Essenbæk Abbey

Essenbæk Abbey (Essenbæk Kloster) was a Benedictine monastery located in Essenbæk Parish eight kilometers east of Randers and 1.7 kilometer north of Assentoft.

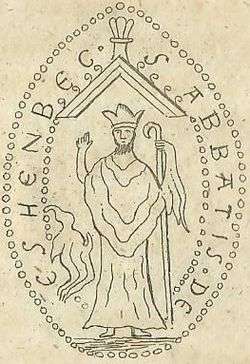

Abbot Jonas of Essenbæk Abbey's, and thus probably also the abbey’s own, seal from 1490, representing the abbot and by his right side a praying person in monastic cowl.[1] | |

Location within Denmark | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Order | Benedictine |

| Established | Ca. 1140 |

| Disestablished | 1548 |

| Diocese | Aarhus |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Stig Tokesen “Hvide” |

| Site | |

| Location | Randers Municipality, Central Denmark Region, Denmark |

| Coordinates | 56.451917°N 10.136028°E |

| Visible remains | none |

| Public access | no |

History

Early history

The monastery was established by Stig Tokesen ”Hvide”, who was killed in 1151,[2] and was then perhaps a Cluniac double monastery in or by Randers. In 1179 it was modified, perhaps by its nuns getting Our Lady Abbey in the town, and was moved the next year to the east of the drumlin Holmen[3] in Essenbæk Parish,[4] after which it was named.[5] It is said that Stig Tokesen ”Hvide” and his wife Margrethe were buried in the monastery's church.[2]

The Annals of Essenbæk, with historical notices regarding the years 1020-1323, seem to have been written in Essenbæk Abbey,[6] which was the only monastery in Djursland until the 20th century.[7]

In 1330 Stig Andersen "Hvide” bought for a farm in Egens burial places[8] in the monastery's church[2] for his wife and he, and in 1369 he was buried there.[8] Also the wife Tove Andersdatter was buried in the church.[2]

September 28, 1403 the monastery was referred to as “Saint Lawrence’s monastery in Æssumbæk of the order of Saint Benedict”,[9] and some of the monastery's income was from pilgrims[8] who Saint John's Eve went on pilgrimage[10] to the Well of Saint Lawrence (Sankt Laurseskilde)[8] below Assentoft.[11]

In 1431 the pope challenged the monastery's monks by letting the bishop of Viborg examine the by them elected abbot's qualifications, before the bishop ordained the abbot as such.[12]

Much wealth was donated to the monastery, particularly by the Hvide clan,[13] so that in time it owned all real estate in Essenbæk Parish, almost all real estate in Virring Parish,[14] and furthermore estates in the parishes of Albæk, Bregnet, Dalbyover, Egens, Egå, Fausing, Fløjstrup, Gimming, Gjesing, Glesborg, Harridslev, Homå, Hornslet, Hørning, Kastbjerg, Lime, Mariager, Mejlby, Mørke, Rimsø, Skødstrup, Tøstrup, Udbyneder, Voldby, Ødum, and Årslev, as well as in the hundreds of Hjelmslev, Houlbjerg, and Middelsom.[4] The monastery's estate in Sønderhald Hundred[15] was at the latest from August 9, 1475, in the form of the judicial district of Essenbæk,[16] legally separated from the hundred.[17]

For six farms the monastery in 1516 bought itself free from billeting, and in 1518 the king owed the monastery 38 weights (0.56 kilograms) of silver and 25 Rhenish guilder.[18] In 1525 it was assessed to raise from its estate two horsemen for domestic service, and two horsemen as well as two riflemen for foreign service.[19]

Despite the wealth the king declared September 5, 1529[20] that the courtier Hans Emmiksen by the monastery's monks was elected,[5] rather than its infirm abbot, as its custodian until his death, since “the monastery’s estate is daily won from it, and the brothers for a long time have not gotten their necessities according to their rule’s exercise”.[4] Hans Emmiksen was at the same time named as vassal there by the king,[18] who rather than the monks themselves[15] probably prompted the election.[21] In the monastery's home farm alone there were then 20 oxen with two plows, 27 large and small steers, 42 cows, 26 heifers and young cattle, 100 sheep, 53 swine, eight old nags, and 13 young nags and yearlings (year-old colts and fillies).[22]

