Esterka

Esterka refers to a mythical Jewish mistress of Casimir the Great, the historical King of Poland who reigned between 1333 and 1370. Medieval Polish and Jewish chroniclers considered the legend as historical fact and report a wonderful love story between the beautiful Jewess and the great monarch.[1]

Legend

The first account of Esterka can be found in scripts of the 15th-century Polish chronicler Jan Długosz and recorded again, a century later, by the famous Jewish chronicler David Gans, who even maintained that Esterka was married to the king.[2] Gans wrote:

"Casimir, the king of Poland, took for himself a concubine - a young Jewess named Esther. Of all the maidens of the land, none compared to her beauty. She was his wife for many years. For her sake, the king extended many privileges to the Jews of his kingdom. She persuaded the king to issue documents of freedom and beneficence."[3]

According to the legend, Esterka was the daughter of a poor tailor from Opoczno named Rafael. Her beauty[4] and intelligence were legendary. She was later installed in the royal palace of Lobzovo near Krakow.[5]

Esterka was said to have played a significant role in Casimir's life. In the legend, she performed as a King's adviser in support of various initiatives: free trade, building stone cities, tolerance to representatives of different religious faiths and support of cultural development. Casimir was loyal to the Jews and encouraged them. For many years, Krakow was the home of one of the most important Jewish communities in Europe.[5] He was called The Great King for his intelligence and bright vision, which helped him to increase the size and wealth of Poland. During the years of the Black Death Esterka's influence helped to prevent the murder of many Polish Jews who were scapegoated for the disease.

King Casmir had several wives, but Esterka was said to have been the only one who gave him male offspring despite the fact that they never were officially married. Their sons, Pelko and Nemir, were said in the legend to have been baptized on the request of their father. The two became the mythical ancestors of several Polish noble families. To develop legal and commercial relations between Jews, Poles, and Germans, Pelko was sent to Kraków. In 1363, Nemir was sent to Ruthenia to establish a new knightly order, which later became the patrimonial nest of the Rudanovsky dynasty [6] She also had two daughters brought up as Jews.[5]

After Casimir's death, his nephew Louis of Hungary became the King of Poland. During his reign, riots broke out against the Jews, especially violent in Krakow. According to the legend, rioters broke into Esterka's palace in Lobzovo and murdered her and her two daughters.[5] Rudanovsky from Rudawa River was considered Esterka's burial.

Places

Esterka House

Seweryn Udziela Ethnographic Museum in Kraków is located at Krakowska street 46.[7]

Wawel Castle

Several places such as villages, streets and monuments in Poland are named after Esterka including a street in Cracow[8] and usually ones associated with her and the King. In some sources Esterka is presented as King's consort who actually lived with him at Wawel Castle.

Royal Palace in Łobzów

King Cazimir built a fortalicium on the trade route leading to Silesia. It was a castle with a tower whose function was to defend the city from the north. But according to the legend, the King built it for his beloved Esterka.

Esterka Mound

Esterka Mound was situated on Rudawa river, more than 3 km to the northwest of Wawel Hill in the gardens of the royal palace at Łobzów. The mound was excavated at the end of 18th century on the initiative of King Stanisław August Poniatowski in the belief that it would contain Esterka's medieval grave. The mound was completely destroyed in the 1950s during the construction of a sports stadium.[9]

Royal Palace in Łobzów

Royal Palace in Łobzów Esterka Mound

Esterka Mound

In modern culture

Historical Mural

The mural at Joseph Street introduced in 2016. It portrays associated with the district: King Kazimierz the Great and Esterka.

