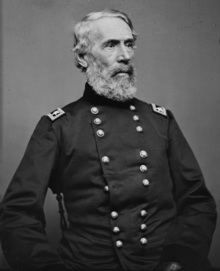

Edwin Vose Sumner

Edwin Vose Sumner (January 30, 1797 – March 21, 1863) was a career United States Army officer who became a Union Army general and the oldest field commander of any Army Corps on either side during the American Civil War.[1] His nicknames "Bull" or "Bull Head" came both from his great booming voice and a legend that a musket ball once bounced off his head.

Edwin Vose Sumner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | Bull, Bull Head |

| Born | January 30, 1797 Boston, Massachusetts |

| Died | March 21, 1863 (aged 66) Syracuse, New York |

| Place of burial | Oakwood Cemetery, Syracuse, New York |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Service/ | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1819–1863 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | 1st U.S. Cavalry Department of the Pacific II Corps, Army of the Potomac |

| Battles/wars | Black Hawk War Mexican–American War Indian Wars Bleeding Kansas American Civil War

|

| Spouse(s) | Hannah W. Foster |

| Children | 6, including Edwin Jr. and Samuel |

Sumner fought in the Black Hawk War, with distinction in the Mexican–American War, on the Western frontier, and in the Eastern Theater for the first half of the Civil War. He led the II Corps of the Army of the Potomac through the Peninsula Campaign, the Seven Days Battles, and the Maryland Campaign, and the Right Grand Division of the Army during the Battle of Fredericksburg. He died in March 1863 while awaiting transfer.

Early life and career

Sumner was born in Boston, Massachusetts, to Elisha Sumner and Nancy Vose Sumner. His early schooling was in Milton Academy in Milton, Massachusetts.[2] He was a first cousin once removed of Charles Sumner, the abolitionist, and a distant cousin of the statesman, Increase Sumner, and his son, the historian William H. Sumner.

In 1819, after losing interest in a mercantile career in Troy, New York, he entered the United States Army as a second lieutenant in the 2nd US Infantry Regiment on March 3, 1819. He was promoted to first lieutenant on January 25, 1825.

Sumner's military appointment was facilitated by Samuel Appleton Storrow, Judge Advocate Major on the staff of General Jacob Jennings Brown of the Northern department. (Storrow had previously served as a mentor to Sumner in Boston.) In recognition of their long-standing friendship, Sumner would later name one of his sons Samuel Storrow Sumner.[3]

He married Hannah Wickersham Foster (1804–1880) on March 31, 1822. They had six children together: Nancy, Margaret Foster, Sarah Montgomery, Mary Heron, Edwin Vose Jr., and Samuel Storrow Sumner. His son Samuel was a general during the Spanish–American War, Boxer Rebellion, and the Philippine–American War. Sumner's daughter, Mary Heron, married General Armistead L. Long in 1860.

Sumner later served in the Black Hawk War and in various Indian campaigns.[4] On March 4, 1833, he was promoted to the rank of captain and assigned to command B Company, the U.S. Dragoon Regiment (later First US Dragoons), immediately upon its creation by Congress.

In 1838, he commanded the cavalry instructional establishment at Carlisle Barracks in Pennsylvania.[4] He was assigned to Ft. Atkinson, Iowa Territory, from 1842 until 1845. He was the fort's commander during most of that period. He was promoted to major of the 2nd Dragoons on June 30, 1846. During the Mexican–American War, Sumner was brevetted for bravery at the Battle of Cerro Gordo (to lieutenant colonel). It was here that he gained the nickname "Bull Head" because of a story about a musket ball that bounced off his head during the battle. At the Molino del Rey he received the brevet rank of colonel. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel of the 1st US Dragoons on July 23, 1848. He served as the military governor of the New Mexico Territory from 1851–53 and was promoted to colonel of the 1st U.S. Cavalry on March 3, 1855.

In 1856 Sumner commanded Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and became involved in the crisis known as Bleeding Kansas. In 1857, as commander of the 1st Cavalry Regiment (1855), he led a punitive expedition against the Cheyenne,[5] and in 1858 he commanded the Department of the West. On January 7, 1861, Sumner wrote to President-elect Abraham Lincoln, advising him to carry a weapon at all times. Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott assigned Sumner as the senior officer to accompany Lincoln from Springfield, Illinois, to Washington, D.C., in March 1861.[6]

Civil War

In February 1861, Brig. Gen. David E. Twiggs was dismissed from the Army for treason by outgoing U.S. President James Buchanan, and on May 12, 1861, Sumner was nominated by the newly inaugurated Lincoln to replace Twiggs as one of only three brigadier generals in the regular army, with date of rank March 16.[7] Sumner was thus the first new Union general created by the secession crisis. He was then sent to replace Brig. Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston, then in command of the Department of the Pacific in California, and thus took no part in the 1861 campaigns of the war.[8] When Sumner left for California, his son-in-law Armistead Lindsay Long resigned his commission and enlisted with the Confederate Army eventually becoming Robert E. Lee's military secretary and an artillery brigadier general.