Modern history

A monk from the monastery was beheaded in 1537 for rape,[21] and in 1540 the monastery was confiscated by the king.[23] Around that time it was mortgaged to Axel Juul for 3,000 dollars – a sum that in 1546 had been increased to 4,000 dollars.[20] The monks left the monastery early,[23] and April 3, 1548 the king decided that it should be a part of Queen Dorothea’s jointure. He therefore paid the mortgage,[15] but later she got instead Sønderborg and Nordborg as jointure,[24] and in 1550 the monastery was incorporated into Dronningborg Fief.[25] Hans Stygge, who was vassal there, got the bodies of Stig Tokesen ”Hvide”[26] and his wife Margrethe[2] moved to Randers Castle Chapel,[26] and Bjørn Andersen, who owned Stenalt, got the bodies of Stig Andersen “Hvide”[27] and Tove Andersdatter moved to Ørsted Church.[2]

In 1558 Chancellery Secretary Jakob Reventlow registered nearly 100 letters from Essenbæk Abbey in Silkeborg’s archive. Some few of them are now in the Danish National Archives, but the others are since lost.[28]

It is not known when the monastery was torn down,[29] but in 1593 the local judicial district bailiff Rasmus Pedersen resided in Essenbæk Home Farm on the west of Holmen, which is why the monastery was probably uninhabitable then.[30] The church's bell was taken to Old Essenbæk Church.[31] August 22, 1661 i.a. the monastery was acquired from the king by Hans Friis, and that estate then included e.g. a chapel[32] which perhaps was a remnant of the monastery's church.[33] December 20, 1687 the judicial district was incorporated into Sønderhald Hundred.[34]

Teacher Karl Hansen wrote in 1832[35] that there were no remains of the monastery,[36] but in 1894 a piece of solid wall was found on the west of the mound Kirkegaarden (the Churchyard) on Holmen, which was then being surveyed for the National Museum of Denmark. Teacher J. V. Nissen lead in 1898 an excavation for the National Museum of Denmark, by which e.g. remains of the monastery's church were unearthed,[37] and the National Museum of Denmark therefore prompted the preservation of the site. Kirkegaarden's owner began, though, in 1918 to remove stones from there,[38] since the preservation had not been written on either deed or mortgage records,[39] so Architect I. P. Hjersing mapped[7] in 1925 what remained before that too was removed. The same year the owner found a stone-lined well there, and many skeletons around it.[38]

Known abbots

Location and structure

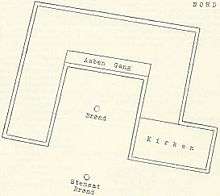

Holmen is mostly sandy soil between bog and meadow[47] south of Randers Fjord.[7] Kirkegaarden on it was in 1894 ca. two alen (1.26 meter) high, ca. 37 alen (23.23 meters) from north to south, and ca. 50 alen (31.39 meters) from east to west. The excavation in 1898 unearthed there a one foot to two feet (0.31 to 0.63 meter) high as well as four feet and six inches (1.41 meter) thick foundation of raw[37] boulders, down to 130 centimeters below the surface of the earth,[38] which several places were laid around driven down oak piles.[7] Down to 85 centimeters below the surface of the earth[38] there was on top of the foundation remnants of a wall core of smaller fieldstones and brick fragments in ample lime, which was covered with large medieval bricks. When the monastery was torn down, the large medieval bricks were first removed, after which the wall core was toppled outward. Pieces of the toppled wall were till then up to seven alen (4.39 meters) high, but on top there was probably courses entirely of brick.[48]