Historical Mural at Joseph Street

Historical Mural at Joseph Street Casimir the Great and Esterka mural

Casimir the Great and Esterka mural

In literature

- Marcin Bielski “Kronika wszystkiego świata” (Chronicle of everything in the World) (1551)[10]

- David Gans Chronicle (1595)[11]

- Józef Ignacy Kraszewski "Król chłopów" (Peasant King), Book Six[11]

- Yitshak ben Moshe Rumsch "The Book of Esther the Second" (1883)[11]

- Shmuel Yosef Agnon "In Esterka's House"[11]

- Karl Emil Franzos "Esterka Regina" (The Queen Esterka) in "The Jews of Barnow" (1872)[11]

- Aaron Zeitlin "Esterke" (1932)[11]

- Thaddeus Bulgarin “Esterka” (1828)[12]

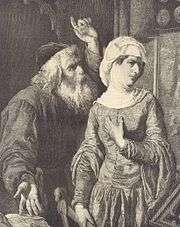

In art

- Franciszek Żmurko – "Casimir the Great and Esterka" (1891)

- Wandalin Strzałecki – "Casimir the Great and Esterka" (1879, lost)

- Władysław Łuszczkiewicz – "Casimir the Great visiting Esterka"

- Maurycy Gottlieb – "Esterka and King Casimir" (1879)[11]

In historical works

- Simon Dubnow – "History of the Jews in Russia and Poland" (1916)[13]

- Chone Shmeruk[14] – "The Esterke Story in Yiddish and Polish Literature"[15]

References

- Sherwin, Byron L. (1997-04-24). Sparks Amidst the Ashes: The Spiritual Legacy of Polish Jewry. Oxford University Press. p. 125. ISBN 9780195355468.

- Haya, Bar-Itzhak - Professor of Hebrew and Comparative Literature and Head of Folklore Studies, University of Haifa. "YIVO | Esterke". yivoencyclopedia.org. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. Retrieved 2018-12-30.

The earliest written version of the Esterke legend by a Jewish author appears in David Gans's sixteenth-century chronicle, Tsemaḥ David. Gans wrote that Casimir, King of Poland, took as his concubine a Jewish girl named Esther, a maiden whose beauty was unparalleled in the entire country, and she was his wife for many years. The King performed great favors for the Jews for her sake, and she extracted from the king writs of kindness and liberty for the Jews.

- Sherwin, Byron L. (1997). Sparks Amidst the Ashes: The Spiritual Legacy of Polish Jewry. Oxford University Press. p. 126. ISBN 9780195106855.

1370. Casimir, the king of Poland, took for himself a concubine - a young Jewess named Esther. Of all the maidens of the land, none compared to her beauty. She was his wife for many years. For her sake, the king extended many privileges to the Jews of his kingdom. She persuaded the king to issue documents of freedom and beneficence.

- Przyjaciel ludu: czyli, tygodnik potrzebnych i pożytecznych wiadomości [A friend of the people: a weekly of vital and useful news] (in Polish). Leszno: Nakładem i drukiem E. Günthera. 1840. p. 139.

Estera was a Jewess; she had to be beautiful..

- "Remembering Esterka". jewishpress.com/.

- "The American Association for Polish-Jewish Studies - Nathan Cohen Esterka". aapjstudies.org.

- "The Seweryn Udziela Museum of Ethnography in Krakow". museums.krakow.travel.

- A : akcent (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Lubelskie. 1998.

One of Krakow's streets is named Ester after Esterka.

- The Archaeology of Early Medieval Poland

- "Polona". polona.pl. Retrieved 2018-12-29.

Kazimierz chował miłośnicę z Czech Rokiczankę, która była niepospolitej cudowności, ale nią potem wzgardził, a Esterkę Żydówkę na jej miejsce wziął

- The Jew's Daughter: A Cultural History of a Conversion Narrative (Efraim Sicher)

- Pamiętnik literacki: czasopismo kwartalne poświęcone historii i krytyce literatury polskiej [Diary of literature] (in Polish). Zakład im. Ossolińskich. 1988. p. 312.

- "Prof. Chone Shmeruk". academy.ac.il. Retrieved 2018-12-30.

- Shmeruk, Chone (1985). The Esterke Story in Yiddish and Polish Literature: A Case Study in the Mutual Relations of Two Cultural Traditions. Zalman Shazar Center for the Furtherance of the Study of Jewish History. ISBN 9789652270245.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Esterka (mistress). |