Ernest Ouandié

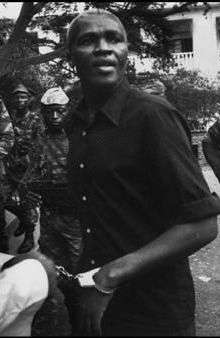

Ernest Ouandié (1924 – 15 January 1971) was a leader of the struggle for independence of Cameroon in the 1950s who continued to resist the government of President Ahmadou Ahidjo after Cameroon became independent in 1960. He was captured in 1970, tried and condemned to the death penalty. On 15 January 1971, he was publicly executed in Bafoussam.

Ernest Ouandié | |

|---|---|

Ernest Ouandié on 15 January 1971, before being executed | |

| Born | 1924 Badoumla, Bana, West Cameroon |

| Died | 15 January 1971 (aged 46) Bafoussam. Cameroon |

| Nationality | Cameroon |

| Occupation | Teacher |

| Known for | Executed for treason |

Early years

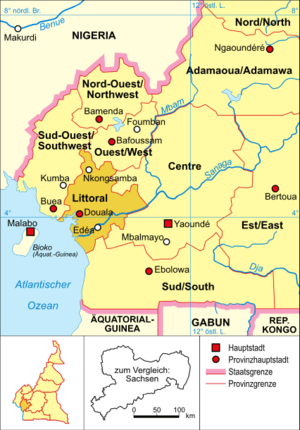

Ernest Ouandié was born in 1924 in Badoumla, Bana district in Haut-Nkam in a Bamiléké family.[1][2] He attended public school in Bafoussam, and then l'Ecole Primaire Supérieure de Yaoundé where he obtained a Diplôme des Moniteurs Indigènes (DMI) in November 1943 and began work as a teacher. In 1944 he joined the Union of Confederate Trade-Unions of Cameroon, affiliated with the French General Confederation of Labour (CGT).[1] From 1944 to 1948, Ernest Ouandié taught at Edéa. On 7 October 1948, he was posted to Dschang. A month later, he was posted to Douala as director of the New-Bell Bamiléké public school.[3]

In 1948 Ouandié became a member of the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon (Union des Populations du Cameroun – UPC), a left-wing pro-independence political party. He was elected vice-president of the UPC four years later.[1] In September 1953 he was assigned to Doumé and Yoko in Mbam-et-Kim. In December 1954 he was posted to Batouri, then Bertoua. Finally, in January 1955 he was assigned to Douala again.[3] He attended the World Congress of Democratic Youth in China in December 1954, and also travelled to Paris and Moscow.[1]

Guerilla Fighter

In April and May 1955 the UPC held a series of militant meetings, circulated pamphlets and organised strikes.[4] On 20 June 1955 the UPC leader, Ruben Um Nyobé, was sentenced in his absence to six months in prison and a large fine. On 13 July 1955 the French government of Edgar Faure dissolved the UPC by decree. Most of the UPC leaders moved to Kumba in the British-administered Southern Cameroons to avoid being jailed by the colonial power.[5] Armed revolution broke out in Cameroon.[6] Ruben Um Nyobé remained in the French zone in the forest near his home village of Boumnyébel, where he had taken refuge in April 1955.[5] This village lies just east of the Sanaga-Maritime area of the Littoral province on the road connecting Edéa to Yaoundé, the capital.[7] The UPC nationalist rebels conducted a fierce struggle against the French, who fought back equally ruthlessly. The insurgents were forced to take refuge in the swamps and forests. Ruben Um Nyobé was cornered in the Sanaga-Maritime area and killed on 13 September 1958.[8]

Ouandié had taken refuge in Kumba in 1956. In July 1957, under pressure from the French, the British authorities in western Cameroon deported Ernest Ouandié and other leaders of the UPC to Khartoum, Sudan. He then moved in turn to Cairo, Egypt, to Conakry, Guinea and finally to Accra, Ghana.[3] After Cameroon gained independence in 1960, UPC rebels who had been fighting the French colonial government continued to fight the government of President Ahmadou Ahidjo, whom they considered to be a puppet of the French.[9] Ahidjo had asked the French to lend troops to keep the peace during and after the transition to democracy. Led by General Max Briand, who had served previously in Algeria and Indochina, these troops conducted a pacification campaign in the Bamiléké territory of the West, Centre and Littoral provinces. The campaign featured human rights abuses from all sides. During the UPC insurrection against both the French and Cameroonians, most sources place the death toll in the tens of thousands.[10][11][12] Some sources go higher and place the death toll in the hundreds of thousands.[13][14]

