Pericardium

The pericardium, also called pericardial sac, is a double-walled sac containing the heart and the roots of the great vessels. The pericardial sac has two layers, a serous layer and a fibrous layer. It encloses the pericardial cavity which contains pericardial fluid.

| Pericardium | |

|---|---|

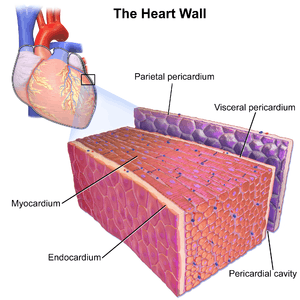

Walls of the heart, showing pericardium at right. | |

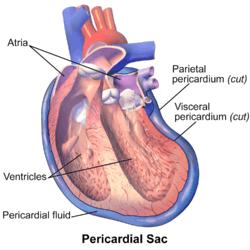

Cutaway illustration of pericardial sac | |

| Details | |

| Location | A sac around the heart |

| Artery | Pericardiacophrenic artery |

| Nerve | Phrenic nerve |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Pericardium |

| Greek | περίκάρδιον |

| MeSH | D010496 |

| TA | A12.1.08.001 A12.1.08.002 A12.1.08.005 |

| FMA | 9869 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The pericardium fixes the heart to the mediastinum, gives protection against infection and provides the lubrication for the heart. It receives its name from Ancient Greek peri (περί; "around") and cardion (κάρδιον; "heart").

Structure

The pericardium is a tough double layered fibroelastic sac which covers the heart.[1] The space between the two layers of serous pericardium (see below), the pericardial cavity, is filled with serous fluid which protects the heart from any kind of external jerk or shock. There are two layers to the pericardial sac: the outermost fibrous pericardium and the inner serous pericardium.

Fibrous pericardium

The fibrous pericardium is the most superficial layer of the pericardium. It is made up of dense and loose connective tissue,[2] which acts to protect the heart, anchoring it to the surrounding walls and preventing it from overfilling with blood. It is continuous with the outer adventitial layer of the neighboring great blood vessels.

Serous pericardium

The serous pericardium, in turn, is divided into two layers, the parietal pericardium, which is fused to and inseparable from the fibrous pericardium, and the visceral pericardium, which is part of, or in some textbooks synonymous with, the epicardium.[3] Both of these layers function in lubricating the heart to prevent friction during heart activity.

The visceral layer extends to the beginning of the great vessels (the large blood vessels serving the heart) becoming one with the parietal layer of the serous pericardium. This happens at two areas: where the aorta and pulmonary trunk leave the heart and where the superior vena cava, inferior vena cava and pulmonary veins enter the heart.[4]

In between the parietal and visceral pericardial layers there is a potential space called the pericardial cavity, which contains a supply of lubricating serous fluid known as the pericardial fluid. Pericardial recesses are small spaces in the pericardial cavity.[5] Pericardial fluid filling these recesses may mimick mediastinal lymphadenopathy.[5]

When the visceral layer of serous pericardium comes into contact with heart (not the great vessels) it is known as the epicardium. The epicardium is the layer immediately outside of the heart muscle proper (the myocardium).[4] The epicardium is largely made of connective tissue and functions as a protective layer. During ventricular contraction, the wave of depolarization moves from the endocardial to the epicardial surface.

Anatomical relationships

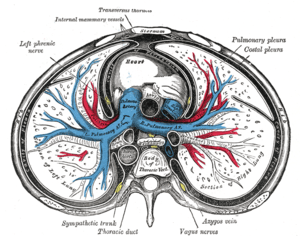

- Surrounds heart and bases of pulmonary artery and aorta.

- Deep to sternum and anterior chest wall.

- The right phrenic nerve passes to the right of the pericardium.

- The left phrenic nerve passes over the pericardium of the left ventricle.

- Pericardial arteries supply blood to the dorsal portion of the pericardium.