The foundation was of a building's north-eastern corner, which was ended flatly toward east,[7] and inside it was 30 feet (9.42 meters) on each side. Nearby remains indicated that the foundation was continued toward north from the building's north-west, which is why the building probably was the church's chancel.[48]

The mapping in 1925 indicated that the foundation north of the church's chancel was of the monastery's 49 meters long and 10 meters wide eastern wing, which was divided into four rooms.[7] The sacristy was apparently nearest the church.[49] The mapping indicated also that the eastern wing was built to the monastery's northern wing,[7] in which there probably was a ca. two and a half alen (1.57 meter) wide open cloister. Also the monastery's western wing was indicated,[50] and between the wings there was a courtyard which was open toward south,[38] with a stone-lined well in the middle and buried skeletons around.[39] Straight in front of the courtyard was another stone-lined well[38] – this with stairs. Altogether the monastery was measured to be ca. 57 meters from north to south and 47 meters from east to west.[11]

In 1529 there was kitchen, priest kitchen, scullery, basement, a food loft and a granary in the monastery, as well as perhaps rooms for labourers and guests, and the monastery owned a home farm with a flour house.[51]

On a plot of heavy boulders north of the monastery stood a watermill,[38] and curved around east of the monastery was a ditch with water. South-west of the monastery was its fishpond.[48]

From the monastery lead a road across the bog to a ca. 40 square meters flat space at the bottom of[10] the gully Lausdal,[52] where at the Well of Saint Lawrence there was a stone wall, and where in 1850 was found a 10 alen (6.28 meters) long tree pump. In the beginning of the 18th century were also found skeletons in walled and at the top vaulted graves on the location, which consequently was the monastery's graveyard,[10] and again late in the 18th century[36] as well as in 1849.[53]

Through the meadow the road was paved with smaller cobblestones and large rim stones, but was wound from there as a sunken lane up through the heather hills at Assentoft.[7] A stone-lined road also lead through the meadow from the monastery to its loading port[38] by Gudenåen.[48]

On the clay hill[38] Mondal south of the bog,[54] and east of Lausdal,[10] remains found of large medieval bricks indicate that the bricks for the monastery and its brick-lined graves were produced in a brickyard there.[38]

Anna Krabbe’s Columns

Two three and a half meters high[55] granite columns[56] from the park at Stenalt[55] were taken in 1804 across the frozen Randers Fjord[57] to Dronningborg.[58] There a local farmer used the one as roller, but in 1870 the columns were bought by Randers Municipality, which in 1872 got them erected in Tøjhushaven in Randers.[57]

Hewn in the columns is[58] "1589", a coat of arms and "FAK".[56] Probably in that year they were erected at Stenalt, which was then owned by the lady (fruen) Anna Krabbe,[57] whose family's coat of arms it was.[58] She collected antiquities, and is said to have gotten the columns brought there from Essenbæk Abbey.[56]

The columns were probably quarried in the fourth century[57] in Egypt, and thereafter probably stood in a Roman building. They were probably erected in Essenbæk Abbey when it was built, and then probably got new capitals from Denmark added.[59]

References

- Hansen, Karl (1832). Danske Ridderborge, beskrevne tildeels efter utrykte Kilder. Copenhagen, Denmark; Hofboghandler Beekens Forlag, pp. 136-137

- Nielsen, Allan Berg (1984). Essenbæk gamle kirke in Årsskrift 1984. Auning, Denmark: Lokalhistorisk forening for Sønderhald Kommune og Sønderhald Egnsarkiv, p. 18

- Lorenzen, Vilhelm (1933). De danske benediktinerklostres bygningshistorie. Copenhagen, Denmark: G. E. C. Gad, pp. 92-96

- Nielsen, Niels; Skautrup, Peter; Mathiassen, Therkel (1963). J. P. TRAP: DANMARK. FEMTE UDGAVE. REDIGERET AF NIELS NIELSEN • PETER SKAUTRUP • THERKEL MATHIASSEN. RANDERS AMT. BIND VII, 2. Copenhagen, Denmark: G. E. C. Gads Forlag, p. 848