In 1960 Ouandié, Félix-Roland Moumié, Abel Kingué and other UPC leaders were exiled, isolated and desperate.[15] The UPC leadership was increasingly involved in factional squabbles, out of touch with what was happening in Cameroon.[16] Moumié was poisoned by French agents using thallium on 13 October 1960 and died on 4 November 1960, leaving Ouandié as head of the UPC.[17] On 1 May 1961 the military tribunal in Yaoundé condemned Oaundié and Abel Kingué (in their absence) to deportation.[18] That year Ouandié returned secretly from Accra to Cameroon to work towards the overthrow of the Ahidjo regime.[16] The Southern Cameroons (now the Southwest and Northwest regions) gained independence from the British and joined a loose federation with East Cameroon on 1 October 1961.[19] Abel Kingué died in Cairo on 16 June 1964, leaving Ouandié the last member of the original leadership. President Ahidjo declared that Ouandié was public enemy number one.[20]

Led by Ouandié, guerrilla warfare against the Ahidjo regime by the Armée de libération nationale Kamerounaise (ANLK) continued throughout the 1960s, with the zones of activity gradually becoming depopulated and the guerrilla numbers slowly dwindling.[21] The rebel leader Tankeu Noé was captured and executed. In January 1964, public executions of fifteen captured rebels were staged in Douala, Bafoussam and Edéa as part of the celebrations of the fourth anniversary of independence. Meanwhile, the UPC members in exile were locked in a power struggle that caused Ouandié and his maquis to increasingly fear betrayal, while the government used the fear of the rebel forces to justify increasing the security forces occupying the Bamiléké towns and villages.[22] The guerrillas lived a hunted life and were often short of food. A surviving member of the rebel force said that they did not do much fighting except in the kitchen.[21]

Capture and execution

Albert Ndongmo, also a Bamiléké, was made Bishop of Nkongsamba in 1964 in a diocese contained within the zone of guerrilla operations.[23] By Ndongmo's account, in 1965 President Ahmadou Ahidjo asked him to try to mediate with Ouandié to try to end the fighting. In the following years Ndongmo had a series of meetings with the rebels. In 1970 Ouandié called for help, and Ndongmo picked him up in his car and took him to his own house, where he let him stay for several nights. Ndongmo claimed that his actions were consistent with President Ahidjo's instructions, but it seems clear that he sympathised strongly with the rebels although he did not approve of their methods.[9] Ndongmo was called to go to Rome to answer some questions about business dealings, but before leaving he sent Ouandié and his secretary to take refuge with his catechist on the outskirts of Mbanga. The catechist refused to accept Oaundie, and alerted the police.[24]

Ouandié and the secretary went on the run, but were in unfamiliar territory and were hunted by the local people as well as the police. Disagreeing over directions, they parted company. Ouandié tried to hide in the banana plantations, even under bridges, but was hopelessly lost.[24] On 19 August 1970 Ouandié surrendered to the authorities near the town of Loum.[25] Exhausted, thirsty, hungry and disoriented, he had asked a passer-by for help. The man recognised him and led him towards a nearby gendarmerie. When they neared the building and Ouandié recognised his situation, he abandoned his guide and simply walked into the post and told them who he was. At first the officers panicked and fled, but then returned and called for help. Ouandié was taken by helicopter to Yaoundé and imprisoned.[24]

Ndongmo was arrested when he returned from Rome.[9] On 29 August the Cameroon Times ran a lead story titled "Bishop Ndongmo arrested for alleged subversion." The paper also reported that Ouandie had given in to government forces. The reporter, editor and publisher of the paper were arrested, tried and convicted by a military tribunal on charges of publishing false information. The court said that the term "give in" could be taken to mean that the government was unable to catch Ouandié, which would tend to undermine and ridicule the government. The court said that he had been captured.[26] Ouandié was tried in December 1970 and condemned to death. He was executed by firing squad on 15 January 1971 at Bafoussam.[16]

In France, most of the major media (AFP, Le Monde...) reproduce without hindsight the version presented by Ahmadou Ahidjo's government. On the other hand, Henri Curiel's Solidarity network is very active, mobilising lawyers and intellectuals to try to organise the legal and media defence of the accused, and approaching French diplomats to convince them to intervene. An International Committee for the Defence of Ernest Ouandié is formed, chaired by the naturalist Theodore Monod. Despite the lack of interest from the media, several personalities joined the committee: former minister Pierre Cot, writer Michel Leiris, philosopher Paul Ricœur and linguist Noam Chomsky. In the Thomson-CSF plant in Villacoublay, dozens of workers have signed a petition of support.[27]

Legacy

Bishop Ndongmo was also tried for treason by a military tribunal in January 1971, found guilty and sentenced to death by firing squad. However, the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, and he was sent to a prison camp in Tcholliré. Ndongmo was pardoned in 1976 on condition that he leave the country.[9]

In January 1991 on the weekend following the 20th anniversary of Ouandié's death there were moves by opposition groups to lay flowers on the place where he had died. The Governor of Western Province told the population to remain at home, troops were placed on alert and security stepped up throughout Bafoussam, particularly around the place where Ouandié's was executed. According to one account, "The forces of law and order, alerted by the gathering crowds, descended on the site, dispersing the crowd and seizing the bouquets of flowers. [Some people] were arrested by soldiers and taken to the office of the provincial Governor; there they were interrogated."[28] After a change of policy, on 16 December 1991 Ouandié was declared a national hero by the parliament of Cameroon.[3]

In January 2012 the reconstituted Union des Populations du Cameroun (UPC) protested that Ouandié's grave had been desecrated. The UPC recalled that he had been designated a National Hero by the act of 1991, and said some minimum level of security should have been provided for his grave.[29] The grave was untended and the right side of the tomb was broken. However, it is possible that the damage to the tomb had been done by Ouandié's family in a ritual common to that part of the country.[30]

References

Citations

- AbandoKwe 2012.

