El Paso and Northeastern Railway

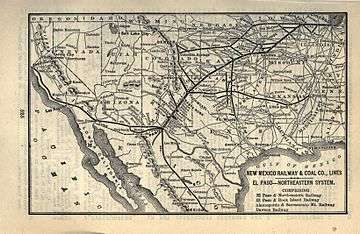

The El Paso and Northeastern Railway (EP&NE) was a short line railroad that was built around the beginning of the twentieth century to help connect the industrial and commercial center at El Paso, Texas, with physical resources and the United States' national transportation hub in Chicago. Founded by Charles Eddy, the EP&NE was the primary railroad in a system organized under the New Mexico Railway and Coal Company (NMRy&CCo), a holding company which owned several other railroads and also owned mining and industrial properties served by the lines.

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Alamogordo, New Mexico |

| Locale | Territory of New Mexico, Texas |

| Dates of operation | 1897–1905 |

| Predecessor | Kansas City, El Paso and Mexico Railroad |

| Successor | El Paso and Southwestern Railroad |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 163 mi (262 km) |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Locale | Territory of New Mexico |

| Dates of operation | 1900–1905 |

| Successor | El Paso and Southwestern Railroad |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 128 mi (206 km) |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Locale | Territory of New Mexico |

| Dates of operation | 1902–1905 |

| Successor | El Paso and Southwestern Railroad |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 132 mi (212 km) |

The EP&NE first connected El Paso with Alamogordo, New Mexico, in 1897, further extensions allowed for tourist excursions to the Sacramento Mountains and some timber extraction. A link with the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad (CRI&P) allowed for the introduction of the Golden State Limited in 1902. When a line connecting to lucrative coalfields was secured, the holding company and its system were folded into the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad, an affiliate of the predecessor of the Phelps Dodge Corporation. The lines of the NMRy&CCo were responsible for the founding of several settlements in the Territory of New Mexico (later New Mexico).

History

The railroad's beginnings lie in the discovery of gold at White Oaks, New Mexico in 1879, at which point railroads began to gain interest in the Tularosa Basin and Sacramento Mountains. The coal deposits in the area were also enticing as they were perceived to be a good source of fuel for the city of El Paso 160 mi (260 km) to the south.[1] An interested railroad promoter, Morris Locke, noted that the forests of the Sacramento Mountains would be a good source of timber.[2] Over the next fifteen years several railroads were projected to link the two settlements but only limited construction had been pursued by the time Charles Eddy developed an interest in linking El Paso with the CRI&P.[1] Eddy kept his interests somewhat quiet and El Pasoans hopefully speculated that the CRI&P might build its own line to El Paso.[3]

El Paso–Alamogordo

The first serious attempt to build a railroad north from El Paso and into the Tularosa Basin came in 1885 when the El Paso, St. Louis and Chicago Railway and Telegraph Company prepared a 5-mile (8.0 km) long roadbed.[4] In 1888 CRI&P engineers began an eastward survey from Liberal, Kansas that projected never built lines through the Maxwell Land Grant to Taos, New Mexico and further west.[5] Meanwhile, some of the partially prepared right-of-way in El Paso was incorporated three years later into the promising Kansas City, El Paso and Mexico Railroad (KCEP&M, led by Morris Locke[2]) which built 10 miles (16 km) of track and graded a further 21 before its debt caught up to it. Construction began in September 1888 with loans from local entrepreneurs and some word of financial commitment from interests in the American Northeast. Just a few days after the first excursion trains operated on the new line, lawsuits were filed in court seeking restitution for the Texas and Pacific Railway, the unpaid shipper of the KCEP&M's construction materials. Although the founders continued to solicit funding, in 1892 the Texas and Pacific purchased the stalled KCEP&M. The new owners did not resume construction.[4]

