Emeryk Hutten-Czapski

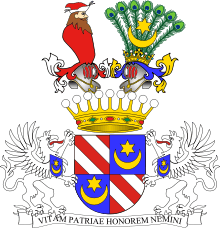

Emeryk Hutten-Czapski, Leliwa coat of arms (October 17, 1828 – July 23, 1896) was a Polish Count, scholar, ardent historical collector and numismatist.[1]

Emeryk Hutten-Czapski | |

|---|---|

Engraving by W.A. Bobrow, 1876 | |

| Born | October 17, 1828 Stańków |

| Died | July 23, 1896 (aged 67) |

| Spouse(s) | Elżbieta Karolina von Meyendorff |

| Children | Zofia, Karol, Jerzy, Elżbieta |

| Parent(s) | Karol Czapski, Fabianna Obuchowiczówna |

Hutten-Czapski was born Emeryk Zachariasz Mikołaj Hutten-Czapski in the town of Stańków near Minsk (then in the Lithuanian part of the partitioned Poland). His parents were Count Karol Hutten-Czapski (1777-1836)[2] and Fabianna Obuchowicz h. Jasieńczyk (1775-1836).[3] He was the grandson of Franciszek Stanisław Kostka Hutten-Czapski (1725-1802), the last voivode of Chełmno during the First Republic, who inherited parts of the Radziwiłł property in Belarus (including Stańków) and in Volhynia and moved there from the former Royal Prussia.[1]

Career

Thanks to his aristocratic background, Emeryk Czapski spoke several languages including Polish, French, German and Russian, and knew Greek and Latin. After studying in St. Petersburg Czapski entered the Russian civil service where he had reached high administrative positions: from Chamberlain of the Court, the Secret State Counsel (1863–1864), Governor of Great Novgorod, the General manager of the Forest Department in the Ministry of the Russian State Property, and finally the Deputy Governor of St. Petersburg in 1865. In 1874, the Tsarist authorities recognized his Count title "Hutten" given to his ancestors (of the Rzewuski family line) 100 years earlier.[1][4]

Hutten-Czapski left the civil service in 1879 and settled into his estate in Stańków. Over the following years he gathered an unsurpassed collection of Russian and Polish coins, medals and orders, banknotes, Russian and Polish engravings, militaria including suits of armour, glasswork, textiles, oil paintings, and old prints. The items were obtained mainly through purchasing the collections of other magnates including Zygmunt Czarnecki, Natalia Kicka, Leon Skórzewski, Kazimierz Stronczyński, Leon Zwoliński, and Władysław Morsztyn.[1][5] In 1885, Emeryk sold his very important collection of some 900 rare Russian coins to Grand Duke George Mikhailovich of Russia (1863–1919), who was one of the great coin collectors of his days.[6] Emeryk used the proceeds to expand his collection of Polish coins.

Contribution to National Museum of Poland

In 1894 Czapski moved, with his vast collections, to the royal city of Kraków in the Austrian Partition, a center of culture and art known frequently as the "Polish Athens" – where Polish was the language of local government.[7] After his untimely death in 1896, his widow donated his collections to the city in 1903 along with the palace he bought in 1894 specifically for that purpose, thus launching the Emeryk Hutten-Czapski Museum in Kraków (located on ul. Pilsudskiego 12).[8][9] It is a division of the National Museum at present. His five-volume work about the Polish coins is still the basic source-material today for Polish coin collecting. In 2016, on the grounds of The Emeryk Hutten-Czapski Museum, the National Museum dedicated a new pavilion to Emeryk's grandson, the painter, Jozef Czapski.[10]

Private life

Count Emeryk Hutten-Czapski was married to Elżbieta Karolina von Meyendorff (1833–1916) and had four children with her: Zofia (1857-1911), Karol Hutten-Czapski (1860–1904, president of Mińsk), Jerzy (1861–1930) and Elżbieta (1867-1877). He was buried in Kraków, at the historic Rakowicki Cemetery in July 1896.[11]

Notes and references

- Bogumiła Haczewska. "Emeryk hrabia Hutten-Czapski (1828-1896). Wielki numizmatyk i kolekcjoner" [Count Emeryk Hutten-Czapski. Great numismatist and collector.] (in Polish). Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Muzeum im. Emeryka Hutten-Czapskiego. Archived from the original on August 28, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- Minakowski, Marek. "Karol Hutten-Czapski h. Leliwa". sejm-wielki.

- Minakowski, Marek. "Fabianna Obuchowicz h. Jasieńczyk". sejm-wielki.

- M.J. Minakowski. "Emeryk Zachariasz hr. Hutten-Czapski h. Leliwa". ID: 3.598.111 (in Polish). Genealogia potomków Sejmu Wielkiego. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- Bogumiła Harczewska, Elżbieta Korczyńska (1997). "Wystawa kolekcji w stulecie śmierci" [Emeryk Hutten Czapski commemorative exhibit for the 100th anniversary of his death] (in Polish). Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- Smirnova, Natalya. "COLLECTIONNEURS CÉLÈBRES (GRAND DUKE GEORGII MIKHAILOVICH )" (PDF). inc-cin. International Numismatic Council.

- Bożena Szara (6 April 2001). "Między dwoma światami czyli powrót do przeszłości" [Between the two worlds, or a return to the past] (in Polish). Przegląd Polski. Archived from the original (Internet Archive) on July 23, 2011. Retrieved October 14, 2012. Search key: "polskie Ateny".

- Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie. "The Hutten-Czapski Museum". mnk. The National Museum of Cracow.

- Editorial board (2015). "Emeryk Hutten-Czapski Museum". About. National Museum in Krakow. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- National Museum of Krakow. "The Jozef Czapski Pavilion". National Museum of Krakow. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- Net-Line (November 21, 2011). "Emeryk hrabia Hutten-Czapski". Gravesite photographs (in Polish). Kraków - Cmentarz Rakowicki (homepage). Retrieved October 14, 2012.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Emeryk Hutten-Czapski Palace in Kraków. |