Ephebos

Ephebos (ἔφηβος) (often in the plural epheboi), also anglicised as ephebe (plural: ephebes) or archaically ephebus (plural: ephebi), is a Greek term for a male adolescent, or for a social status reserved for that age, in Antiquity.

History

Greece

Though the word can simply refer to the adolescent age of young men of training age, its main use is for the members, exclusively from that age group, of an official institution (ephebeia) that saw to building them into citizens, but especially training them as soldiers, sometimes already sent into the field; the Greek city state (polis) mainly depended, as the Roman republic before Gaius Marius' reform, on its militia of citizens for defense.

In the time of Aristotle the names of the enrolled ephebi were engraved on a bronze pillar (formerly on wooden tablets) in front of the council-chamber. After admission to the college, the ephebus took the oath of allegiance, recorded in histories by Pollux and Stobaeus (but not in Aristotle), in the temple of Aglaurus, and was sent to Munichia or Acte to form one of the garrison. At the end of the first year of training, the ephebi were reviewed, and, if their performance was satisfactory, were provided by the state with a spear and a shield, which, together with the chlamys (cloak) and petasos (broad-brimmed hat), made up their equipment. In their second year they were transferred to other garrisons in Attica, patrolled the frontiers, and on occasion took an active part in war. During these two years they were free from taxation, and were generally not allowed to appear in the law courts as plaintiffs or defendants. The ephebi took part in some of the most important Athenian festivals. Thus during the Eleusinian Mysteries they were sent to fetch the sacred objects from Eleusis and to escort the image of Iacchus on the sacred way. They also performed police duty at the meetings of the ecclesia.[1]

After the end of the 4th century BC, the institution underwent a radical change. Enrolment ceased to be obligatory, lasted only for a year, and the limit of age was dispensed with. Inscriptions attest a continually decreasing number of ephebi, and with the admission of foreigners the college lost its representative national character. This was mainly due to the weakening of the military spirit and the progress of intellectual culture. The military element was no longer all-important, and the ephebia became a sort of university for well-to-do young men of good family, whose social position has been compared with that of the Athenian "knights" of earlier times. The institution lasted till the end of the 3rd century A.D.[1]

In regards to Greek mythology, the ephebe was a young man or initiate, around the ages of 17 to 20, who was put through a period of isolation from his prior community, usually the world of his mother, where he was a child in the community. The ephebe would need to hunt, rely on his senses, on aggression, stealth, and trickery to survive. At the end of the initiation, the ephebe was reincorporated back into society as a man. The idea was that if the community was ever threatened, its men would have these skills needed to protect it.

Rome

In Rome, where the elite (mainly patricians) were often sent to Greece or received Greek teachers, the Greek word was adopted in the Latinate form ephebus (plural ephebi), and fixed at the 16 to 20 age bracket. Several new officials were introduced, one of special importance being the director of the Diogeneion, where youths under age were trained for the ephebia. At this period the college of ephebi was a miniature city; its members called themselves "citizens", and it possessed an archon (ruler), strategos, herald and other officials, after the model of ancient Athens.[1]

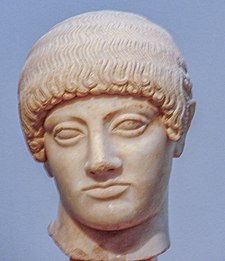

Sculpture

In Ancient Greek sculpture, an ephebe is a sculptural type depicting a nude ephebos (Archaic examples of the type are also often known as the kouros type, or kouroi in the plural). This typological name often occurs in the form "the X Ephebe", where X is the collection to which the object belongs or belonged, or the site on which it was found (e.g. the Agrigento Ephebe).

Sources and references

-

- H. Jeanmaire, Couroi et Courètes: Essai sur l'éducation spartiate et sur les rites d'adolescence dans l'Antiquité hellénique, Bibliothèque universitaire, Lille, 1939

- C. Pélékidis, Éphébie: Histoire de l'éphébie attique, des origines à 31 av. J.-C., éd. de Boccard, Paris, 1962

- O. W. Reinmuth, The Ephebic Inscriptions of the Fourth Century B.C., Leiden Brill, Leyde, 1971

- P. Vidal-Naquet, Le Chasseur noir et l'origine de l'éphébie athénienne, Maspéro, 1981

- P. Vidal-Naquet, Le Chasseur noir. Formes de pensée et formes de société dans le monde grec, Maspéro, 1981

- U. von Wilamowitz-Moellendorf, Aristoteles: Aristoteles und Athen, 2 vol., Berlin, 1916

Further reading

- Budin, Stephanie Lynn (2013). Intimate Lives of the Ancient Greeks. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-31-338572-8.

- Dodd, David; Faraone, Christopher A., eds. (2013). Initiation in Acient Greek Rituals and Narratives: New Critical Perspectives. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13-514365-7.

- Farenga, Vincent (2006). Citizen and Self in Ancient Greece: Individuals Performing Justice and the Law. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-13-945678-4.

- Sage, Michael (2002). Warfare in Ancient Greece: A Sourcebook. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13-476331-3.