Eddy had been in contact with the leadership of the CRI&P but had been unsuccessful in his pitch to connect their railroad to El Paso. Eddy had gained an interest in the prospective region after working on engineering projects in southeastern New Mexico. In the Spring of 1897 he led potential investors from Pennsylvania on a camping trip in the Tularosa Basin. Eddy received financial backing from these men but he did immediately not make any major announcements, file for incorporation in the territory or apply for the El Paso–White Oaks railway franchise.[6] In May 1897 on the other side of the country in New Jersey the New Mexico Railway and Coal Company was incorporated, it would become the holding company for Eddy and his group's vertically integrated interests.[2] When another group of men sought the necessary franchise from the El Paso city council, Eddy intervened and won the franchise because of the rival group's inability to pay a performance bond.[6] A few days later (on October 22, 1897[7]) the El Paso and Northeastern Railroad was incorporated in both New Mexico and Texas. By November 1897 the railroad's first line's route had been determined and orders for supplies were being placed.[6]

Using part of the KCEP&M's grade, which Eddy had purchased in full, the EP&NE completed an 85-mile (137 km) line north to a ranch owned by Eddy, where a town was being platted in anticipation of the railroad.[8] The town was named Alamogordo after a location Eddy was familiar with in the Pecos River Valley.[9] It would become the main New Mexican town on the EP&NE in only a matter of a few years.[10] Alamogordo remained the operational base of the EP&NE system for much of its history.[8]

Expansion and affiliated lines

Not long after connecting Alamogordo to El Paso, Eddy, his chief engineer Horace Sumner and their crews set about building the Alamogordo and Sacramento Mountain Railway (A&SM).[11] Described as an "engineering marvel",[10] 28 mi (45 km) were completed by 1898. By 1903 the line climbed 4,747 feet (1,447 m) over 32 mi (51 km) crossing several large trestles and a switchback with ruling grades of 6.4 %. From the outside world it provided improved connections to rich timber country, and later the resort at Cloudcroft—in addition to small communities like La Luz and Russia.[12] The logs harvested in the mountains provided the Alamogordo Lumber Company (owned by the NMRy&CCo) with many of the raw materials necessary to make the ties, poles and structures for the EP&NE's northward expansion.[13]

While work to the east was also under way the EP&NE under its own name was extended further north to Carrizozo, near White Oaks. In 1899 the EP&NE opened a 21 mi (34 km) extension from Carrizozo to Capitan.[14] With an operational railroad in place extending north-by-northeast from El Paso, Eddy was able to better gain the attentions of the CRI&P leadership.[15] It was agreed in December 1900 that Eddy's railroad was to meet the CRI&P in Santa Rosa, New Mexico.[5] The El Paso and Rock Island Railway (EP&RI) was incorporated in 1900 by Eddy to build the remaining 128 mi (206 km) between Santa Rosa and Carrizozo.[15] A tightly-controlled multinational workforce was brought in to expedite construction of the line.[16] This effort was completed on February 1, 1902 when the EP&RI met the CRI&P, operating under the name Chicago, Rock Island and El Paso Railway while in New Mexico.[17] It marked the opening of a new transcontinental route[18] that gave the CRI&P "the shortest line from Chicago and Kansas City to El Paso and Mexico, and by way of the Southern Pacific to Los Angeles."[10]

The coal deposits near White Oaks proved to be a disappointment.[2] Eddy was still determined to link his railroad system to a mineral rich area so he hedged, on the advice of his trusted attorney William Ashton Hawkins, that the outcome of litigation about the ownership of part of the Maxwell Land Grant in northeastern New Mexico would favor the current tenant, an elderly rancher named John Dawson, and Hawkins secured the eventual purchase of a parcel of the contested land grant from him.[19] The approximately 20,000-acre (81 km2; 31 sq mi) parcel was rich in bituminous coal, and Eddy co-founded the Dawson Fuel Company in 1901 to buy and mine the parcel.[20] Work on the Dawson Railway began at a crossing of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway (AT&SF) at French (near present-day Springer).[21] A second construction gang worked north from Tucumcari.[2] The first section of the Dawson Railway opened in November 1902 and linked the interchange with the AT&SF's transcontinental line to the coal mines, sawmills and coke ovens being built near the future townsite of Dawson, New Mexico. Construction of the southern section of the Dawson Railway, from a bridge over the AT&SF line to a junction at Six Shooter Siding (later Tucumcari, located 60 mi (97 km) east-by-northeast of Santa Rosa) with the CRI&P was held up due to litigation with the owners of the Pablo Montoya Grant over the proposed right-of-way. The outcome of those proceedings allowed for the completion of the originally projected 132-mile (212 km) Dawson Railway in 1903.[21]

