to play by ear and in the open; or to improvise an obbligato to the deep bass of an old shoemaker friend whose singing of chorals he enjoyed." He loved "emotional spontenaity" and folksong, and had a "preference for simple sentiments simply and sincerely expressed".[3]

In 1887, at age 14,[2] he went to study at the Stuttgart Conservatory,[1] where he learned violin, piano, and composition.[3] Haile spent seven years there, until 1894.[2]

Career and marriage

During the next few years, Haile composed songs that he said were popular with audiences, but not with the musical authorities.[2] Also, while in Stuttgart, Haile began work on an opera called Harald der Geiger. The librettist was a friend, who entered the priesthood and moved to America before the text was finished. Haile eventually followed him in 1903,[1] settling in Scranton, Pennsylvania for a few years. While there, Haile conducted male singing societies,[2] sent for his fiancee, Elise,[5] and got married. His wife was a contralto,[5] who was also from Germany, and had worked in Stuttgart.[6]

Around 1905, Haile began work on a second opera, called Viola d'Amore.[2] Its libretto was written by Baron Hans von Wolzogen (a "litterateur and musical critic," and a friend of Wagner).[6]

In the first decade of the 20th century, the Hailes moved to New York City, living (at least at one time) on West 145th St.[7] They became active in the musical life of the city. In November, 1907, the singer Theodore Van Yorx gave a recital of Haile's songs at Mendelssohn Hall in New York City, accompanied by the composer at the piano. The program consisted of readings by Van Yorx from Haile's autobiography, interspersed with songs.[8]

Van Yorx frequently performed Haile's songs. The reviewer of the November 1907 concert said, "Van Yorx has sung these songs in over a dozen cities in the country".[9] Singer Ludwig Hess also performed Haile's songs in the original German, in several recitals, singing "Teufelslied," "Der fahrende Musikant," and "Es vegnet".[6]

Haile was a baritone and frequent accompanist.[5] Together with his wife, he also presented several concerts of his own songs in New York City.[1]

In 1911, Haile was getting nearer to completing his opera Viola d'Amore. Some time in early to mid 1911, Mrs. Haile went back to visit Germany.[6] The opera received private hearings in "German musical circles;" and Max Schillings, the Music Director of the Royal Opera House at Stuttgart, promised to produce it when it was finished.[6][10] Many of Haile's songs were published in Germany shortly thereafter by Friedrich Hofmeister Musikverlag (see list of compositions, below).

The Hailes spent mid to late 1911 at "Blythewood, Barrytown," New York.[6] Haile and his wife gave two recitals of his songs together on December 8 and 10, 1911, at Rumford Hall, New York City.[5]

Haile and his wife gave two more New York City recitals of his songs together on January 9 and January 29, 1912, also at Rumford Hall.[6] Haile played all accompaniments.[11] In the January 9th recital, Haile seems to have introduced a new, more declamatory and more modern compositional style. A reviewer said, "The translation of the sentiment of the poems into tonal utterances is his aim ... To the lover of melody, these songs offer little".[12] (See "Compositional style and compositions" section for longer quote.) In the recital on January 29, they performed his latest more conservatively styled songs; the audience's favorite was "König Elf". A reviewer from Musical America said that it "has great emotional power, especially the final picture of tragedy." Another song, "Verrat", was described as having a "quaint melody".[13]

Illness and later career

Some time in 1912 or early 1913, Haile became almost entirely paralyzed, and was forced to stop all composing.[3][4] On May 2, 1913, singer Ludwig Hess gave a benefit concert for Haile, because he was "grevously ill." Hess sang a group of six songs by Haile, and various works by other composers. Other performers included Sara Gurowitsch (cello), Cécile Behrens (piano), and the Hess Soloists Ensemble.[14] A Eugen Haile Society was formed in New York in 1914 to organize further performances of his music,[1] to work for the publication of Haile's recent compositions, and to raise funds to support him and his family.[3]

In 1915, a columnist wrote that Haile was paralyzed, and could not compose or teach, but could talk. He gave an interview to Amelia von Ende of Musical America. During their discussion, he said that contemporary music was too intellectual.[15]

