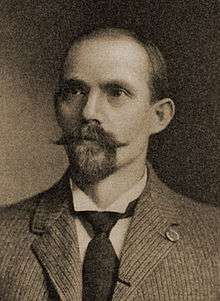

Ernest Untermann

Gerhard Ernest Untermann, Sr. (1864–1956) was a German-American seaman, socialist author, translator, newspaper editor. In his later life he was Director of the old Washington Park Zoo in Milwaukee, a geologist, fossil hunter, and artist.

Biography

Early years

Ernest was born in Brandenburg, Prussia (Germany) on November 6, 1864. He studied geology and paleontology at the University of Berlin. Upon graduation, he later recalled that he was "drafted into the great army of the unemployed before I had done a stroke of useful work. Society had trained me for intellectual tasks, but had failed to provide for employment."[1] Untermann took work as a deckhand on a German steamer sailing to New York City, and thus he was exposed to America for the first time. Untermann subsequently took several trips around the world working on German, Spanish, and American sailing vessels.[2] In the course of his nautical adventures, Untermann was shipwrecked three times, thus exposing him to life in the Philippine Islands and China firsthand. In the third incident, he narrowly escaped with his life when his own vessel went down in the North Sea.[3]

Following these events, Untermann was briefly in the German military, an interlude which he later recalled to be decisive in his political radicalization:

"I had learned the truth of economic determinism and of the class struggle without knowing these terms. But I still clung to the illusion of patriotism. The drillmasters of Billy the Versatile cured me of that. The class line in all its brutal nakedness became visible to me. The tyrannical and insolent arrogance of the demigods with shoulder straps roused my spirit of independence to its climax. An affront, a blow, a courtmartial, closed my military career and fixed in my mind one aim — the abolition of the ruling class."[4]

Untermann briefly returned to the University of Berlin for post graduate courses, but later said this only "showed me the rottenness of the intellectual elite of Germany."[5] Still, it was at this time that Untermann first came into contact with the Social Democratic newspaper Vorwärts ("Forward") and various other Marxist books and leaflets, which gave concrete political form to his emerging radicalism.[6]

Untermann emigrated to America and joined the merchant marine, spending the next 10 years on board ships plying the South Seas trade routes. He became a US citizen in 1893.

Socialist years

Untermann was a member of the Socialist Labor Party of America (SLP) in the 1890s before leaving to join the Socialist Party of America (SPA).

Untermann was a regular contributor to Algie Simons' dissident SLP newspaper The Workers Call, published in Chicago. When Simons moved to Chicago to assume the editorship of International Socialist Review in 1900, a monthly published by the pioneer American Marxist publishing house, Charles H. Kerr & Co., Untermann became a frequent contributor to that publication as well. Untermann earned his keep as an associate editor for J.A. Wayland's mass circulation socialist weekly, The Appeal to Reason in 1903.

Untermann was the first American translator of Karl Marx's Das Kapital, beginning work on the massive project in the spring of 1905 while living on a chicken farm in Orlando, Florida and completing translations of volumes 2 and 3 for Kerr in 1907 and 1909, respectively.[7] He also translated other socialist works for an American audience, including the memoirs of Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel as well as The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, by Frederick Engels. In addition to translations from German and Italian, Untermann wrote original works on Economics and Natural History. Untermann's books included Science and Revolution (1905), The World's Revolutions (1906), Marxian Economics: A Popular Introduction to the Three Volumes of Marx's Capital (1907).

