Eugen Ernst

Eugen Oswald Gustav Ernst (20 September 1864 – 31 May 1954) was a German Social Democrat and Socialist politician. His appointment as President of the Police of Berlin in January 1919 prompted the Spartacist uprising in Berlin.

Eugen Ernst | |

|---|---|

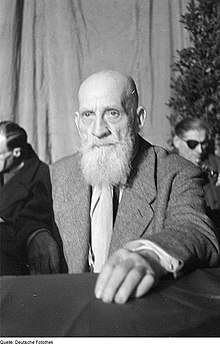

Eugen Ernst in 1946 | |

| Chairman of the SPD commission in Prussia | |

| In office 1907–1918 | |

| Prussian Minister of the Interior / Minister without portfolio | |

| In office 14 November 1918 – 25 March 1919 | |

| Member of the Weimar National Assembly | |

| In office January 1919 – June 1920 | |

| Constituency | Berlin 3 |

| President of the Police of Berlin | |

| In office 4 January 1919 – April 1920 | |

| President of the Police of Breslau | |

| In office May 1920 – September 1920 | |

| Town councillor of Werder (Havel) | |

| In office 1926–1933 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 20 September 1864 Murowana Goslin, Province of Posen, Prussia (Murowana Goślina, Poland) |

| Died | 31 May 1954 (aged 89) Werder (Havel), East Germany |

| Political party | Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) |

| Occupation | typesetter |

Biography

Eugen Ernst was born in Murowana-Goslin, Province of Posen, Prussia (now Murowana Goślina, Poland). His father was a carpenter, he attended school in Werder (Havel), was trained as a typesetter and worked for a book printer until 1892.[1]

Ernst joined the bookprinters union in 1884 and became a member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) in 1884[2] or 1886.[3] He soon held several positions as a party official and was the chairman of the intraparty oppositional "Youth" from 1891 to 1893. He served as the SPD's steward for the constituency of Berlin 6 from 1897 to 1900 and again from 1902 to 1905. In 1902/1903 he was the business executive of the socialdemocrat Vorwärts printing house and its custodian from 1903 to 1918. From 1900 to 1901 and 1917 to 1919 Ernst was a member of the SPDs' party board. Ernst was chairman of the Prussian SPD commission from 1907 to 1918 and headed the SPD electoral committee for Greater Berlin from 1915 to 1917.[3]

In November 1918 Ernst became a member of the Soldiers and workers' council of Greater Berlin. He is either described as Minister of the Interior[2] or Minister without portfolio in the Prussian Council of the People's Deputies under Paul Hirsch.[4]

On 4 January 1919, after the Independent Social Democratic (USPD) members of the Prussian Council of the People's deputies had left the people's council, Ernst was appointed President of the Police of Berlin by the Prussian government. His predecessor, Emil Eichhorn, was the last member of the USPD holding an influential position in Berlin. Eichhorn, who worked for the Russian Telegraph Agency in Berlin,[5] had supported the Volksmarinedivision in the Skirmish of the Berlin Schloss in December 1918 and was dismissed from his post with the approval of the Central Workers and Soldiers council. Eichhorn however refused to accept his dismissal and kept his office at Berlin's police headquarters. He was supported by armed groups of revolutionaries when Ernst appeared at the Police headquarter at Alexanderplatz. The following day a large protest demonstration against the dismissal of Eichhorn was organized by several left-wing groups, which led to the Spartacist uprising.[6][7][8]

In the 1919 German federal election Ernst was elected as a member of the Weimar National Assembly representing the Berlin 3 constituency.[2]

Ernst was criticized for his inactivity as the head of Berlin's Police forces during the Kapp Putsch of March 1920 and lost his position as Berlin's President of the Police in April 1920.[9][10]

In May 1920 Ernst became President of the Police of Breslau, but was dismissed in September 1920 after local protesters had attacked the French and the Polish consulate in Breslau on 26 August 1920. From 1926 to 1933 he was town councilor in Werder (Havel).[2]

After World War II Ernst rejoined the Social Democratic Party, which was merged with the Communist Party in 1946. He participated in the unification conference of April 1946 but did not play any political role at that time. Ernst died in 1954 in Werder.[2]

Publications

- Polizeispitzeleien und Ausnahmegesetze, 1878–1910, Berlin, 1911[11]

- Ein Leben für die Arbeiterbewegung, 1946[3]

References

- Vierhaus, Rudolf (2006). biography (in German). Munich: Deutsche Biographische Enzyklopädie, Bd. 3. p. 137. ISBN 978-3-598-25033-0.

- Kotowski, Georg. "Biography" (in German). Neue Deutsche Biographie.

- "Personendaten" (in German). GESIS – Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences.

- "Der Freistaat Preußen - Die Staatsministerien 1918–1933" (in German). gonschior.de.

- Wofgang, Malanowski (2 December 1968). "Kartoffeln – Keine Revolution" (in German). Der Spiegel.

- Kellerhoff, Sven Felix; Keil, Lars-Broder (6 January 2019). "Der linke Polizeipräsident begann den Spartakusaufstand" (in German). Die Welt.

- Orlow (1986). Weimar Prussia, 1918 – 1925 The unlikely rock of democracy. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 59 ff. ISBN 0-8229-3519-8.

- Moore, Barrington jr. (1978). Injustice – the Social Bases of Obedience and Revolt. p. 306. ISBN 978-08-7332-145-7.

- Orlow, Dietrich (1978). Preußen und der Kapp-Putsch (pdf) (in German). Munich: Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte. pp. 201, 223.

- Fowkes, Ben (2014). The German Left and the Weimar Republic. Leiden: Brill. p. 82. ISBN 978-90-04-21029-5.

- Liang, Hsi-Huey (1977). Die Berliner Polizei in der Weimarer Republik (in German). Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyther. p. 6. ISBN 3-11-006520-7.

External links