Equestrian statue of Frederick V

An equestrian statue of King Frederick V of Denmark stands in the center of Amalienborg Square, Copenhagen, framed by the four symmetrical wings of the Amalienborg palace.[2] The statue portrays the king in classic attire, crowned with laurels and with his hand outstretched, holding a baton.[3] Commissioned by the Danish East India Company, it was designed in Neoclassical style by Jacques Saly in 1768 and was cast in bronze in 1771.[4] The apparent dignity and tranquility in the depiction of the king is typical of Danish representations of monarchs.[5] It is considered to be one of the notable equestrian monuments of its time.[6]

| Equestrian statue of Frederick V | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Jacques Saly |

| Year | 1768 |

| Medium | Bronze[1] |

| Subject | Frederick V of Denmark |

| Location | Copenhagen |

Background

In 1752 Saly was commissioned to create a sculpture of Frederick V on horseback, to be placed in the center of the courtyard of Amalienborg Palace. The equestrian statue was commissioned by Adam Gottlob Moltke, head of the Asiatic Company, as a gift to the king. But while Moltke’s company offered to finance the statue, it was the government who chose the sculptor. Count Johan Hartvig Ernst Bernstorff wrote to the Danish Legation secretary to the French Court in Paris, Joachim Wasserschlebe, to find a suitable French sculptor. Sculptor Edmé Bouchardon rejected the offer, but suggested Saly, who wanted a significant sum for the model and free housing in Copenhagen. The government concluded the contract with Saly in Spring 1752, but because of conflict with ongoing projects Saly did not arrive in Denmark until 8 October 1753, bringing with him his parents, his two sisters, and at least one assistant. Work began on the monument that same year.[7]

Saly showed the king the first sketch of the equestrian statue on 4 December 1754. The king approved a sketch for the whole monument in August 1755, after which Saly began a thorough study of horses from the king’s stalls. This resulted in a small model, which he showed the king in November 1758. Casts of this model are found in both the collection of the Academy and the State Collection, now the Danish National Gallery. After having set up an appropriate studio, Saly carried out the work on the large model of the equestrian statue from 1761 to 1763. The plaster cast was presented to the Academy members on 3 February 1764. The king also saw this model. Preparations for the bronze casting took four more years, and Frenchman Pierre Gors did the casting on 2 March 1768. The year 1768 is officially considered the statue’s completion date.[7]

The statue

The bronze was cast on 2 March 1768 by Frenchman Pierre Gors and weighed some 22 tons.[8] Another three years were spent on finishing the work, which was inaugurated in 1771. Including the base, the statue reaches a height of almost 12 m (39 ft). Saly reported he had been inspired by the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius in Rome as well as by Giambologna's equestrian Henry IV on the Pont Neuf in Paris. But perhaps his greatest inspiration was Edmé Bouchardon's Louis XV (destroyed during the French Revolution) in Place Louis XV, now the Place de la Concorde. It had just been completed when Saly left for Denmark.[9]

Saly first modelled a lifelike portrait of the King. He made a few small bronze castings, the last of which was approved by Frederik V in 1755. Saly then went on to study horses in the royal stables. In 1758, he prepared a model about a meter in height, which the king applauded. Copies still exist in Copenhagen's museums. The King's portrait, where he is depicted as a Roman emperor capped with laurels, has however been lost.[9]

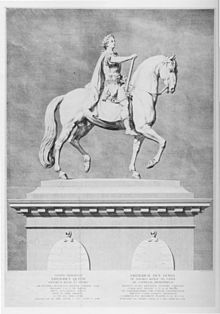

Engraving and medals

Johan Martin Preisler made a large engraving of the equestrian statue (1769) in commemoration of its completion.[10] The Danish Asiatic Company cast two medallions, one by Johan Henrik Wolff[11] and the other by Daniel Jensen Adzer.[12] The base for the statue was delivered first, in 1770, while the unveiling of the statue itself finally took place in the courtyard at Amalienborg Palace on 1 August 1771, five years after the King’s death in 1766. It commands the site still.[7] The statue's base was renovated in 1997–1998.[13]

Danish Culture Canon

In the 21st century, the Danish Culture Canon's committee for the visual arts pointed out that the statue, which took 14 years to complete, cost more than Amalienborg's four palatial buildings which surround it. It was considered to be the jewel of that exquisite environment, an entity which could only be created at the time. It has been preserved unaltered to this day, unlike many similar bronzes, which were melted down for weapons.[14] The painting Amalienborg Square, Copenhagen by Vilhelm Hammershøi places the statue in a central, monumental role.

Gallery

See also

References

- The Edinburgh gazetteer: or Geographical dictionary. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green. 1827. p. 333.

- Doubleday, Nelson; Cooley, C. Earl (1961). Encyclopedia of world travel. Doubleday. p. 117. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- American Architect and Building News: 1890 (Public domain ed.). James R. Osgood & Company. 1890. pp. 167–. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- Sitwell, Sacheverell (1956). Denmark. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-1-4482-0339-0. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- Gaze, Delia (1 July 1997). Dictionary of Women Artists. Taylor & Francis. pp. 348–. ISBN 978-1-884964-21-3. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- Chastel-Rousseau, Charlotte (1 March 2011). Reading the Royal Monument in Eighteenth-Century Europe. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 108, 124–. ISBN 978-0-7546-5575-6. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- Bent Sørensen, "Jacques François Joseph Saly", Kunstindeks Danmark & Weilbacks kunstnerleksikon. (in Danish) Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- Meilby, Mogens (1996). Journalistikkens grundtrin : fra ide til artikel (in Danish). Forlaget Ajour. p. 262. ISBN 978-87-89235-22-6. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- Jens Fleischer, "Amalienborg Slotsplads". (in Danish) Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- "J.M. Preisler", Danske Biografisk Leksikon. (in Danish) Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Galster, Georg (1936). Danske og norske Medailler og Jetons ca. 1533 – ca. 1788 (in Danish). Copenhagen: Selskabet for Udgivelse af danske Mindesmærker. pp. 334–349.

- Ph. Weilbach, "Saly, Jacques François Joseph", Dansk Biografisk Leksikon, (Runeberg) page 582. (in Danish) Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- "Rytterstatuen" Archived 2013-02-25 at the Wayback Machine, Slotte & Kulturegendomme. (in Danish) Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- "Frederik V" Archived December 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Kulturkanonen. (in Danish) Retrieved 20 January 2013.

_MRABASF_02.jpg)