In 1916, while still unable to walk, Haile composed a musical setting to a play.[10] He "dictated" the orchestral score in six months.[2] The play was written by J. and L. du Rocher MacPherson, and directed by Arthur Hopkins. Entitled The Happy Ending, it was produced in New York City, at the Schubert Theatre.[10][16] The show premiered on August 21, 1916. In the score, Haile combined spoken words with pitch inflections, in the manner of Sprechstimme.[1][4] Happy Ending ran for about a month.[16] An interviewer said: "This score might have been one of mere incidental music, but the composer saw in the imaginative and poetic quality of the text ... the music drama of his dreams".[4] Haile composed it in his more declamatory, modern style, making free use of leitmotifs.[10]

The actors in the play presented Haile with a testimonial, inscribed on parchment, expressing their admiration for his work.[17]

There does not seem to be any evidence that Haile ever finished his opera Viola d'Amore.

On May 8, 1917, another benefit concert was given for Haile. There were three singers and accompanists performing, some from the Metropolitan Opera:[2] Marie Mattfeld and Mattfeld, Margarete Ober and Arthur Arndt, and Carl Braun and Richard Epstein. Many of Haile's songs were performed, including "Fitzebutze" (sung by Ms. Mattfeld), "Verlungene Weise" (sung by Braun), "Eidechs" (a comical song, also sung by Braun), and "Herbst." The concert also featured some works for cello and piano, played by Leo Schultz and Epstein. Epstein also played some solo piano works.[18]

After the benefit, the National Society of Music published an article about Haile in their bulletin, that said, "Whatever may be Eugen Haile's ultimate place in music, one thing is certain: that he will always be recognized as one of the truly inspired melodists, a lineal descendent of the great lyricists, Schubert, Schumann, Franz and Brahms".[2] Also shortly after the benefit, Haile gave another interview. The interviewer states that Haile was still bedridden, but could compose. The author describes Haile as a representative of the tradition of German lieder.[2]

In 1924, H. W. Gray Co. published a children's book by Haile, entitled A Riddle Book with Melodies.[19]

Haile lived to see an opera of his produced, Harold's Dream, performed in Woodstock, New York on June 30, 1933.[1] It was performed on June 30, 1933, in the Romantic-style garden of the estate of and Mrs. Antonio Knauth of Kingston, New York.[20] The opera's plot is a fantasy, and was called "the Prelude to the romantic opera Harald",[20] possibly indicating that it was related to his first, unfinished opera, Harald der Geiger.

The libretto was by Otto Lauxman.[20] The cast included Winifred Haile, dramatic soprano,[20] an orchestra, and a chorus.[20] The Music Director was J. Peter Knauth; the Choral director was Harry Elmendorf; the Concertmaster was Gerald Kunz; Otto Riccobono and Agnes Schleicher were the Choreographers and Dance Directors; the scenery was by Konrad Cramer; and Louis Staketee and Robert Briggs were the Lighting Directors.[20]

Haile died in Woodstock, New York.[1][21]

Compositional style and compositions

Compositional style

A reviewer of the November 1907 concert of Haile's works described his compositional style thus: "That Haile has real poetic genius and a facility in writing tender, dainty and delightful little songs, full of melody and feeling, there is no doubt."[8]

In 1912, Haile seems to have begun to present works in a more modern style. A reviewer from the Musical Courier said of Haile's January 9, 1912 concert:

[The songs on the program] disclosed a talent on the part of the composer of a serious character, well developed and well defined, with a preponderance of the solemn and grave, although in certain of the songs there is much delicacy and considerable sentiment. Haile evidently is a student of basic principles. He never descends to the commonplace or writes merely for the sake of effect. The translation of the sentiment of the poems into tonal utterance is his aim, and his music not only substantiates this deduction, but his interpretations are also corroborative of it. To the unmusical, to the lover of melody, these songs offer little, but to him who possesses sufficient perspicacity to observe substratum things, there is a wealth of beauty and art in these songs which can hardly fail of satisfaction or enjoyment.[12]

Haile's 1916 musical setting of the play The Happy Ending followed this more contemporary strain in his writing, combining spoken words with pitch inflections, in the manner of Sprechstimme.[1][4] A reviewer described Haile's setting of The Happy Ending, saying:

Mr Haile has taken hold of the text of The Happy Ending and worked with it quite as seriously as though it were the libretto for an opera. He has by no means limited himself to "incidental music" - to entr'actes, intermezzi, songs and the like. Finding that much of the action and dialog was of a poetic nature which demanded music, he composed a score which is intimately interwoven with the play. He has used leitmotifs freely, and has developed them in transformation and combination according to the demands of the play. He regards his score as a form of music-drama with spoken text".[10]

Another interviewer said that The Happy Ending as "not a success as a play; but the music, a wonderfully limpid undercurrent of sound that accompanied the words, a continuous surge of beautiful, inspired melody, brought tears to the eyes of critics, and the audience turned to the box where the invalid composer lay and shouted its satisfaction, repeating the demonstration on the street when he was being carried to his cab".[2]

Haile did not leave the conservative style totally behind, however. A reviewer from The New York Times said, in an article about Haile's January 29, 1912 recital:

Mr Haile's songs are marked by simplicity and directness, without affectation of "modern" feeling, where such an impulse did not come from the composer. He is evidently much influenced by the element of German folksong, and several of his compositions are happy in a deliberate and intentional embodiment of that spirit ... Haile also has a fondness for songs with descriptive or characteristic accompaniments [including the songs "Teufelslied," "Werkeluhr", and ... the ballad "König Elf, [which is] "... a rather elaborate attempt at the kind exemplified by Loewe's ballads ... Haile's talent is modest and unpretentious, but it has individuality and a personal note that are valuable and none too common qualities in music made in the present day".[11]

Another reviewer of Haile's January 29 recital confirmed the conservatism of this program's songs. The selections were "free from affectation and the modern tendency to launch forth into dissonances and individual mannerisms ... At times there is an indication of the influence of the great composers, especially Chopin and Wagner".[22]

In an interview in 1915, Haile said that contemporary music was too intellectual. He described his own philosophy of music by quoting the idealistic French author Romain Rolland and holistic music educator Francois Dalcroze (sic, Émile Jaques-Dalcroze?), sharing their philosophies, adapted to his own field of music.[3] In this interview, Haile also compared his musical gift to the poetic talent of Verlaine (who wrote mostly in small forms[23]), saying, "In his very limitation, he proves himself a master".[3]

Compositions

Haile is best known for the approximately 200 songs that he wrote to German texts,[1] about 65 of which were published, mostly in Germany, (copies are available in the Eugen Haile Papers collection at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts), and some also published in America.[21] His other vocal works include several duets and works for male quartet (also in collection), three operas, Harald der Geiger[4] (unfinished),[4] Viola d'Amore[6] (unfinished),[4] and Harold's Dream[1] (premiered June 30, 1933),[20] and a musical setting for a play called The Happy Ending, produced in New York City in 1916.[10]

Haile also wrote two cantatas, one called Christabend, for mixed chorus, soprano and baritone soli, and piano, published privately in Ulm, c.1900,[24] and a good-sized manuscript of a cantata entitled Peace, both works available in his collection at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.[25]

His instrumental works include a sonata for violin and piano and several other chamber pieces, also available in Haile's papers at the NYPL.

In 1924, H. W. Gray Co. published a book of children's songs by Haile, entitled A Riddle Book with Melodies.[19]

Selected works

(Note: all works available from the Eugen Haile Papers collection, at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.)

Published solo songs

- "Abendlied" (Evening song; poem by Martin Greif) Op.4, No.2. Stuttgart: Verlag der Ebner'schen Hof-Musikalienhandlung, n.d.