Untermann professed an adherence to the thinking of Karl Kautsky and Joseph Dietzgen. He held that science had a class basis and drew very radical conclusions from this premise without hesitation or pulling of punches, writing in his 1905 book, Science and Revolution, that

"I speak as a proletarian and a socialist. I make no pretense to be a scientist without class affiliation. There has never been any science which was not made possible, and which was not influenced, by the economic and class environment of the various scientists. I am, indeed, aware of the fact that there are certain general facts in all sciences which apply to all mankind regardless of classes. But I am also aware of the other fact, that the concrete application of any general scientific truth to different historical conditions and men varies considerably, because abstract truths have a general applicability only under abstract conditions, but are more or less modified in the contact with concrete environments."[8]

Untermann further indicated that "bourgeois science" was perpetually under assault in capitalist society and that "university professors have learned to their bitter disappointment that freedom of science is little respected when it runs counter to freedom of trade." Hence:

"Under these circumstances, the proletariat cannot place any reliance on bourgeois science. it must and will maintain a critical attitude toward all bourgeois science, and accept nothing that does not stand the test of proletarian standards.

"So far as bourgeois science coincides with the findings of proletarian science, we shall gladly accept and foster every truth... But we shall on our part reject everything which tends to strengthen the ruling class, endanger the progress of the proletarian revolution, or interfere with the advance of human knowledge and control of natural forces in general."[9]

Rather unsurprisingly, his Science and Revolution was translated into Russian and published in Soviet Ukraine in 1923.

Untermann was on the National Executive Committee of the Socialist Party of America from 1908–10 and was the Socialist candidate for Governor of Idaho in 1908 and 1910 and for US Senate from California in 1912. He believed strongly in support of the affiliated unions of the AF of L and opposed to the more radical approach of the Industrial Workers of the World. His anti-syndicalist perspective became more pronounced over time, with Untermann declaring in a polemic 1913 article that a crisis approached during which "it will be impossible to avoid the expulsion of individuals who through word and deed confess that they are not in harmony with the fundamental principles of the [socialist] organization."[10]

Untermann was a delegate to the 1910 "National Congress" and 1912 National Convention of the Socialist Party, chairing the organization's Committee on Immigration.[11] He was a chief author, along with Joshua Wanhope (1863-1945), of a resolution on immigration which was pro-exclusionary — called "racist" by its critics — backing the AF of L in its desire to stop manufacturers from importing cheap, non-union labor from the Far East. Untermann and Wanhope were joined as a majority on this point by journalist Robert Hunter and J. Stitt Wilson of California.[12]

John Spargo, Meyer London, and Leo Laukki (1880-1938) were the minority on this committee, opposing exclusionism. Untermann and Wanhope's majority proposal was effectively killed by the convention on motion by Charles Solomon of New York not to receive the committee's report, but rather to hold the matter open for further investigation and final decision by the next party convention, scheduled for four years hence.[13]

Untermann later served as Foreign Editor of Victor Berger's socialist daily, the Milwaukee Leader, beginning in 1921. Untermann wrote editorials relating to international affairs for the publication, with editorials on domestic affairs written by John M. Work.[14]

Post-radical years

Untermann was also a painter of great accomplishment, specializing in landscapes and prehistoric flora and fauna. He was known as "The Artist of the Uintas." He contributed paintings, murals, and panels to the Dinosaur National Monument, the old Utah Field House of Natural History State Park Museum and has a large collection of paintings at the new Utah Field House of Natural History State Park Museum in Vernal, Utah. His interest in paleontology and Geology led to his moving to Vernal, Utah.[15]

Untermann died in Vernal on January 5, 1956.

Untermann's papers are housed at two institutions, the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison, Wisconsin and the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Footnotes

- Ernest Untermann, "How I Became a Socialist, The Comrade, v. 2, no. 3 (Dec. 1903), p. 62.

- Untermann, "How I Became a Socialist," p. 62.

- Untermann, "How I Became a Socialist," p. 63.

- Untermann, "How I Became a Socialist," p. 63

- Untermann, "How I Became a Socialist," p. 63.

- Untermann, "How I Became a Socialist," p. 62.

- Allen Ruff, "We Called Each Other Comrade," Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1997; p. 90.

- Ernest Untermann, Science and Revolution. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1905; p. 6.