Sale to the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad and Phelps Dodge

James Douglas, a representative and co-owner of the growing Phelps Dodge mining corporation who was also the owner of the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad (EP&SW), entered negotiations with Eddy over the sale of the NMRy&CCo, the holding company for Eddy's rail and coal properties in the territory and Texas.[22] Eddy was able to convince Phelps Dodge that Dawson coal was better for coking than the coal Phelps Dodge was interested in extracting from northwestern New Mexico so on July 1, 1905 Eddy's properties were transferred to Phelps Dodge, the rail line from El Paso to Dawson becoming the Eastern Division of the EP&SW.[23][2][24]:309, 312[25]:134–135 The A&SM continued to operate for some time as a subsidiary of the EP&SW.[26]:132, 134

Infrastructure, operations and services

Trips to the cool mountain resort of Cloudcroft (elevation 8,650 ft or 2,640 m) were a favorite retreat for El Pasoans around the turn of the century.[26]:134–135 Since the line's opening, Summer excursion trains were operated into the Sacramento Mountains east of Alamogordo via the A&SM from El Paso, and under new ownership as late as 1930.[27] The EP&SW continued to encourage tourism on the A&SM line describing Cloudcroft as the "Roof Garden of the Sky" or "Nature's Roof Garden" and building its own hotel, the Lodge.[26]:134–135 The A&SM itself became a tourist attraction.[28] The same features that gave the line into the Sacramento Mountains its scenic virtue and tourist draw also made it expensive to build, operate and maintain; by necessity and design hauling timber was the primary activity on the line.[2]

The Alamogordo Lumber Company was NMRy&CCo's logging enterprise and owned the logging railways, short spurs and branches, that first harvested the territory's trust land in the Sacramento Mountains. The logging lines were temporary constructions, sometimes little more than tracks laid in the dirt, and initially relied on animal labor. The A&SM carried the lumber company's logs to its sawmill in Alamogordo for processing. While the best consumers for the mill's output were the NMRy&CCo's interests, lumber was also shipped out on the EP&NE destined for other markets, especially the mining districts at Bisbee and Morenci, Arizona. Over the course of one month in 1901 the A&SM handled 850 log cars.[29] Traffic on the A&SM line was not restricted to passengers and logs, a wide variety of other cargo was hauled including express, goods, machinery, produce, and livestock. Two daily roundtrips, one a mixed train, were common, though this frequency could increase more than twofold on Summer weekends.[2]

Passenger traffic on the Cloudcroft branch ceased in March 1937, having been overtaken by automobiles on improved highways. By late 1944, freight traffic had dwindled to a single round trip weekly, also due to highway traffic. All service was discontinued in the autumn of 1947, and the tracks taken up.[30] Some of the large trestles remain, still maintained as historic structures.

The railroad founders were also eager to found a major town that would persist after the railroad was completed; they formed the Alamogordo Improvement Company to develop the area,[31] making Alamogordo an early example of a planned community. The Alamogordo Improvement Company owned all the land, platted the streets, built the first houses and commercial buildings, donated land for a college, and placed a restrictive covenant on each deed prohibiting the manufacture, distribution, or sale of intoxicating liquor.[32] Through Eddy's Dawson Fuel Company, the NMRy&CCo helped spur the early development of Dawson, which is now deserted, in the form of one-hundred dwellings for its workers, in addition to industrial facilities.[20]

