Elis

Elis /ˈiːlɪs/ or Eleia /ɪˈlaɪ.ə/ (Greek: Ήλιδα, romanized: Ilida, Attic Greek: Ἦλις, romanized: Ēlis /ɛ̂ːlis/; Elean: Ϝᾶλις /wâːlis/, ethnonym: Ϝᾱλείοι[1]) is an ancient district in Greece that corresponds to the modern regional unit of Elis.

Elis Ἦλις | |

|---|---|

Region of Ancient Greece | |

Ruins of the Temple of Zeus, Olympia | |

| Location | Peloponnese |

| Major cities | Elis, Olympia |

| Dialects | Doric |

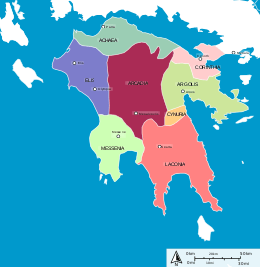

Elis is in southern Greece on the Peloponnese, bounded on the north by Achaea, east by Arcadia, south by Messenia, and west by the Ionian Sea. Over the course of the archaic and classical periods, the polis "city-state" of Elis controlled much of the region of Elis, most probably through unequal treaties with other cities; many inhabitants of Elis were Perioeci—autonomous free non-citizens. Perioeci, unlike other Spartans, could travel freely between cities.[2] Thus the polis of Elis was formed.

The local form of the name was Valis, or Valeia, and its meaning, in all probability was, "the lowland" (compare with the word "valley"). In its physical constitution Elis is similar to Achaea and Arcadia; its mountains are mere offshoots of the Arcadian highlands, and its principal rivers are fed by Arcadian springs.[3]

According to Strabo,[4] the first settlement was created by Oxylus the Aetolian who invaded there and subjugated the residents. The city of Elis underwent synoecism—as Strabo notes—in 471 BC.[5] Elis held authority over the site of Olympia and the Olympic games.

The spirit of the games had influenced the formation of the market: apart from the bouleuterion, the place the boule "citizen's council" met, which was in one of the gymnasia, most of the other buildings were related to the games, including two gymnasia, a palaestra, and the House of the Hellanodikai.

Districts

As described by Strabo,[6] Elis was divided into three districts:

- Koilē (Κοίλη "Hollow", Latinised Coele), or Lowland Elis

- Pīsâtis (Πισᾶτις "[territory] of Pisa")

- Triphylia (Τριφυλία Triphūlía "Country of the Three Tribes").

Koilē Elis, the largest and most northern of the three, was watered by the river Peneus and its tributary, the Ladon. The district was famous during antiquity for its cattle and horses. Pisatis extended south from Koilē Elis to the right bank of the river Alpheios, and was divided into eight departments named after as many towns. Triphylia stretched south from the Alpheios to the river Neda.[3]

Nowadays Elis is a small village of 150 citizens located 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) NE of Amaliada, built over the ruins of the ancient town. It has a museum that contains treasures, discovered in various excavations. It also has one of the most well-preserved ancient theaters in Greece. Built in the fourth century BC, the theater had a capacity of 8,000 people; below it, Early Helladic, sub-Mycenaean and Protogeometric graves have been found.[7][8]

History

Early history

The original inhabitants of Elis were called Caucones and Paroreatae. They are mentioned by Homer[9] for the first time in Greek history under the title of Epeians, as setting out for the Trojan War, and they are described by him as living in a state of constant hostility with their neighbours the Pylians. At the close of the 11th century BC the Dorians invaded the Peloponnese, and Elis fell to the share of Oxylus and the Aetolians.[3]

These people, amalgamating with the Epeians, formed a powerful kingdom in the north of Elis. After this many changes took place in the political distribution of the country, till at length it came to acknowledge only three tribes, each independent of the others. These tribes were the Epeians, Minyae and Eleans. Before the end of the 8th century BC, however, the Eleans had vanquished both their rivals, and established their supremacy over the whole country. Among the other advantages which they thus gained was the right of celebrating the Olympic games, which had formerly been the prerogative of the Pisatans.[3] Olympia was in Elian land, and tradition dates the first games to 776 BC. The Hellanodikai, the judges of the Games, were of Elian origin. The attempts which the Pisatans made to recover their lost privilege, during a period of nearly two hundred years, ended at length in the total destruction of their city by the Eleans. From the time of this event in 572 BC until the Peloponnesian War, the peace of Elis remained undisturbed.[3]

Peloponnesian War and later

In the war, Elis sided at first with Sparta. But Sparta, jealous of the increasing prosperity of its ally, availed itself of the first pretext to pick a quarrel. At the Battle of Mantinea (418 BC), the Eleans fought against the Spartans, who later took vengeance upon them by depriving them of Triphylia and the towns of the Acrorea. The Eleans made no attempt to re-establish their authority over these places until Thebes rose in importance after the Battle of Leuctra (371 BC). However, the Arcadian confederacy come to the assistance of the Triphylians. In 366 BC hostilities broke out between them, and though the Eleans were at first successful, they were soon overpowered; their capital very nearly fell into the hands of the enemy,[3] and the territory of Triphylia was permanently ceded to Arcadia in 369 BC.[10] Unable to make head against their opponents, they applied for assistance to the Spartans, who invaded Arcadia, and forced the Arcadians to recall their troops from Elis. The general result of this war was the restoration of their territory to the Eleans, who were also again invested with the right of holding the Olympic games.[3]

During the Macedonian supremacy in Greece they sided with the victors, but refused to fight against their countrymen. After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC they renounced the Macedonian alliance. At a subsequent period they joined the Aetolian League. When the whole of Greece fell to Rome, the sanctity of Olympia secured for the Eleans a certain amount of indulgence. The games still continued to attract large numbers of strangers, until they were finally ended by Theodosius in 394 AD, two years previous to the utter destruction of the country by the Gothic invasion under Alaric I.[3]