- Ernest Untermann, Science and Revolution, pp. 154-155.

- Ernest Untermann, "No Compromise with the IWW," St. Louis Labor, whole no. 624 (Jan. 18, 1913), pg. 7.

- Ernest Untermann, "A Reply to Debs," Social-Democratic Herald [Milwaukee], Wisconsin Edition, vol. 13, no. 16, whole no. 629 (Aug. 20, 1910), pg. 2.

- Mark Pittenger, American Socialists and Evolutionary Thought, 1870-1920. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1993; p. 179.

- John Spargo (ed.), National Convention of the Socialist Party Held at Indianapolis, Ind., May 12 to 18, 1912: Stenographic Report by Wilson E. McDermut, assisted by Charles W. Phillips. Chicago: The Socialist Party, 1912; pp. 166-167.

- John M. Work, "The Leader Among Labor Dailies: Milwaukee's Paper is Rightly Named," The Labor Age, v. 12, no. 8 (October 1923), pg. 10.

- Swanson, Vern G.; Robert S. Olpin; and William C. Seifrit, Utah Painting and Sculpture. Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith, Publisher, 1997.

Works

Books and pamphlets

- Municipality: From Capitalism to Socialism. Girard, KS: Appeal to Reason, 1902.

- Religion and Politics. Girard, KS: Appeal to Reason, c. 1904.

- Socialism: A New World Movement. Girard, KS: Appeal to Reason, 1904.

- Science and Revolution. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1905.

- Socialism vs. Single Tax: A Verbatim Report of a Debate held at Twelfth Street, Turner Hall, Chicago, December 20th, 1905. With Louis F. Post. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., n.d. [1906].

- The World's Revolutions. (1906) Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1909.

- Marxian Economics: A Popular Introduction to the Three Volumes of Marx's Capital. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1907.

- Die Logischen Mängel des Engeren Marxismus. Georg Plechanow et alii gegen Josef Dietzgen. Berlin: Verlag der Dietzgenschen Philosophie, 1910.

- Popular Guide to the Geology of Dinosaur National Monument.

Articles

- "The American Farmer and the Socialist Party," The Socialist [Seattle], part 1: whole no. 143 (May 3, 1903), pg. 2; part 2: whole no. 144 (May 10, 1903), pg. 2; part 3: whole no. 145 (May 17, 1903), pp. 2, 4; part 4: whole no. 147 (May 31, 1903), pg. 2. part 5: whole no. 149 (June 14, 1903), pg. 2; part 6: whole no. 153, pg. 3.; part 7 (conclusion): whole no. 156 (August 5, 1903), pg. 2.

- "How I Became a Socialist," The Comrade, v. 2, no. 3 (Dec. 1903), p. 62.

- "The Third Volume of Marx's Capital," International Socialist Review, vol. 9, no. 6 (June 1909), pp. 946–958.

- "A Reply to Debs," Social-Democratic Herald [Milwaukee], Wisconsin Edition, vol. 13, no. 16, whole no. 629 (Aug. 20, 1910), pg. 2.

- "The Immigration Question," Social-Democratic Herald [Milwaukee], vol. 13, no. 32, whole no. 645 (Dec. 10, 1910), pg. 2.

- "No Compromise with the IWW," St. Louis Labor, whole no. 624 (Jan. 18, 1913), pg. 7.

Translations

- Wilhelm Liebknecht, Karl Marx: Biographical Memoirs. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1901.

- Frederick Engels, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1902.

- Wilhelm Bölsche, The Evolution of Man. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1905.

- Joseph Dietzgen, The Positive Outcome of Philosophy. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1906.

- Enrico Ferri, The Positive School of Criminology: Three Lectures Given at the University of Naples, Italy, on April 22, 23, and 24, 1901. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1906.

- M. Wilhelm Meyer, The Making of the World. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1906.

- August Bebel, Bebel's Reminiscences. New York: Socialist Literature Co., 1911.