Elegast

Elegast (elf spirit) is the hero and noble robber in the poem Karel ende Elegast, an early Middle Dutch epic poem that has been translated into English as Charlemagne and Elbegast. In the poem, he possibly represents the King of the Elves. He appears as a knight on a black horse, an outcast vassal of Charlemagne living in the forest. The original Dutch poem uses the name Elegast, while translated versions of the poem commonly use the name Elbegast in German and English, or Alegast in the Scandinavian ballad.

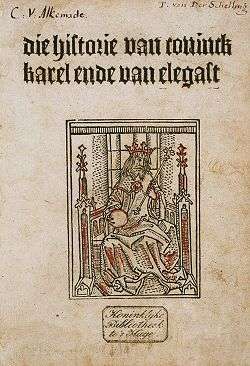

Karel ende Elegast

Karel ende Elegast was an original poem in Middle Dutch that scholars think was probably written at the end of the 12th century, otherwise in the 13th century and set in the region of Charlemagne's castle in Ingelheim. It is a Frankish romance of Charlemagne ("Karel") as an exemplary Christian king who was led on a strange quest to be a robber.[1]

Although the poem does not describe Elegast's background, he was an old friend of Charlemagne that had fallen into disgrace, and his banishment to the forest and his name connotes he was elven. Elegast could put people to sleep magically, could open locks without keys, and has a magic herb that when he puts in his mouth allows him to talk to animals. He lived in the forest, thief to the rich people and kind to poor people.

In summary, Charlemagne has a heavenly vision to go thieving in disguise, so meets with Elegast in the forest at night. Elegast does not recognize the king, as Charlemagne is in disguise as a thief. When Charlemagne suggests they steal from the king's castle, Elegast proves his loyalty to Charlemagne by refusing to steal from the king. Instead, Elegast takes Charlemagne to burglarize the castle of Charlemagne's brother-in-law, Eggeric van Eggermonde. Once they break into the castle, Elegast overhears Eggeric scheming to kill Charlemagne to his wife, who is Charlemagne's sister. In this way Charlemagne learns of a traitor in his court. The next day, when Eggeric arrives in Charlemagne's court, Charlemagne has Eggeric searched and finds his weapons. Elegast duels with Eggeric and exposes him as a traitor. Eggeric is therefore killed, and his wife is given in marriage to Elegast. Elegast's reputation is also restored in the Charlemagne court.

Name

The names Elegast and Alegast and Elbegast, are variants of the same Germanic name, as it were Common Germanic *albi-gastiz, composed of the well attested elements *albi- "elf" and *gastiz "guest".[2]

There is one dwarf named Elbegast in Eddic texts. According to Low German legends, Elbegast was a dwarf who could steal eggs from under birds.[3] In folklore and legends of Northern Europe, Elbegast was called the king of both the elves and dwarves.[4]

Some scholars propose Elegast is the character Alberich, whose name means "king of the elves". Alberich was a sorcerer in Merovingian epics of the 5th to 8th century.

Context

This poetry is unique in the reference to Charlemagne (the "Christian" King) being friends with a character who could be symbolic of an elf or dwarf figure of the forest, as well Charlemagne trying robbery on divine inspiration. In this friendship, the poem combines Frankish legends of Charlemagne with some Dutch-Germanic mythology. The poem is also unique that a Dutch character Elegast is a hero, most other poems of the time concern Frankish people as the hero. Elegast is possibly symbolic of the Dutch people's pre-Christian myth of an ancient elf or folk hero. In the pre-Christian mythology the dwelling in the forest is a religious and sacred dwelling place.

Historically the epic poem may be about a real insurrection against Charlemagne that occurred (circa 785?), as the following event was noted in 1240 in the Chronica Albrici Monachi Trium Fontium:

"By the Austracians a dangerous plot was hatched against Charlemagne, of which Hardericus was the instigator. At the discovery of the plot many were dismembered and many were banished. [ ... ] And, as is told in a song, in order to discover this plot, Charlemagne, urged by an angel, went out thieving at night."[5]

According to legend, Ingelheim (meaning "Angel's Home") was named after the angel that Charlemagne saw in the vision.

Adaptations

Adaptations and translations:

- Dutch: Karel ende Elegast (modern: Karel en Elegast)

- Skandanavian: Alegast Vise (Ballad of Alegast)

- Middle Danish: Krønike by Karl Magnus

- Norse: Karlamagnús saga

- English: Ingelheim: Charlemagne the Robber by Lewis Spencer.

- French epic: Chanson de Basin (a lost manuscript), Vie de Charlemagne

- German: Karlmeinet[6]

- West Frisian: Karel en Elegast (translation by Klaas Bruinsma, 1994).

See also

- Folklore of the Low Countries

- Medieval Dutch literature

References

- Meijer 1971.

- see e.g. Starostin, "Proto-Germanic: *gasti-z".

- Grimm's Teutonic Mythology, 1888, Chapter 17.

- H. A. Guerber, 1895.

- de Ruiter, citing A.M. Duinhoven, Bijdragen tot reconstructie van de Karel ende Elegast. Dl. II. Groningen : Wolters-Noordhoff, 1981:26-27.

- The list of adaptions supplied by de Ruiter.

- Ruiter, Jacqueline de, 'The Guises of Elegast: One story, Differing Genres', in: Carlos Alvar and Juan Perides (eds.), Actes du XVIe Congrès International de la Société Rencesvals, Granada 21-25 juillet 2003, Granada 2005 (prepublication, internet-archive 2007)

- Grimm, Jacob (1835). Deutsche Mythologie (German Mythology); From English released version Grimm's Teutonic Mythology (1888); Available online by Northvegr © 2004-2007, Chapter 17, page 2.

- Guerber, Helene A.Myths of Northern Lands, 1895. File retrieved 2/18/2007.

- Meijer, Reinder. Literature of the Low Countries: A Short History of Dutch Literature in the Netherlands and Belgium. New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1971.

- Spence, Lewis. Ingelheim: Charlemagne the Robber - Retold in English version in Hero Tales and Legends of the Rhine, 1915.

- Germanic etymology database, by S. Starostin. (Proto-Germanic derivatives of: *gasti-z.) File retrieved 5/24/07.

External links

- Karel ende Elegast - Full text in Middle Dutch.

- Ingelheim: Charlemagne the Robber - narrative adaptation in English.

- Karel ende Elegast From the Collections at the Library of Congress