Elliott Cresson

Elliott Cresson (March 2, 1796 – February 20, 1854) was an American philanthropist who gave money to a number of causes after a brief career in the mercantile business. He established the Elliott Cresson Medal of the Franklin Institute in 1848, and helped found and manage the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, today's Moore College of Art and Design. Cresson was a member of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) and a strong supporter of the Philadelphia branch of the American Colonization Society, a group fighting slavery that relocated former slaves and free African Americans to colonies in Liberia.[1] Cresson was called "the most belligerent Friend the Society ever had."[2]

Elliott Cresson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 2, 1796 Philadelphia |

| Died | February 20, 1854 (aged 57) Philadelphia |

| Occupation | Merchant, philanthropist |

Early career

Cresson was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on March 2, 1796, the first child of John Elliott Cresson and Mary Warder Cresson. The infant Cresson represented the seventh generation of Cressons born in the United States.[1] John Elliott Cresson died in 1814, and Elliott Cresson continued to reside, unmarried, at 730 Sansom Street with his widowed mother until his death.[1]

In 1818, Cresson's uncle Caleb Cresson, Jr. gave him control of the very prosperous mercantile business he had built up. In 1824, Cresson left the business to pursue philanthropic goals.[1]

Liberia

Cresson was interested in the idea of moving freed slaves and African-American citizens to Africa, an idea shared for a few years in the late 1820s by Boston abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison.[1] Cresson felt that ex-slaves, surrounded as they were by white people of greater means, found it too difficult to lift themselves up. His belief was that new circumstances among a primarily black culture would effect a beneficial change in character for the former slaves.[3] Cresson joined the Philadelphia organization known as the Young Men's Colonization Society, a branch of the American Colonization Society, and soon became its strongest, most active member. Beginning in 1830, Cresson saw in the national organization's finances a lack of accountability and rising debts, and he warned them against such fiscal folly.[4]

In 1832–1833, Cresson traveled to England and Liberia to promote the cause. He joined in an effort by the Philadelphia and the New York City auxiliaries to act more independently. The Philadelphia group founded Port Cresson (today Buchanan, Liberia) with the intent that the newly established black settlers would control the Saint John River and thereby stop the flow of some 1200 slaves per month.[5] Cresson traveled to Liberia in early 1833 to help establish the colony,[6] sent on his way by a poem from Lydia Sigourney which finished with:

Sad Afric's hand hath bound thee,

Among her jewels rare;—

Her talisman is round thee,

Her tearful, grateful prayer.

Go forth—God's peace possessing!

To all mankind a friend;—

Full be thy cup of blessing,Where'er thy wanderings tend! [6]

By 1833, Garrison was decrying the efforts of the American Colonization Society, saying it was just a perpetuation of slavery. Cresson worked to stop the damage caused by Garrison's reversal, and wrote Garrison directly on two occasions.[7] In spite of his efforts, Cresson was partly blamed for the withdrawal of some Southern state auxiliaries from the national organization.

The Port Cresson colony was attacked in 1835 by Bassa tribesmen who were incited by Spanish slave traders. All the buildings were destroyed, 20 of 126 colonists were killed, and the rest escaped to the nearby colony of Edina.[1] A month later, a new colony was established at Bassa Cove.[8]

By the efforts of Cresson and his New York counterpart, the American Colonization Society went through a reorganization, with fiscal responsibility first on the list of changes. Cresson traveled the South in the late 1830s to promote colonization of Liberia, and wrote in 1840 that the whole region, particularly Kentucky, seemed ready to send its slaves to Liberia. emancipation of slaves was seen to be wholly contingent upon their removal from the United States. Slaveholders expected compensation for losing workers.[9]

Franklin Institute

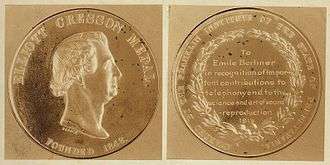

In late 1824, Cresson was nominated and elected to the Franklin Institute, becoming a life member. In 1846, he announced his intention to create a Medal fund.[1] In 1848, Cresson gave $1,000 to establish the Elliott Cresson Medal,[10] a gold medal awarded "for some discovery in the Arts and Sciences, or for the invention or improvement of some useful machine, or for some new process or combination of materials in manufactures, or for ingenuity skill or perfection in workmanship."[1] The medal was first awarded in 1875, to six firms or persons.[1]

Silver medals were proposed by Cresson in 1850, to be awarded in 1851 to the largest producers in the Pennsylvania colonies of Liberia of coffee, sugar, palm oil, and cotton. The Franklin Institute adopted the award, but no such medals were ever given out.[1]

Women's college

In 1850, Sarah Worthington King Peter wrote to the Franklin Institute about her drawing class of some 20 young women becoming a "co-operative, but separate branch" of the Institute.[1] The Franklin Institute established and supervised the Philadelphia School of Design for Women from 1850 to 1853. A group of 17 men were designated the incorporators of the school in 1853. Cresson was among these 17 directors and was elected president at the first meeting.[1] Cresson's enthusiastic work on behalf of the school was cut short by his death. The school flourished and was renamed Moore College of Art and Design in 1989.

Other interests

Cresson wrote to James Madison in 1829 to ask a favor. The ex-president, 79 years old and the last of the Founding Fathers, wrote back to comply with the request for a "sample of my handwriting"[11] and to supply Cresson an autograph each of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.[12]

Cresson subscribed to the Athenaeum of Philadelphia, a special library collection. He bought stock in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Cresson bequeathed to the city of Philadelphia a trust fund designated for planting and renewing shade trees, "excluding such foreign trash as the Lombardy Poplar, Ailanthus, paper Mulberry & similar Exotics."[1]

Legacy

Cresson died at age 58 in Philadelphia on February 20, 1854, of gangrene.[1] He was buried at The Woodlands Cemetery in Philadelphia. The town Cresson, Pennsylvania was named in his honor.[13]

Cresson gave artist Thomas Sully $500 in his will; Sully had painted two portraits of Cresson, one in 1824 and another in 1849. Sully painted a copy of the 1849 portrait one year after Cresson's death. Another beneficiary in Cresson's will was William Bacon Stevens, the rector of St. Andrew's Church in Philadelphia, and the former state historian of Georgia. Others in the will included three sons of Cresson's sister Sara and the Athenaeum of Philadelphia.[1]

The Franklin Institute continued awarding the Elliott Cresson Medal, also known as the Elliott Cresson Gold Medal, for distinguished work in science until 1998 when they reorganized their endowed awards under one umbrella, The Benjamin Franklin Medals.[10] A total of 268 people or groups were given the award during its lifetime.[14]

References

- Notes

- The Franklin Institute. Donors of the Medals and their histories. The Elliott Cresson Medal - Founded in 1848 - Gold Medal Archived 2010-05-28 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on July 13, 2009.

- Fox, 1919, p. 99

- Innes, 1833, p. 230.

- Fox, 1919, p. 103.

- Innes, 1833, p. 142.

- Innes, 1833, p. viii.

- Fox, 1919, pp. 99–100

- WorldStatesmen.org Liberia, Retrieved on July 13, 2009.

- Fox, 1919, p. 188.

- The Franklin Institute. Awards. About the Awards: History and Facts, Retrieved on July 13, 2009.

- Library of Congress. James Madison papers, item mjm 22_0915_0916

James Madison to Elliott Cresson, April 23, 1829. Retrieved on July 13, 2009. - Library of Congress. James Madison papers, item mjm 22_0987_0987

James Madison to Elliott Cresson, June 19, 1829. Retrieved on July 13, 2009. - Cambria County, Pennsylvania. Cresson Archived 2012-07-31 at Archive.today. Retrieved on July 13, 2009.

- The Franklin Institute. Awards. Cresson Medal winners Archived 2009-02-01 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved on July 13, 2009.

- Bibliography

- Fox, Early Lee. The American Colonization Society, 1817-1840, 1919

- Innes, William; Cresson, Elliott. Liberia: Or, The Early History & Signal Preservation of the American Colony of Free Negroes on the Coast of Africa, Waugh & Innes, 1833