Democracy in Elis

Elis was a traditional ally of Sparta, but the city state joined Argos and Athens in an alliance against Sparta around 420 BC during the Peloponnesian War. This was due to Spartan support for the independence of Lepreum. As punishment following the surrender of Athens, Elis was forced to surrender Triphylia in 399 BC Eric W. Robinson has argued that Elis was a democracy by around 500 BC, on the basis of early inscriptions which suggest that the people (the dāmos) could make and change laws.[11] Robinson further believes that literary sources imply that Elis continued to be democratic until 365, when an oligarchic faction seems to have taken control (Xen. Hell. 7.4.16, 26).[12]:29–31 At some point in the mid-fourth century, democracy may have been restored; at least, we hear that a particularly narrow oligarchy was replaced by a new constitution designed by Phormio of Elis, a student of Plato (Arist. Pol. 1306a12-16; Plut. Mor. 805d, 1126c).

The classical democracy at Elis seems to have functioned mainly through a popular Assembly and a Council, the two main institutions of most poleis. The Council initially had 500 members, but grew to 600 members by the end of the fifth century (Thuc. 5.47.9). There was also a range of public officials such as the demiourgoi who regularly submitted to public audits.[12]:32

Notable Eleans

Athletes

- Coroebus of Elis, the first ancient Olympic gold-medalist

- Troilus of Elis, 4th century BC equestrian

In mythology

- Salmoneus, Aethlius, Pelops mythological kings of Elis

- Endymion

- Sons of Endymion:

- Epeius

- Aetolus

- Paeon

- Augeas, king of Elis related to the Fifth Labour of Heracles

- Amphimachus, king of Elis and leader of Eleans in the Trojan War

- Thalpius, leader of Eleans in the Trojan War

- Oxylus, king of Elis

Intellectuals

- Alexinus (c. 339–265 BC), philosopher

- Hippias of Elis, Greek sophist

- Phaedo of Elis, founder of the Elean School[13]

- Pyrrho, founder of the Pyrrhonist school of philosophy

Eleans as barbarians

Eleans were labelled as the greatest barbarians barbarotatoi by musician Stratonicus of Athens[14]

And when he was once asked by some one who were the wickedest people, he said, "That in Pamphylia, the people of Phaselis were the worst; but that the Sidetae were the worst in the whole world." And when he was asked again, according to the account given by Hegesander, which were the greatest barbarians, the Boeotians or the Thessalians he said, "The Eleans."

In Hesychius (s.v. βαρβαρόφωνοι) and other ancient lexica,[15] Eleans are also listed as barbarophones. Indeed, the North-West Doric dialect of Elis is, after the Aeolic dialects, one of the most difficult for the modern reader of epigraphic texts.[16]

Notes

- Miller, D. Gary (2014). Ancient Greek Dialects and Early Authors: Introduction to the Dialect Mixture in Homer, with Notes on Lyric and Herodotus. De Gruyter. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-61451-295-0.

- Roy, J. “The Perioikoi of Elis.” The Polis as an Urban Centre and as a Political Community. Ed. M.H. Hansen. Acts of the Copenhagen Polis Centre 4. Copenhagen: Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, Historisk-filosofiske Meddelelser 75, 1997. 282-32

-

- Strabo Geographica Book 8.3.30

- Roy, J. (2002). "The Synoikism of Elis". In Nielsen, T. H. (ed.). Even More Studies in the Ancient Greek Polis. Stuttgart: Steiner. pp. 249–264. ISBN 3-515-08102-X.

- Strabo; trans. by H. C. Hamilton & W. Falconer (1856). "Chapter III. GREECE. ELIS.". Geography of Strabo. II. London: Henry G. Bohn. pp. 7–34.

- Koumouzelis, M. (1980). The Early and Middle Helladic Periods in Elis (PhD). Brandeis University. pp. 55–62.

- Eder B. 2001, "Die submykenischen und protogeometrischen Graber von Elis", Athens

- Iliad 2.615

- Oxford Classical Dictionary, third edition. Electronic Edition. Author Oxford University Press Volume title Oxford Classical Dictionary - E Volume 05 Editor Hornblower, Simon and Antony Spawforth Publisher InteLex Corp. Publisher location Charlottesville, Virginia, U.S.A. Published 2002 Print publisher Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press Print publisher location Oxford: United Kingdom; New York, New York, USA Print volume published 1996

- Robinson, Eric W. (1997). The First Democracies: Early Popular Government Outside Athens. Stuttgart: Steiner. pp. 108–111. ISBN 3-515-06951-8.

- Robinson, Eric W. (2011). Democracy Beyond Athens: Popular Government in the Greek Classical Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84331-7.

- Smith, William. Ancient Library Archived 2007-09-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- Athenaeus. Deipnosophistae, VIII 350a.

- Towle, James A. Commentary on Plato: Protagoras, 341c.

- Sophie Minon. Les Inscriptions Éléennes Dialectales (VI-II siècle avant J.-C.). Volume I: Textes. Volume II: Grammaire et Vocabulaire Institutionnel. École Pratique des Hautes Études Sciences historiques et philogiques III. Hautes Études du Monde Gréco-Romain 38. Genève: Librairie Droz S.A., 2007. ISBN 978-2-600-01130-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ancient Elis. |

- Map from the Hellenic Ministry of Culture

- Elis - the city of the Olympic games

- Mait Kõiv, Early History of Elis and Pisa: Invented or Evolving Traditions?