- Bouopda 2008b, p. 49.

- Nkwebo 2010.

- Bouopda 2008, p. 93.

- Bouopda 2008, p. 94.

- Asong & Chi 2011, p. 99.

- Prévitali 1999, p. 62.

- Mukong 2008, p. 30.

- Gifford 1998, p. 254-256.

- Johnson, Willard R. 1970. The Cameroon Federation; political integration in a fragmentary society. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Africa (1981)

- "WHPSI": The World Handbook of Political and Social Indicators by Charles Lewis Taylor

- Malaquais 2002, p. 319-320.

- Bouopda 2008, p. 155.

- Bouopda 2008b, p. 82.

- Bouopda 2008, p. 97.

- Beti & Tobner 1989, p. 170.

- Bouopda 2008b, p. 96.

- Zewde 2008, p. 54.

- Prévitali 1999, p. 201.

- Njassep 2012.

- Prévitali 1999, p. 200.

- Messina & Slageren 2005, p. 375.

- Mukong 2008, p. 32-33.

- Anyangwe 2008, p. 90.

- Anyangwe 2011, p. 97-98.

- Thomas Deltombe, Manuel Domergue, Jacob Tatsita, Kamerun !, La Découverte, 2019

- Mbembé 2001, p. 119.

- Petsoko 2012.

- Le Messager 2012.

Sources

- AbandoKwe, Juliette (16 January 2012). "41 ans après: Ernest Ouandié, "le dernier des Mohicans", exécuté le 15 janvier 1971". Togoforum (in French). Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anyangwe, Carlson (1 August 2008). Imperialistic Politics in Cameroun: Resistance & the Inception of the Restoration of the Statehood of Southern Cameroons. African Books Collective. ISBN 978-9956-558-50-6. Retrieved 27 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anyangwe, Carlson (14 November 2011). Criminal Law in Cameroon. Specific Offences. African Books Collective. ISBN 978-9956-726-62-2. Retrieved 27 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Asong, Linus; Chi, Simon Ndeh (15 May 2011). Ndeh Ntumazah: A Conversational Auto Biography. African Books Collective. ISBN 978-9956-579-32-7. Retrieved 27 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bouopda, Pierre Kamé (April 2008). Cameroun du protectorat vers la démocratie: 1884–1992 (in French). Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-19604-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beti, Mongo; Tobner, Odile (1989). Dictionnaire de la Négritude (in French). Éd. L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-7384-0494-7. Retrieved 29 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bouopda, Pierre Kamé (2008b). De la rébellion dans le Bamiléké (in French). L'Harmattan. p. 49. ISBN 978-2-296-05236-9. Retrieved 29 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gifford, Paul (1998). African Christianity: its public role. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33417-6. Retrieved 27 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Le Messager (16 January 2012). "Sacrilège. La tombe d'Ernest Ouandié profanée à Bafoussam". Cameroon Voice (in French). Retrieved 27 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Malaquais, Dominique (2002). Architecture, pouvoir et dissidence au Cameroun (in French). KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 978-2-84586-231-9. Retrieved 28 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mbembé, J.-A. (17 June 2001). Mbembe. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20434-8. Retrieved 27 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Messina, Jean-Paul; Slageren, Jaap Van (2005). Histoire du christianisme au Cameroun: des origines à nos jours : approche oecuménique (in French). KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 978-2-84586-687-4. Retrieved 28 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mukong, Albert (29 December 2008). Prisoner Without a Crime: Disciplining Dissent in Ahidjo's Cameroon. African Books Collective. ISBN 978-9956-558-34-6. Retrieved 27 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Njassep, Matthieu (January 2012). "HOMMAGE À ERNEST OUANDIÉ". Camer.be (in French). Retrieved 27 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nkwebo, Denis (17 February 2010). "Ernest Ouandié : Le "maquisard" promu héros national". Quotidien Le jour – Cameroun (in French). Retrieved 27 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Petsoko, Mathurin (19 January 2012). "Profanation de la tombe d'Ernest Ouandié: La réaction de l'UPC". Journal de Cameroon (in French). Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Prévitali, Stéphane (1999). Je me souviens de Ruben: Mon témoignage sur les maquis du Cameroun, 1953–1970 (in French). KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 978-2-86537-807-4. Retrieved 28 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zewde, Bahru (2008). Society, State, and Identity in African History. African Books Collective. ISBN 978-99944-50-25-1. Retrieved 28 July 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)