- Rasmussen, Poul (1958). Essenbæk Klosters jordegods i Sønder Hald herred in HISTORISK AARBOG FRA RANDERS AMT 1958. Randers, Denmark; Randers Amts historiske Samfund, p. 20

- Skov, Sigvard, Preben (1937). Essenbækaarbogen in Jyske Samlinger. Aarhus, Denmark; Jysk Selskab for Historie, Sprog og Litteratur, pp. 100-101

- Lorenzen, Vilhelm (1933). De danske benediktinerklostres bygningshistorie. Copenhagen, Denmark: G. E. C. Gad, p. 96

- Møller, Mogens (2016). Grenå og omegn under fremmede herrer. Copenhagen, Denmark; BoD – Books on Demand, p. 155

- Hedemann, Markus; Knudsen, Anders Leegaard; Hansen, Thomas (2010). nr. 14030928002 in Diplomatarium Danicum. http://diplomatarium.dk/ [Retrieved 2016-07-30]

- Mariager, Rasmus (1937). ESSENBÆK SOGNS HISTORIE: SAMLET OG UDGIVET AF R. Mariager. Odder, Denmark; Duplikeringsbureauet, p. 9

- Nielsen, Niels; Skautrup, Peter; Mathiassen, Therkel (1963). J. P. TRAP: DANMARK. FEMTE UDGAVE. REDIGERET AF NIELS NIELSEN • PETER SKAUTRUP • THERKEL MATHIASSEN. RANDERS AMT. BIND VII, 2. Copenhagen, Denmark: G. E. C. Gads Forlag, p. 849

- Lorenzen, Vilhelm (1933). De danske benediktinerklostres bygningshistorie. Copenhagen, Denmark: G. E. C. Gad, p. 323

- Caspersen, Erling (1977). Det forsvundne Essenbæk Kloster in Årsskrift 1977. Auning, Denmark; Lokalhistorisk Forening for Sønderhald Kommune, p. 28

- Rasmussen, Poul (1958). Essenbæk Klosters jordegods i Sønder Hald herred in HISTORISK AARBOG FRA RANDERS AMT 1958. Randers, Denmark; Randers Amts historiske Samfund, p. 24

- Rasmussen, Poul (1958). Essenbæk Klosters jordegods i Sønder Hald herred in HISTORISK AARBOG FRA RANDERS AMT 1958. Randers, Denmark; Randers Amts historiske Samfund, p. 21

- Lerdam, Henrik (2004). Birk, lov og ret: Birkerettens historie i Danmark indtil 1600. Copenhagen, Denmark: Museum Tusculanums Forlag. ISBN 978-87-7289-974-9, p. 104

- Blangstrup, Christian (1930). Salmonsens konversationsleksikon. Anden Udgave. Bind III: Benzolderivater-Brides. Copenhagen, Denmark; A/S J. H. Schultz Forlagsboghandel, p. 270

- Hansen, Karl (1832). Danske Ridderborge, beskrevne tildeels efter utrykte Kilder. Copenhagen, Denmark; Hofboghandler Beekens Forlag, p. 138

- Mehlsen, Ejnar (1919). Essenbæk Kloster in Aarbog udgivet af Randers Amts Historiske Samfund. Årgang 13. 52-60. Randers, Denmark: Randers Amts Historiske Samfund, p. 57

- Erslev, Kristian (1879). DANMARKS LEN OG LENSMÆND I DET SEXTENDE AARHUNDREDE (1513-1596). Copenhagen, Denmark; Jacob Erslevs Forlag, p. 154

- Daugaard, Jacob Brøgger (1830). Om de danske klostre i middelalderen. Copenhagen, Denmark; Andreas Seidelin, p. 407

- Rasmussen, Poul (1958). Essenbæk Klosters jordegods i Sønder Hald herred in HISTORISK AARBOG FRA RANDERS AMT 1958. Randers, Denmark; Randers Amts historiske Samfund, p. 28

