Étude

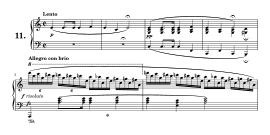

An étude (/ˈeɪtjuːd/; French: [e.tyd], meaning 'study') is an instrumental musical composition, usually short, of considerable difficulty, and designed to provide practice material for perfecting a particular musical skill. The tradition of writing études emerged in the early 19th century with the rapidly growing popularity of the piano. Of the vast number of études from that era some are still used as teaching material (particularly pieces by Carl Czerny and Muzio Clementi), and a few, by major composers such as Frédéric Chopin, Franz Liszt and Claude Debussy, achieved a place in today's concert repertory. Études written in the 20th century include those related to traditional ones (György Ligeti) and those that require wholly unorthodox technique (John Cage).

19th century

Studies, lessons, and other didactic instrumental pieces composed before the 19th century are extremely varied, without any established genres. Domenico Scarlatti's 30 Essercizi per gravicembalo ("30 Exercises for harpsichord", 1738) do not differ in scope from his other keyboard works, and J.S. Bach's four volumes of Clavier-Übung ("keyboard practice") contain everything from simple organ duets to the extensive and difficult Goldberg Variations.

The situation changed in the early 19th century. Instruction books with exercises became very common. Of particular importance were collections of "studies" by Johann Baptist Cramer (published between 1804 and 1810), early parts of Muzio Clementi's Gradus ad Parnassum (1817–26), numerous works by Carl Czerny, Maria Szymanowska's Vingt exercises et préludes (c. 1820), and Ignaz Moscheles' Studien Op. 70 (1825–26). However, with the late parts of Clementi's collection and Moscheles' Charakteristische Studien Op. 95 (1836–37) the situation began to change, with both composers striving to create music that would both please the audiences in concert and serve as a good teaching tool. Such a combination of didactic and musical value in a study is sometimes referred to as a concert study.

The technique required to play Chopin's Études, Op. 10 (1833) and Op. 25 (1837) was extremely novel at the time of their publication; the first performer who succeeded at mastering the pieces was the renowned virtuoso composer Franz Liszt (to whom Chopin dedicated the Op. 10). Liszt himself composed a number of études that were more extensive and even more complex than Chopin's. Among these, the most well-known is the collection Études d'Execution Transcendante (final version published in 1852). These did not retain the didactic aspect of Chopin's work, however, since the difficulty and the technique used varies within a given piece. Each of the études has a different character, designated by its name: Preludio; Molto Vivace; Paysage / Landscape; Mazeppa; Feux Follets - Irrlichter/ Will-o'-the-wisp ; Vision; Eroica; Wilde Jagd/ Wild Hunt; Ricordanza; Allegro Molto Agitato; Harmonies du Soir/ Evening Harmonies; and Chasse-neige / Snow-whirls.

The 19th century also saw a number of étude and study collections for instruments other than the piano. Guitarist composer Fernando Sor published his 12 Studies, op. 6 for guitar in London as early as 1815. These works all conform to the standard definition of 19th-century étude in that they are short compositions, each exploiting a single facet of technique. Collections of studies for flute were published during the second half of the 19th century by Ernesto Köhler, Wilhelm Popp and Adolf Terschak.

20th century

The early 20th century saw the publication of a number of important collections of études. Claude Debussy's Études for piano (1915) conform to the "one facet of technique per piece" rule, but exhibit unorthodox structures with many sharp contrasts, and many concentrate on sonorities and timbres peculiar to the piano, rather than technical points. Leopold Godowsky's 53 Studies on the Chopin Études (1894–1914) are built on Chopin's études: Godowsky's additions and changes elevated Chopin's music to new, hitherto unknown levels of difficulty. Other important études of this period include Heitor Villa-Lobos' virtuoso 12 Études for guitar (1929) and pieces by Russian composers: Sergei Rachmaninoff's Études-Tableaux (1911, 1917) and several collections by Alexander Scriabin (all for piano).

By mid-century the old étude tradition was largely abandoned. Olivier Messiaen's Quatre études de rythme ("Four studies in rhythm", 1949–50) were not didactic compositions, but experiments with scales of durations, as well as with dynamics, figurations, coloration, and pitches. John Cage's études—Études Australes (1974–75) for piano, Études Boreales (1978) for cello and/or piano and Freeman Études (1977–80, 1989–90) for violin—are indeterminate pieces based on star charts, and some of the most difficult works in the repertory. The three books of Études by György Ligeti (1985, 1988–94, 1995) are perhaps closest to the old tradition in that they too concentrate each on a particular technique. Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji's Études transcendantes (100) (1940–44), which take Godowsky and Liszt as their starting point, frequently focus on particular technical elements, as well as various rhythmical difficulties.[1][2] William Bolcom was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his Twelve New Etudes for Piano in 1988.

See also

- List of étude composers

- Music written in all 24 major and minor keys

- Invention (musical composition)

References

- Fredrik Ullén. "100 Transcendental Etudes (1940–44)". The Sorabji Archive. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

- Marc-André Roberge. "Notes on the Études transcendantes". Sorabji Resource Site. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

Further reading

- Ferguson, Howard; Hamilton, Kenneth L. (2001). "Study". In Root, Deane L. (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Oxford University Press.

| Look up étude in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |