Elise Johnson McDougald

Elise Johnson McDougald (October 13, 1885 – June 10, 1971),[3] aka Gertrude Elise McDougald Ayer, was an American educator, writer, activist and first African-American woman principal in New York City public schools.[4] McDougald's essay "The Double Task: The Struggle for Negro Women for Sex and Race Emancipation" was published in the March 1925 issue of Survey Graphic magazine, Harlem: The Mecca of the New Negro.[5] This particular issue, edited by Alain Locke, helped usher in and define what is now known as the Harlem Renaissance. McDougald's contribution to this magazine, which Locke adapted for inclusion as "The Task of Negro Womanhood" in his 1925 anthology The New Negro: An Interpretation,[6] is an early example of African-American feminist writing.

Elise Johnson McDougald | |

|---|---|

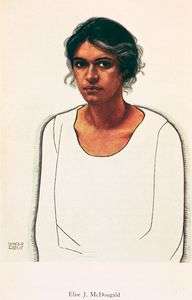

Elise J. McDougald by Winold Reiss [2] | |

| Born | October 13, 1885 |

| Died | June 10, 1971 (aged 85) |

| Occupation | principal |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Girls' Technical School, Hunter College, Columbia University, New York City College |

| Spouses | Cornelius W. McDougald, Vernon A. Ayer |

Biography

Early life

Gertrude Elise Johnson was born in New York City, where her father, Dr. Peter Augustus Johnson, was one of the first African-American doctors and a founder of the National Urban League.[7] Her mother was Mary Elizabeth Whittle, an English woman from the Isle of Wight, and her older brother, Travis James Johnson, was the first African-American graduate of Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1908. He was born in Chichester, England, in 1883,[8] and the family moved to New York in 1884. Elise spent her early days growing up in Manhattan, but also spent summers in New Jersey, as her father's family owned a truck farm there. She would later inherit and manage the farm.[9]

Education

Elise Johnson became the first African-American graduate of the Girls' Technical School in 1903, and was elected president of her senior class. After graduating from high school, she earned a teaching certificate from the New York Training School for Teachers. She never received her bachelor's degree, although she completed coursework at Hunter College, Columbia University and New York City College.[10]

Career

Her teaching career began in 1905 at P.S. 11 in lower Manhattan. She resigned from P.S. 11 in 1911 to focus on her family. In 1916 she went back to work as a vocational counselor at the Manhattan Trade School. She then worked as an industrial secretary at the local branch of the National Urban League, where she started a survey documenting the working conditions of New York City's African-American women. The survey was sponsored not only by the Urban League, but also the Women's Trade Union League and the YWCA. Her New Day for the Colored Woman in Industry in NY City, co-authored with Jessie Clark, was published in 1919.[11] Her work as Executive Secretary for the Trade Union Committee for Organizing Negro Workers brought her into contact with other political organizers such as W.E.B. Du Bois.[12]

In 1935 she was temporarily appointed principal of P.S. 24 during the times of the Depression, where more than 60% of families and neighborhoods were unemployed. Elise was a part of a community forum of interracial prominent New Yorkers who evaluated the conditions of its city and changes that needed to be made. She testified in the hearings and discussed how she wanted to work to gain the trust of parents, enforce a more relaxed atmosphere, and help provide relief for families struggling.[13] This activism helped her become one of the first pioneers to originate the Activity Program, which placed a large emphasis on intercultural curriculum. This program implemented child-centered progressive education in New York City's public elementary schools. The overall idea for this program was to shift the emphasis on the subject matter to the children instead.[13] Some changes to the schools included experiential learning, self-directed projects, interdisciplinary curriculum, and turn classroom experiments into "democratic living".[14] She later transferred after 10 years to P.S. 119.[15] After her retirement in 1954, she remained active, writing a column in the Amsterdam News on Harlem schools, among other things.[16]

Personal life

Elise Johnson married twice. Her first husband was attorney Cornelius W. McDougald; they divorced. She married her second husband, doctor Vernon A. Ayer, in 1928.[17]

She died at her home on June 10, 1971, at the age of 86. She was survived by her second husband and by two children of her first marriage, Dr. Elizabeth McDougald and attorney Cornelius McDougald Jr.[16][18]

References

- "Elise J. McDougald". NYPL Digital Collections. The New York Public Library, Astor, Lennox, and Tilden Foundation. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- "Elise J. McDougald". NYPL Digital Collections. The New York Public Library, Astor, Lennox, and Tilden Foundation. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- Her birthdate is also given as October 11, 1884, as in Jessie Carney Smith, Lean'tin L. Bracks and Jessie Carney Smith (eds), Black Women of the Harlem Renaissance Era, Rowman & Littlefield, 2014, p. 9.

- "Mrs. Gertrude E. Ayer Takes Over Duties as Principal of P. S. 24" New York Age (February 2, 1935): 1. via Newspapers.com

- McDougald, Elise (March 1, 1925). "The Double Task: The Struggle of Negro Women for Sex and Race Emancipation". Survey Graphic (Harlem: The Mecca of the New Negro): 689–691.

- Elise Johnson McDougald on “The Double Task: The Struggle of Negro Women for Sex and Race Emancipation”, History Matters.

- Jessie Carney Smith, "Ayer, Gertrude Elise Johnson McDougald", Lean'tin L. Bracks and Jessie Carney Smith (eds), Black Women of the Harlem Renaissance Era, Rowman & Littlefield, 2014, p. 9.

- Obituary of Travis James Johnson. Crisis Magazine, July 12, 1917.

- Johnson, Lauri (2004). "A Generation of Women Activists: African American Female Educators in Harlem, 1930-1950". The Journal of African American History. 89 (3, "New Directions in African American Women's History"): 229. JSTOR 4134076.

- Johnson (2004). "A Generation of Women Activists". The Journal of African American History. 89 (3): 229, 230. JSTOR 4134076.

- Margaret Busby (ed.), "Elise Johnson McDougald", in Daughters of Africa, Cape, 1992, p. 179.

- Ayer, Gertrude. "Letter from Gertrude Elise J. McDougald to W. E. B. Du Bois, October 14, 1925. W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312)". Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- Carlson, Dennis; C. P. Gause, eds. (2007). Keeping the Promise: Essays on Leadership, Democracy, and Education. Peter Lang. ISBN 9780820481999. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- Johnson (2004). "A Generation of Women Activists". The Journal of African American History. 89 (3): 231–232. JSTOR 4134076.

- "Mrs. Gertrude E. Ayer Tendered Farewell Tea by School Staff at Hotel New Yorker", New York Age (February 3, 1945): 4. via Newspapers.com

- Johnson (2004). "A Generation of Women Activists". The Journal of African American History. 89 (3): 232. JSTOR 4134076.

- "Mrs. Elise McDougald, School Principal, Weds Dr. Vernon A. Ayer" New York Age (September 8, 1928): 1. via Newspapers.com

- "1st Black Woman to Get N. Y. Principal License Dies" Jet Magazine (August 5, 1971): 29.