- Mariager, Rasmus (1937). ESSENBÆK SOGNS HISTORIE: SAMLET OG UDGIVET AF R. Mariager. Odder, Denmark; Duplikeringsbureauet, p. 11

- Hansen, Karl (1832). Danske Ridderborge, beskrevne tildeels efter utrykte Kilder. Copenhagen, Denmark; Hofboghandler Beekens Forlag, p. 140

- Caspersen, Erling (1977). Det forsvundne Essenbæk Kloster in Årsskrift 1977. Auning, Denmark; Lokalhistorisk Forening for Sønderhald Kommune, p. 27

- Mehlsen, Ejnar (1919). Essenbæk Kloster in Aarbog udgivet af Randers Amts Historiske Samfund. Årgang 13. 52-60. Randers, Denmark: Randers Amts Historiske Samfund, p. 54

- Hansen, Karl (1832). Danske Ridderborge, beskrevne tildeels efter utrykte Kilder. Copenhagen, Denmark; Hofboghandler Beekens Forlag, p. 135

- Jexlev, Thelma (1977). VEJLEDENDE ARKIVREGISTRATURER XVIII. LOKALARKIVER TIL 1559. GEJSTLIGE ARKIVER II: Odense stift, jyske stifter og Slesvig stift. Copenhagen, Denmark; Rigsarkivet, p. 226

- Jakobsen, Johnny Grandjean Gøgsig (2008). KlosterGIS DK in HisKis Årsskrift 2008. Historisk-Kartografisk InformationsSystem, p. 44 http://hiskis2.dk/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/HisKIS-2008.pdf (Retrieved 2016-11-06)

- Hansen, Karl (1832). Danske Ridderborge, beskrevne tildeels efter utrykte Kilder. Copenhagen, Denmark; Hofboghandler Beekens Forlag, p. 141

- Hansen, Karl (1832). Danske Ridderborge, beskrevne tildeels efter utrykte Kilder. Copenhagen, Denmark; Hofboghandler Beekens Forlag, p. 134

- West, F. J. (1908). Kronens Skøder: paa afhændet og erhvervet Jordegods i Danmark, fra Reformationen til Nutiden. Andet Bind. 1648-1688. Copenhagen, Denmark; Rigsarkivet, p. 101

- Rasmussen, Poul (1958). Essenbæk Klosters jordegods i Sønder Hald herred in HISTORISK AARBOG FRA RANDERS AMT 1958. Randers, Denmark; Randers Amts historiske Samfund, p. 105

- Nielsen, Niels; Skautrup, Peter; Mathiassen, Therkel (1963). J. P. TRAP: DANMARK. FEMTE UDGAVE. REDIGERET AF NIELS NIELSEN • PETER SKAUTRUP • THERKEL MATHIASSEN. RANDERS AMT. BIND VII, 2. Copenhagen, Denmark: G. E. C. Gads Forlag, p. 841

- Nielsen, Allan Berg (1984). Essenbæk gamle kirke in Årsskrift 1984. Auning, Denmark: Lokalhistorisk forening for Sønderhald Kommune og Sønderhald Egnsarkiv, p. 19

- Hansen, Karl (1832). Danske Ridderborge, beskrevne tildeels efter utrykte Kilder. Copenhagen, Denmark; Hofboghandler Beekens Forlag, p. 131

- Mehlsen, Ejnar (1919). Essenbæk Kloster in Aarbog udgivet af Randers Amts Historiske Samfund. Årgang 13. 52-60. Randers, Denmark: Randers Amts Historiske Samfund, pp. 52-53

- Mariager, Rasmus (1937). ESSENBÆK SOGNS HISTORIE: SAMLET OG UDGIVET AF R. Mariager. Odder, Denmark; Duplikeringsbureauet, p. 13

- Mariager, Rasmus (1937). ESSENBÆK SOGNS HISTORIE: SAMLET OG UDGIVET AF R. Mariager. Odder, Denmark; Duplikeringsbureauet, p. 79

