E-reader

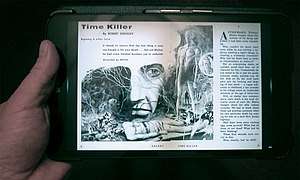

An e-reader, also called an e-book reader or e-book device, is a mobile electronic device that is designed primarily for the purpose of reading digital e-books and periodicals.[1]

Any device that can display text on a screen may act as an e-reader; however, specialized e-reader devices may optimize portability, readability, and battery life for this purpose. Their main advantages over printed books are portability, since an e-reader is capable of holding thousands of books while weighing less than one book, and the convenience provided due to add-on features.[2]

Overview

An e-reader is a device designed as a convenient way to read e-books. It is similar in form factor to a tablet computer[3], but features electronic paper rather than an LCD screen. This yields much longer battery life — the battery can last for several weeks — and better readability, similar to that of paper even in sunlight.[4] Drawbacks of this kind of display include a slow refresh rate and (usually) a grayscale-only display, which makes it unsuitable for sophisticated interactive applications as those found on tablets. The absence of such apps may be perceived as an advantage, as the user may more easily focus on reading.[5]

The Sony Librie, released in 2004 and the precursor to the Sony Reader, was the first e-reader to use electronic paper.[6] The Ectaco jetBook Color was the first color e-reader on the market, but its muted colors were criticized.[7]

Many e-readers can use the internet through Wi-Fi and the built-in software can provide a link to a digital Open Publication Distribution System (OPDS) library or an e-book retailer, allowing the user to buy, borrow, and receive digital e-books.[8] An e-reader may also download e-books from a computer or read them from a memory card.[9] However, the use of memory cards is decreasing as most of the 2010s era e-readers lack a card slot.[10]

History

An idea similar to that of an e-reader is described in a 1930 manifesto written by Bob Brown titled The Readies,[11] which describes "a simple reading machine which I can carry or move around, attach to any old electric light plug and read hundred-thousand-word novels in 10 minutes". His hypothetical machine would use a microfilm-style ribbon of miniaturized text which could be scrolled past a magnifying glass, and would allow the reader to adjust the type size. He envisioned that eventually words could be "recorded directly on the palpitating ether".[12]

The establishment of the E Ink Corporation in 1997 led to the development of electronic paper, a technology which allows a display screen to reflect light like ordinary paper without the need for a backlight. The Rocket eBook was the first commercial e-reader[13] and several others were introduced around 1998, but did not gain widespread acceptance. Electronic paper was incorporated first into the Sony Librie that was released in 2004 and Sony Reader in 2006, followed by the Amazon Kindle, a device which, upon its release in 2007, sold out within five and a half hours.[14] The Kindle includes access to the Kindle Store for e-book sales and delivery.

As of 2009, new marketing models for e-books were being developed and a new generation of reading hardware was produced. E-books (as opposed to e-readers) had yet to achieve global distribution. In the United States, as of September 2009, the Amazon Kindle model and Sony's PRS-500 were the dominant e-reading devices.[15] By March 2010, some reported that the Barnes & Noble Nook may have been selling more units than the Kindle in the US.[16]

Research released in March 2011 indicated that e-books and e-readers were more popular with the older generation than the younger generation in the UK. The survey, carried out by Silver Poll, found that around 6% of people over 55 owned an e-reader, compared with just 5% of 18- to 24-year-olds.[17] According to an IDC study from March 2011, sales for all e-readers worldwide rose to 12.8 million in 2010; 48% of them were Amazon Kindles, followed by Barnes & Noble Nooks, Pandigital, and Sony Readers (about 800,000 units for 2010).[18]

On January 27, 2010 Apple Inc. launched a multi-function tablet computer called the iPad[19] and announced agreements with five of the six largest publishers[20] that would allow Apple to distribute e-books.[21] The iPad includes a built-in app for e-book reading called iBooks and had the iBookstore for content sales and delivery. The iPad, the first commercially profitable tablet, was followed in 2011 by the release of the first Android-based tablets as well as LCD tablet versions of the Nook and Kindle. Unlike previous dedicated e-readers, tablet computers are multi-functional, utilize LCD touchscreen displays, and are more agnostic to e-book vendor apps, allowing for installation of multiple e-book reading apps. Many Android tablets accept external media and allow uploading files directly onto the tablet's file system without resorting to online stores or cloud services. Many tablet-based and smartphone-based readers are capable of displaying PDF and DJVU files, which few of the dedicated e-book readers can handle. This opens a possibility to read publications originally published on paper and later scanned into a digital format. While these files may not be considered e-books in their strict sense, they preserve the original look of printed editions. The growth in general-purpose tablet use allowed for further growth in popularity of e-books in the 2010s.