- "Am Brunnen" (By the brookside; poem by Martin Greif) Leipzig: Verlag von Friedrich Hofmeister, c.1914

- "Die Blumen stehen am Bächlein" (poem by Theobald Kerner) Leipzig: Verlag von Friedrich Hofmeister, c.1914

- "Blümlein zart vom Sturm verheert". Stuttgart: Verlag der Ebner'schen Hof-Musikalienhandlung, [ca.1910][26]

- "Der Egoist" (poem by Theodor Kirchner) New York: Luckhardt & Belder, c1906,[26] Leipzig: Verlag von Friedrich Hofmeister, c1906, 1911

- "Der Eidechs" (The Lizard; poem by Heinrich von Reder; comical[18]) Leipzig: Verlag von Friedrich Hofmeister, c1915

- "Es ist ein dunkles Auge" (poem by Gustav Kastropp; for medium voice; written at age 15, his earliest song published), Op.7, No.1. Leipzig: Verlag von Friedrich Hofmeister, n.d.

- "Es regnet" (poem by A. Petöfi) Leipzig: Verlag von Friedrich Hofmeister, c1911

- "Der fahrende Musikant" (poem by S. Pfau) Leipzig: Verlag von Friedrich Hofmeister, c1911

- "Ein Freund ging nach Amerika" (My friend's gone to America; poem by Peter Rosegger; in German and English) Leipzig: Verlag von Friedrich Hofmeister, c1914

- "Frühlings Nahen" (poem by E. Degen; for soprano) New York: Luckhardt & Belder, c1905;[26] Leipzig: Verlag von Friedrich Hofmeister, n.d.

- "Frühlings Narretei" (Spring's foolery; text by Carl Busse, shows "elfish merriment"[3]) New York: Luckhardt & Belder, c1906[26]

- "Gleich und Gleich" (For each other; poem by Goethe; "tender and sincerely expressive"[11]) Leipzig: Verlag von Friedrich Hofmeister, c1906

- "Herbst" (Autumn), Op.15, No.3 Leipzig: Verlag von Friedrich Hofmeister, c1905; New York, Lukhardt & Belder, c1905[26]

- "Im Zitternden Mondlicht" (In the moonlight; "dreamy...with its haunting melody"[11]) New York: Lugkhardt & Belder, c1906, 1908[26]

- "Kein Echo" (No echo; set"to words by Dingelstedt, is a superb example [of] reflecting a sympathetic poem's spirit with that truthfulness which make for genuine unity of words and music"[3]) Stuttgart: Verlag der Ebner'schen Hof-Musikalienhandlung, n.d.[26]

- "Meine Seele" (My soul) Publisher's proof, n.d.

- "Soldaten kommen" (Soldiers are coming)Stuttgart: Verlag der Ebner'schen Hof-Musikalienhandlung, n.d.[26]

- "Suomis Sang Horch wie hehr Akorde schallen" (Suomi's Song), Op.10, No.1. (for baritone; text after a Swedish poem; called "a glorification of the Finnish language...[it] has a striking and original quality, with a strong undercurrent of sadness"[11]) Stuttgart: Verlag der Ebner'schen Hof-Musikalienhandlung, n.d.[26]

- "Der Todesengel singt" (The Angel of Death sings) Stuttgart: Verlag der Ebner'schen Hof-Musikalienhandlung, n.d.

- "Über den Bergen" (Over the hills; text by Carl Busse; shows a "dirgeful mournfulness";[3] "tender and sincerely expressive"[11]) Leipzig: Verlag von Friedrich Hofmeister, c1906

- "Verlungene Weise" (Lost melody) Leipzig: Verlag von Friedrich Hofmeister, c1915

- "Vöglein im Birkenbaum aus König Elfs Lieder" (The Elf King) Stuttgart: Verlag der Ebner'schen Hof-Musikalienhandlung, n.d.; New York: Luckhardt & Belder, c1906[26]

- "Waldeinsamkeit" (In the woods; text by E. Buek) New York: Luckhardt & Belder, c1907[26]

- "Weisse Wolken" (White clouds) Leipzig: Verlag von Friedrich Hofmeister, c1914

Selective list of unpublished solo songs

- "Fitzebutze" ("a jolly little child's play song") [18]

- "Teufelslied" (Devil's song)[6]

- "Vaters Wiebenlied" (Father's lullaby; "a striking specimen [of Haile's humorous songs] is Richard Dehmel's grotesque parody of the conventional cradle song, as attempted by an impatient...father"[3])

- "Verrat"

- "Wenn Dich Dein Heiland frägt" (If thy Saviour asks; poem by Julius Stum; "profoundly impressive in its simple fervor"[3])

Published duets

- "Reigen"[11]

- "Ring, Ring, Ringelein"[11]

- "Verspatung" (text from Des Knaben Wunderhorn)[11]

Stage works

- Harald der Geiger[1] (opera)

- Viola d'Amore (opera)

- The Happy Ending (musical setting for a play), premiered New York City, August 21, 1916

- Harold's Dream (opera), performed in Woodstock, New York on June 30, 1933

References

- "Haile, Eugen." Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians. 8th ed. New York: Schirmer Books, 2001.