- Hansen, Karl (1832). Danske Ridderborge, beskrevne tildeels efter utrykte Kilder. Copenhagen, Denmark; Hofboghandler Beekens Forlag, p. 136

- Andersen, Aage (1998). Diplomatarium Danicum VI: 1396-1398. Copenhagen, Denmark: Det Danske Sprog- og Litteraturselskab, p. 43

- Hedemann, Markus; Knudsen, Anders Leegaard; Hansen, Thomas (2010). nr. 14230717001 in Diplomatarium Danicum. http://diplomatarium.dk/ [Retrieved 2016-07-30]

- Hedemann, Markus; Knudsen, Anders Leegaard; Hansen, Thomas (2010). nr. 14240904001 in Diplomatarium Danicum. http://diplomatarium.dk/ [Retrieved 2016-07-30]

- Lorenzen, Vilhelm (1933). De danske benediktinerklostres bygningshistorie. Copenhagen, Denmark: G. E. C. Gad, s. 25

- Mariager, Rasmus (1937). ESSENBÆK SOGNS HISTORIE: SAMLET OG UDGIVET AF R. Mariager. Odder, Denmark; Duplikeringsbureauet, p. 10-11

- Hansen, Karl (1832). Danske Ridderborge, beskrevne tildeels efter utrykte Kilder. Copenhagen, Denmark; Hofboghandler Beekens Forlag, pp. 136-138

- Mariager, Rasmus (1937). ESSENBÆK SOGNS HISTORIE: SAMLET OG UDGIVET AF R. Mariager. Odder, Denmark; Duplikeringsbureauet, p. 10

- Mehlsen, Ejnar (1919). Essenbæk Kloster in Aarbog udgivet af Randers Amts Historiske Samfund. Årgang 13. 52-60. Randers, Denmark: Randers Amts Historiske Samfund, p. 53

- Lorenzen, Vilhelm (1933). De danske benediktinerklostres bygningshistorie. Copenhagen, Denmark: G. E. C. Gad, p. 326

- Lorenzen, Vilhelm (1933). De danske benediktinerklostres bygningshistorie. Copenhagen, Denmark: G. E. C. Gad, pp. 96-97

- Lorenzen, Vilhelm (1933). De danske benediktinerklostres bygningshistorie. Copenhagen, Denmark: G. E. C. Gad, p. 97

- Sønderhald Egnsarkiv. LAUSDAL, SLUGT VED SOFIEKLOSTER. https://arkiv.dk/vis/2167729 [Retrieved 2016-11-13]

- Caspersen, Erling (1977). Det forsvundne Essenbæk Kloster in Årsskrift 1977. Auning, Denmark; Lokalhistorisk Forening for Sønderhald Kommune, p. 26

- Mariager, Rasmus (1937). ESSENBÆK SOGNS HISTORIE: SAMLET OG UDGIVET AF R. Mariager. Odder, Denmark; Duplikeringsbureauet, pp. 76-77

- Caspersen, Erling (1977). Det forsvundne Essenbæk Kloster in Årsskrift 1977. Auning, Denmark; Lokalhistorisk Forening for Sønderhald Kommune, p. 24

- Strange, Preben (1985). Flere søjler fra Essenbæk kloster in Årsskrift 1985. Auning, Denmark; Lokalhistorisk forening for Sønderhald Kommune og Sønderhald Egnsarkiv, p. 24

- Foreningen HistoriskAtlas.dk (2005). AnnaKrabbes Søjler. http://historiskatlas.dk/Anna_Krabbes_S%C3%B8jler_(8578) [Retrieved 2016-10-29]

- Sørensen, Lone Hammer (14.06.2016). Assentoft kæmper for at få antikke søjler hjem fra Randers in Randers Amtsavis. Randers, Denmark; Jysk Fynske Medier

- Strange, Preben (1985). Flere søjler fra Essenbæk kloster in Årsskrift 1985. Auning, Danmark; Lokalhistorisk forening for Sønderhald Kommune og Sønderhald Egnsarkiv, p. 25