In 2012, there was a 26% decline in sales worldwide from a maximum of 23.2 million in 2011. The reason given for this "alarmingly precipitous decline" was the rise of more general-purpose tablets that provided e-book reading apps along with many other abilities in a similar form factor.[22] In 2013, ABI Research claimed that the decline in the e-reader market was due to the aging of the customer base.[23] In 2014, the industry reported e-reader sales worldwide to be around 12 million, with only Amazon.com and Kobo Inc. distributing e-readers globally and various regional distribution by Barnes & Noble (US/UK), Tolino (Germany), Icarus (Netherlands), PocketBook International (Eastern Europe and Russia) and Onyx Boox (China and Vietnam).[24] At the end of 2015, eMarketer estimated that there were 83.4 million e-reader users in the US, with the number predicted to grow by 3.5% in 2016.[25] In late 2014, PricewaterhouseCoopers predicted that by 2018 e-books would make up over 50% of total consumer publishing revenue in the U.S. and UK, while at that time, e-books were over 30% of the share of revenue.[26]

Until late 2013, use of an e-reader was not allowed on airplanes during takeoff and landing.[27] In November 2013, the FAA allowed use of e-readers on airplanes at all times if set to Airplane Mode, which turns all radios off. European authorities employed this guidance the following month.[28]

E-reader applications

Many of the major book retailers and third-party developers offer e-reader applications for desktops, tablets and mobile devices, to allow the reading of e-books and other documents independent of dedicated e-book devices.[29] E-reader applications are available for Mac and PC computers as well as for Android, iOS and Windows Phone devices.

Impact

The introduction of e-readers brought substantial changes to the publishing industry, also awakening fears and predictions about the possible disappearance of books and print periodicals.[30]

Criticism

The graphical design of ebooks underlies the format and technical limits of e-readers, because E-ink readers do not support color displays and they have a limited resolution and size.[31] The reading experience (readability) on E-ink displays (that are not back-illuminated) depends on the lighting condition.[31]

E-readers are usually designed to only offer access to the online shop of one provider. This structure is referred to as (digital) ecosystem and helps smaller companies (e.g. Kibano Digireader) to compete against multinational companies (like Amazon, Apple, etc.).[32] On the other hand, customers only have the possibility of purchasing books from a limited selection of ebooks in the online shop (accessible via the e-reader) and therefore do not have the possibility of purchasing e-books from the open market.[33] Because of the use of ecosystems, companies are not forced to compete against each other and therefore the cost of e-books do not decrease. With only the option of using an online shop, the social interaction of buying or borrowing a book disappears.[34]

In the EU, media products, including paper books, often have a tax reduction. Therefore, the VAT for conventional books was often lower than that of e-books. In legal terms, e-books were considered a service since it was regarded as a temporary lease of the product. Therefore, ebook prices were often similar to paper book prices, even if the production of ebooks has a lower cost.[33] In October 2018, the EU allowed its member countries to change the same VAT for ebooks as for paper books.[35]

Some readers have expressed concern about the perceived loss of freedom or privacy that comes with e-readers, namely the inability to read whatever a reader prefers without the possibility of being tracked.[36][37]

Positive aspects

E-readers can hold thousands of books limited only by their memory and use the same physical space as a conventional book. E-ink displays are not back-illuminated and therefore seem to cause no more eye strain than a traditional book and less eye strain than LCD screens, with a longer battery life.[38][39] Features such as the ability to adjust font size and spacing can help people who have difficulty reading or dyslexia. Some e-readers link to definitions or translations of key words.[40][41] Amazon notes that 85% of its e-reader users look up a word while reading.[42]

E-readers can instantly download content from supported public libraries by using apps like Overdrive and Hoopla.[43]

Popular e-readers

- Amazon (Global): Kindle, Kindle Paperwhite, Kindle Voyage, Kindle Oasis, Kindle Oasis 2

- Barnes & Noble (US/UK): Nook, Nook GlowLight, Nook GlowLight Plus

- Bookeen (France): Cybook Opus, Cybook Orizon, Cybook Odyssey, Cybook Odyssey HD FrontLight

- Kobo (Global): Kobo Touch, Kobo Glo, Kobo Mini, Kobo Aura, Kobo Aura HD

- Onyx Boox (Europe, China and Vietnam): Onyx Boox Max2, Onyx Boox Note

- PocketBook (Europe and Russia): PocketBook Touch, PocketBook Mini, PocketBook Touch Lux, PocketBook Color Lux, PocketBook Aqua

- Tolino (Germany): Tolino Shine, Tolino Shine 2 HD, Tolino Vision, Tolino Vision 2

See also

- Comparison of e-book readers

- Supporting platforms for e-book formats

- Open Publication Distribution System

References

- "Best E-Book Readers of 2017". CNET. Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- Ray, C. Claiborne (October 24, 2011). "The Weight of Memory". The New York Times. Q&A (column). p. D2.

- And the most popular way to read an e-book is. Wired. November 2010.

- Falcone, John (July 6, 2010). "Kindle vs. Nook vs. iPad: Which e-book reader should you buy?". CNet. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- The one gadget I can’t live without… is not my phone Techzim. Retrieved May 17, 2017

- "Sony LIBRIe – The first ever E-ink e-book Reader". Mobile mag. 2004-03-25. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- "Ectaco jetBook Color E-ink reader". Trusted Reviews. Retrieved June 17, 2013.