- Anon. (1917). "Eugen Haile: the New Yorker who preserves the tradition of the German lied." [?] Opinion [unreadable], (New York) July, 1917.

- Von Ende, Amelia. "Calls music back to its simple purity of past: Tonal art must retrace its steps, maintains Eugen Haile, to pass the dangerous climax now reached in its development - would restore unselfish creative joy to composer". Musical America. (New York) 1/9/1915.

- Moderwell, H. K. "Happy Ending proves beginning of career: Eugen Haile, composer, at last gains the recognition for which he has been striving for many long years." New York [?] [unreadable]. 8/10/1916.

- "German folksong recital." Musical America (New York), 12/16/1911.

- "Eugen Haile, pianist-composer." The Musical Courier (New York). 12/27/1911.

- Haile, Eugen or Elise. Blank envelope with return address, c.1905-c.1930. From New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Eugen Haile Papers.

- "Van Yorx sings Haile's songs." Musical America (New York), Nov. 23, 1907.

- "[?] to sing Haile's songs: Theodore Van Yorx to introduce young composer's work." Musical America (New York). Nov. 7, 1907.

- Moderwell, H. K. "Giving music in the theater position of rightful dignity: Way open, contends Eugen Haile, for American composer to enlarge his audience a hundred times over in providing poetical plays with serious musical background - his own experience with a play of this nature - a field of broad possibilities." Musical America(New York), Aug. 19, 1916.

- "The Haile's recital: A song composer and his wife in a programme of his own compositions." New York Times. Jan. 30, 1912.

- "Recital of Haile songs." The Musical Courier. 1/17/1912.

- "Eugen Haile's compositions: second concert of original works advances interesting songs." Musical America (New York). 2/3/1912.

- "A benefit for Eugen Haile: concert of chamber music given by Ludwig Hess in Aeolian Hall." New York Times. 4/3/1913.

- Von Ende, Amelia. "Calls music back to its simple purity of past: Tonal art must retrace its steps, maintains Eugen Haile, to pass the dangerous climax now reached in its development - would restore unselfish creative joy to composer." Musical America (New York). 1/9/1915.

- "The Happy Ending." IBDB: Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved 4/5/2014 from: http://www.ibdb.com/show.php?id=4200

- "Actors honor Haile." [Unknown newspaper] (New York), [Late 1916]. [Clipping in the Eugen Haile Papers collection at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts]

- "Opera stars sing at Haile testimonial." Musical America (New York). 5/17/1917.

- Haile, Eugen. A riddle book with melodies. New York: H. W. Gray Co., 1924. Retrieved from WorldCat on April, 2014, from: http://www.worldcat.org

- "The Dream prelude to a new opera." Musical America (New York), July, 1933.

- "Eugene Haile: composer of several operas and incidental music." New York Times, 8/15/1933.

- "Haile song recital." Musical America (New York). 2/7/12.

- Verlaine, Paul; Hall, G., tr. Poems of Paul Verlaine. Chicago: Stone & Kimball, 1895.

- Haile, Eugen. Christabend: v. Doepkemeÿer für Gesang mit Klavierbegleitung. Ulm, Germany: Zu beziehen vom Komponisten, c.1900.

- Haile, Eugen. Peace. n.d. Holograph of cantata. From the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Eugen Haile Papers.

- WorlCat.org, search on "Haile, Eugen", Retrieved 4/2014.

Note: all newspaper and magazine articles referenced are available in the Eugen Haile Papers collection at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Call no. JPB 83-259 (see External Link to the catalog record, below).