The premier long distance train service on the joint EP&NE system was the Winter only Golden State Limited. Year round passenger service was provided by the westbound Chicago and Mexico Express and the eastbound Chicago Express.[33] All of these Chicago–Los Angeles trains used the EP&NE system as an intermediate link between the CRI&P at Santa Rosa and the Southern Pacific Railroad in El Paso.[34] Following the sale of the NMRy&CCo, the EP&SW obtained a lease of the Santa Rosa–Tucumcari section of the El Paso–Chicago route (called the 'Golden State Route') to avoid unsatisfactory interline service with the Rock Island system on the Eastern Division between Dawson and El Paso.[35] Another operational hurdle of the original EP&NE was also solved after the sale; Hawkins was able to secure legal rights to cleaner water from the mountains. Previously the system had relied on alkali and gypsum rich well water that damaged the steam engines' boilers and necessitated frequent repairs.[36]

Footnotes

- Myrick (1990), p. 71, 73–74.

- Glover (1984), Historical Overview.

- Myrick (1990), p. 141–142.

- Myrick (1990), p. 71–73.

- Myrick (1990), p. 142.

- Myrick (1990), p. 73–76.

- "El Paso and Northeastern Railway" (PDF). The New York Times. 23 October 1897. p. 11. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- Myrick (1990), p. 77.

- Townsend & McDonald (1999), p. x-1.

- Anderson (1907).

- Myrick (1990), p. 78.

- Myrick (1990), p. 78–79.

- Myrick (1990), p. 79, 81.

- Myrick (1990), p. 84.

- Myrick (1990), p. 85–86.

- Myrick (1990), p. 87.

- Myrick (1990), p. 145.

- Myrick (1990), p. 91.

- Myrick (1990), p. 84–85.

- Weiser, Kathy (September 2008). "The Ghosts of Dawson". New Mexico Legends. www.Legends of America.com. p. 1. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- Myrick (1990), p. 91–92 & 108.

- Myrick (1990), p. 95–96.

- Myrick (1990), p. 95–96, 98 & 100.

- Keleher, William Aloysius (1982). The Fabulous Frontier : twelve New Mexico items (reprint ed.). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-0621-0. OCLC 8195438.

- Riskin, Marci L (2005). The Train Stops Here: New Mexico's railway legacy. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-3306-3. OCLC 57143199.

- staff (July 1910). "El Paso - the gateway to Mexico". Overland Monthly. San Francisco: Samuel Carson. 56 (1). OCLC 4894800. Retrieved 2-7-10. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - Myrick (1990), p. 81.

- Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, Engineering News (November 1902). Cease, D.L. (ed.). "Railway Engineering in the Southwest". Railroad Trainmens' Journal. Cleveland: Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen. 19 (11): 841–844. OCLC 2970610. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- Glover (1984), The Logging Companies.

- "SP Abandons Cloudcroft Branch," Trains magazine, February 1948

- Townsend & McDonald (1999), p. 5.

- Townsend & McDonald (1999), p. 1, 9, 13 & 44.

- Myrick (1990), p. 147.

- Rock Island Company (1903). The Golden State, a Gratuitous Guide, California. Chicago: Rogers and Co. p. 14. OCLC 38721481.

Golden State Limited.

- Myrick (1990), p. 96.

- Myrick (1990), p. 95 & 100.

References

- Anderson, George B. (1907). History of New Mexico: its resources and people. Los Angeles: Pacific States Publishing Co. pp. 901. OCLC 1692911.

el paso and northeastern railroad.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Glover, Vernon J (September 1984). Logging Railroads of the Lincoln National Forest, New Mexico. Cultural Resources Management. Report no. 4 (online ed.). USDA Forest Service Southwestern Region. Retrieved 9 February 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Myrick, David F. (1990). New Mexico's Railroads: A Historical Survey (revised ed.). Albuquerque, NM.: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-1185-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Townsend, David; McDonald, Clif (July 1999). Centennial: Where the Old West Meets the New Frontier. Alamogordo, NM.: Alamogordo/Otero County Centennial Celebration. ISBN 978-1-887045-05-6. OCLC 41400788.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Cloud-Climbing Railroad: Highest Point on the Southern Pacific - Dorothy Jensen Neal, El Paso: Texas Western Press (1998)

- Captive Mountain Waters; a Story of Pipelines and People - Dorothy Jensen Neal, El Paso: Texas Western Press (1961)