Eucalyptus eugenioides

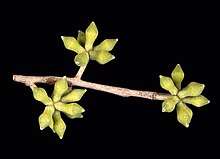

Eucalyptus eugenioides, commonly known as the thin-leaved stringybark or white stringybark,[2] is a species of tree endemic to eastern Australia. It is a small to medium-sized tree with rough stringy bark, lance-shaped to curved adult leaves, Flower buds in groups of between nine and fifteen, white flowers and hemispherical fruit.

| Thin-leaved stringybark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Blue Mountains National Park, Australia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Myrtales |

| Family: | Myrtaceae |

| Genus: | Eucalyptus |

| Species: | E. eugenioides |

| Binomial name | |

| Eucalyptus eugenioides | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

List

| |

Description

Eucalyptus eugenioides is a tree that typically grows to a height of 25–30 m (82–98 ft) and forms a lignotuber. Its trunk is 70 cm (28 in) wide at chest height and has rough, stringy, grey to reddish bark. Young plants and coppice regrowth have egg-shaped to lance-shaped leaves 45–80 mm (1.8–3.1 in) long and 15–35 mm (0.59–1.38 in) wide, glossy green on the upper surface and distinctly paler below. Adult leaves are more or less the same glossy green on both sides, lance-shaped to curved, 70–160 mm (2.8–6.3 in) long and 9–35 mm (0.35–1.38 in) wide on a petiole 6–20 mm (0.24–0.79 in) long. The flower buds are arranged in leaf axils in groups of nine to fifteen, on an unbranched peduncle 5–17 mm (0.20–0.67 in) long, the individual buds on a pedicel 1–5 mm (0.039–0.197 in) long. Mature buds are green to yellow, oval to spindle-shaped, 6–8 mm (0.24–0.31 in) long and 3–4 mm (0.12–0.16 in) wide with a conical to beaked operculum. Flowering occurs from July to January. The fruit is a woody, hemispherical or shortened spherical capsule 4–6 mm (0.16–0.24 in) long and 6–10 mm (0.24–0.39 in) wide with the valves near rim level or slightly beyond.[2][3][4][5]

Taxonomy

Eucalyptus eugenioides was first formally described in 1827 by Kurt Sprengel from an unpublished description by Franz Sieber and the description was published in Sprengel's book, Systema Vegetabilium.[6][7] The species name refers to its percived similarity to trees of the genus Eugenia.[2][5] The term "stringybark" refers to the long, thin bark fibres that can be pulled off the tree trunk in strings.[8]

Distribution and habitat

The thin-leaved stringybark is found across eastern New South Wales from Wyndham north to the vicinity of Warwick in southeastern Queensland with scattered populations further north as far as Gladstone.[5][3] It is a common tree of shale- and slate-derived, moderately fertile soils in lowlands and low hills. It grows in open forest with other trees such as grey box (E. moluccana), forest red gum (E. tereticornis), cabbage gum (E. amplifolia), manna gum (E. viminalis), woollybutt (E. longifolia), narrow-leaved ironbark (E. crebra), and argyle apple (E. cinerea), spotted gum (Corymbia maculata), and with paperbark species such as prickly paperbark (Melaleuca styphelioides) and white feather honeymyrtle (M. decora).[5][9] The thin-leaved stringybark is one of the key canopy species of the threatened Cumberland Plain Woodlands.[10][11]

Ecology

The thin-leaved stringybark regenerates by regrowing from epicormic buds after bushfire and can live for more than a hundred years.[9] The longhorn beetle species Adrium artifex has been recorded from the thin-leaved stringybark.[12]

Cultivation

Eucalyptus eugenioides has been grown in California, where it grows best in coastal areas.[13] In New South Wales, it is also known as "good kind stringybark" by beekeepers as the bees feeding on it are healthy and produce honey with a well-balanced amino-acid profile. It also provides the last crop of pollen before winter.[14]

References

- "Eucalyptus eugenioides". Australian Plant Census. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- "Eucalyptus eugenioides". Euclid: Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Hill, Ken. "Eucalyptus eugenioides". Royal Botanic Garden Sydney. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- Chippendale, George M. "Eucalyptus eugenioides". Australian Biological Resources Study, Department of the Environment and Energy, Canberra. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- Boland, Douglas J.; Brooker, M. I. H.; Chippendale, G. M.; McDonald, Maurice William (2006). Forest trees of Australia. Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing. p. 304. ISBN 0-643-06969-0.

- "Eucalyptus eugenioides". APNI. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- Sprengel, Kurt (1827). Systema Vegetabilium (Volume 4). New York: Sumtibus Librariae Dieterichianae. p. 195. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- Walters, Brian (November 2009). "ANPSA Plant Guide: Eucalyptus, Corymbia and Angophora - Background". Australian Native Plants Society (Australia). Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- Benson, Doug; McDougall, Lyn (1998). "Ecology of Sydney plant species:Part 6 Dicotyledon family Myrtaceae" (PDF). Cunninghamia. 5 (4): 809–987. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-06-14.

- Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (20 June 2011). "Cumberland Plain Woodlands". Australian Government. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- Les Robinson - Field Guide to the Native Plants of Sydney, ISBN 978-0-7318-1211-0 page 45

- Hawkeswood, Trevor J. (1993). "Review of the biology, host plants and immature stages of the Australian Cerambycidae (Coleoptera). Part 2, Cerambycinae (Tribes Oemini, Cerambycini, Hesperophanini, Callidiopini, Neostenini, Aphanasiini, Phlyctaenodini, Tessarommatini and Piesarthrini" (PDF). Giornale Italiano Di Entomologia. 6: 313–55. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2011-09-06.

- McMinn, H.E.; Mamo (1969) [1937]. Pacific Coast Trees. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 313.

- Honeybee Australis (2010). "Thin-leaf stringybark". Beekeeping in Australia. Retrieved 7 September 2011.