- "How to Rent or Borrow eBooks Online". www.moneycrashers.com. Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- "Everything You Need to Know About Using a MicroSD Card With Your Amazon Fire Tablet". Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- "Will Memory Cards Be Phase Out for eReaders Altogether? | The eBook Reader Blog". Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- Brown, Robert "Bob" (2009). Saper, Craig J. (ed.). The Readies. Literature by Design: British and American Books 1880–1930. Houston: Rice University Press. ISBN 9780892630226. OCLC 428926430. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- Schuessler, Jennifer (2010-04-08). "Bob Brown, Godfather of the E-Reader". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- MobileRead Wiki – Rocket eBook. Wiki.mobileread.com (2011-11-20). Retrieved on 2012-04-12.

- Patel, Nilay (November 21, 2007). "Kindle Sells Out in 5.5 Hours". Engadget.com. Archived from the original on November 23, 2007. Retrieved November 21, 2007.

- Take, First (2010-09-11). "Bookeen Cybook OPUS | ZDNet UK". Community.zdnet.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- Rodney Chan Nook outnumbers Kindle in March, says Digitimes Research, DIGITIMES, Taipei, 26 April 2010

- "E-book popularity set to increase this year". Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- "Nearly 18 Million Media Tablets Shipped in 2010 with Apple Capturing 83% Share; eReader Shipments Quadrupled to More Than 12 Million" (Press release). IDC. 10 March 2011. Archived from the original on 2014-10-28.

- "iPad – See the web, email, and photos like never before". Apple. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- "iPad iBooks app US-only, McGraw-Hill absent from Apple event". AppleInsider. January 28, 2010. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- "Apple Launches iPad". Apple.com. 2010-01-27. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- Tibken, Shara (December 12, 2012). "RIP e-book readers? Rise of tablets drives e-reader drop". CNet.

- Smith, Tony (25 January 2013). "Tablets aren't killing e‐readers, it's clog-popping wrinklies – analyst". The Register.

- The State of the e-Reader Industry in 2015 September 24, 2015

- Many Thought the Tablet Would Kill the Ereader. Why It Didn't Happen. eMarketer, February 29, 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- "In Europe, Slower Growth for e-Books". The New York Times (2014-11-12). Retrieved on 2014-12-05.

- Matt Phillips (2009-05-07). "Kindle DX: Must You Turn it Off for Takeoff and Landing?". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- "Cleared for take-off: Europe allows use of e-readers on planes from gate to gate". The Independent. London.

- "How to buy the best ebook reader - Which?". www.which.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- Ballatore, Andrea; Natale, Simone (2015-05-18). "E-readers and the death of the book: Or, new media and the myth of the disappearing medium". New Media & Society. 18 (10): 2379–2394. doi:10.1177/1461444815586984. ISSN 1461-4448.

- Benedetto, Simone; Drai-Zerbib, Véronique; Pedrotti, Marco; Tissier, Geoffrey; Baccino, Thierry (2013-12-27). "E-Readers and Visual Fatigue". PLoS ONE. 8 (12): e83676. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...883676B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083676. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3873942. PMID 24386252.

- Colbjørnsen, Terje (2014-06-10). "Digital divergence: analysing strategy, interpretation and controversy in the case of the introduction of an ebook reader technology". Information, Communication & Society. 18 (1): 32–47. doi:10.1080/1369118x.2014.924982. ISSN 1369-118X.

- Colbjørnsen, Terje (2014-04-07). "What is the VAT? The policies and practices of value added tax on ebooks in Europe". International Journal of Cultural Policy. 21 (3): 326–343. doi:10.1080/10286632.2014.904298. ISSN 1028-6632.

- Sangwan, Sunanda; Siguaw, Judy A.; Guan, Chong (2009-10-30). "A comparative study of motivational differences for online shopping". ACM SIGMIS Database. 40 (4): 28. doi:10.1145/1644953.1644957. ISSN 0095-0033.

- Ha, Thu-Huong (October 3, 2018). "The European Union has decided that ebooks are really books, after all".

- https://www.gnu.org/philosophy/the-danger-of-ebooks.en.html

- https://www.gnu.org/philosophy/ebooks.html

- Maxim, Andrei; Maxim, Alexandru (2012). "The Role of e-books in Reshaping the Publishing Industry". Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 62: 1046–1050. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.178. ISSN 1877-0428.

- Baccino, Thierry; Tissier, Geoffrey; Pedrotti, Marco; Drai-Zerbib, Véronique; Benedetto, Simone (2013-12-27). "E-Readers and Visual Fatigue". PLOS ONE. 8 (12): e83676. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...883676B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083676. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3873942. PMID 24386252.

- Barzillai, Mirit; Thomson, Jenny M. (2018-09-30). "Children learning to read in a digital world". First Monday. 23 (10). doi:10.5210/fm.v23i10.9437. ISSN 1396-0466.

- "Kindle Features: Search, X-Ray, Wikipedia and Dictionary Lookup, Instant Translations". www.amazon.com. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Kozlowski, Michael (2015-10-14). "What are the most looked up words on the Kindle?". Good e-Reader. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- "Guidemaster: Ars tests and picks the best e-readers for every budget". Retrieved 2019-05-28.

External links