Function

- Sets heart in mediastinum and limits its motion

- Protects it from infections coming from other organs

- Prevents excessive dilation of the heart in cases of acute volume overload

- Lubricates the heart

Clinical significance

Inflammation of the pericardium is called pericarditis. This condition typically causes chest pain that spreads to the back that is worsened by lying flat. In patients suffering with pericarditis, a pericardial friction rub can often be heard when listening to the heart with a stethoscope. Pericarditis is often caused by a viral infection (glandular fever, cytomegalovirus, or coxsackievirus), or more rarely with a bacterial infection, but may also occur following a myocardial infarction. Pericarditis is usually a short-lived condition that can be successfully treated with painkillers, anti-inflammatories, and colchicine. In some cases, pericarditis can become a long-term condition causing scarring of the pericardium which restricts the heart's movement, known as constrictive pericarditis. Constrictive pericarditis is sometimes treated by surgically removing the pericardium in a procedure called a pericardiectomy.[6]

Fluid can build up within the pericardial sack, referred to as a pericardial effusion. Pericardial effusions often occur secondary to pericarditis, kidney failure, or tumours and frequently do not cause any symptoms. However, large effusions or effusions that accumulate rapidly can compress the heart in a condition known as cardiac tamponade, causing breathlessness and potentially fatal low blood pressure. Fluid can be removed from the pericardial space for diagnosis or to relieve tamponade using a syringe in a procedure called pericardiocentesis.[7] For cases of recurrent pericardial effusion, an operation to create a hole between the pericardial and pleural spaces can be performed, known as a pericardial fenestration.

The congenital abscence of pericardium is rare. However, if it happens, it is usually occurs on the left side. Those affected usually do not have any symptoms and they are usually discovered incidentally. About 30 to 50 percent of the affected people have other heart abnormalities such as atrial septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, bicuspid aortic valve, and lung abnormalities. On chest X–ray, the heart looks posteriorly rotated. Another feature is the sharp delineation of pulmonary artery and transverse aorta due to lung deposition between these two structures. If there is partial abscence of pericardium, there will be bulge of the left atrial appendage. On CT and MRI scans, similar findings as chest X–ray can be shown. The left sideded partial pericardium defect is difficult to see because even a normal pericardium is difficult to be seen on CT and MRI. A complete pericardial defect will show the heart displaced to the left with part of the lungs squeezed between inferior border of heart and diaphragm.[8]

Additional images

- Fibrous pericardium

See also

References

- Dorland's (2012). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Elsevier Saunders. p. 1412. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- Tortora, Gerard J.; Nielsen, Mark T. (2009). Principles of Human Anatomy (11th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 84–5. ISBN 978-0-471-78931-4.

- Color atlas of fetal and neonatal histology. Ernst, Linda., Ruchelli, Eduardo D., Huff, Dale S. New York: Springer. 2011. pp. 5. ISBN 9781461400196. OCLC 755068872.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Laizzo, P.A. (2009). Handbook of Cardiac Anatomy, Physiology, and Devices (2nd ed.). Humana Press. pp. 125–8. ISBN 978-1-60327-371-8.

- Dixon, Andrew; Hacking, Craig. "Pericardial recesses". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2019-07-08.

- Byrne, John G; Karavas, Alexandros N; Colson, Yolonda L; Bueno, Raphael; Richards, William G; Sugarbaker, David J; Goldhaber, Samuel Z (2002). "Cardiac Decortication (Epicardiectomy) for Occult Constrictive Cardiac Physiology After Left Extrapleural Pneumonectomy". Chest. 122 (6): 2256–9. doi:10.1378/chest.122.6.2256. PMID 12475875.

- Davidson's 2010, pp. 638–639.

- Kligerman, Seth (January 2019). "Imaging of Pericardial Disease". Radiologic Clinics of North America. 57 (1): 179–199. doi:10.1016/j.rcl.2018.09.001.

External links

- Anatomy photo:21:st-1500 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Mediastinum: Pericardium (pericardial sac)"

- thoraxlesson4 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (heartpericardium)

- Atlas image: ht_pericard2 at the University of Michigan Health System - "MRI of chest, lateral view"