In November 1861, Sumner was brought back east to command a division.[9] When Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan began organizing the Army of the Potomac in March, Sumner was given command of one of its new corps. McClellan had not originally formed corps within the Army; Sumner was selected as one of four corps commanders by President Lincoln, based on his seniority. The II Corps, commanded during the war by Sumner, Darius N. Couch, Winfield Scott Hancock, and Andrew A. Humphreys, had the deserved reputation of being one of the best in the Eastern Theater. Sumner, who was the oldest of the generals in the Army of the Potomac, led his corps throughout the Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days Battles.[8]

McClellan originally formed a poor opinion of Sumner during the Battle of Williamsburg on May 5, 1862. During McClellan's absence, Sumner directed the inconclusive battle, which failed to impede the Confederate withdrawal up the Peninsula, and McClellan wrote to his wife, "Sumner had proved that he was even a greater fool than I had supposed & had come within an ace of having us defeated."[10] At the Battle of Seven Pines, however, Sumner's initiative in sending reinforcing troops across the dangerously rain-swollen Chickahominy River prevented a Union disaster. He received the brevet of major general in the regular army for his gallantry at Seven Pines. Sumner was struck in the arm and hand by spent balls at the Battle of Glendale. Despite his old-fashioned ideas on discipline and respect for commanding officers, the II Corps troops generally had a positive opinion of him. Sumner was promoted to major general of volunteers on July 4, 1862, with the rank dated to May 5.

In the fall of 1862, at the Battle of Antietam, Sumner was the center of controversy for ordering Brig. Gen. John Sedgwick's division to launch an attack into the West Woods on the morning of the battle. The assault was devastated by a Confederate counterattack, and Sedgwick's men retreated in great disorder to their starting point with over 2,200 casualties. Sumner has been condemned by most historians for his "reckless" attack, his lack of coordination with the other corps commanders, accompanying Sedgwick's division personally and losing control of his other attacking division, failing to perform adequate reconnaissance prior to launching his attack, and selecting an unusual line of battle formation that was so effectively flanked by the Confederate counterattack. Historian M. V. Armstrong's recent scholarship, however, has determined that Sumner did perform appropriate reconnaissance and his decision to attack where he did was justified by the information available to him.[11]

Sumner's other divisions drove the weak Confederate center back, but Sumner was badly shaken by the disaster to Sedgwick and heavy casualties to other Union forces. Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin wanted to attack with his fresh VI Corps, but Sumner, who was senior to him, ordered him to hold back. McClellan sustained Sumner.

Shortly before being fired from command of the army in October, McClellan wrote to the War Department a letter recommending that Sumner be relieved of duty, as he doubted that his age and health would permit him to survive another campaign, but nothing came of this and when Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside succeeded to the command of the Army of the Potomac, he grouped the corps in "grand divisions" and appointed Sumner to command the Right Grand Division. In this capacity, he took part in the disastrous Battle of Fredericksburg, in which the II Corps, now commanded by Major General Darius N. Couch, suffered heavy casualties in frontal assaults against Confederate troops fortified at Marye's Heights.[4]

Transfer and Death

Soon afterward, on Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker's appointment to command the Army of the Potomac on January 26, 1863, Sumner was relieved of his command at his own request,[4] apparently disillusioned with the quarreling in the army and also thoroughly exhausted. He was then reassigned to a new command in the Department of the Ohio, effective in the spring.[12] Before that, Sumner went to his daughter's home in Syracuse, New York, to rest, where he fell ill with fever. He died on March 21, 1863 and was buried in Syracuse's Oakwood Cemetery.

His two sons, Brigadier General Edwin Vose Sumner, Jr. and Major General Samuel S. Sumner, both served in the Civil War and the Spanish–American War.

Grave

Sumner is buried in Section 8, Lot 1 of Oakwood Cemetery in Syracuse. Part of the Teall family plot, the gravesite has some structural problems and issues of disrepair. The Onondaga County Civil War Round Table was raising funds to repair the grave and the general area.

Notes

- Warner 1964, p. 489.

- Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- The Sumner–Storrow relationship is discussed in unpublished 19th-century correspondence of the Storrow family (copies of which are held by descendants). The Storrow–Brown relationship is described in Morris.

-

- Bertbrong, pp. 133–40; Grinnell, pp. 111–21.

- Dupuy 1992, p. 719.

- Eicher 2001, pp. 716–17. The two other line-officer brigadier generals in the regular army as of May 1861 were John Wool and William S. Harney; Joseph E. Johnston, Quartermaster General of the Army, resigned on April 22 to join the Confederate States Army.

- Chisholm 1911.

- Eicher 2001, p. 519.

- Armstrong 2002, p. xvi.

- Armstrong 2002, pp. 39–55.

- Hitchcock, Frederick L., 132nd Pennsylvania, "War from the Inside." 1904, Chapter XI

References

- Armstrong, Marion V. (2002). Disaster in the West Woods: General Edwin V. Sumner and the II Corps at Antietam. Sharpsburg, MD: Western Maryland Interpretive Association. ASIN B0014SER8S.

- Bertbrong, Donald J. The Southern Cheyenne. The civilization of the American Indian series. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1979. OCLC 254915143.

- Dupuy, Trevor (1992). The Harper encyclopedia of military biography. New York, NY: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-270015-5. OCLC 25026255.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eicher, John (2001). Civil War high commands. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3. OCLC 45917117.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grinnell, George Bird. The Fighting Cheyenne. The civilization of the American Indian series. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1956. ISBN 978-0-8061-0347-1. First published 1915 by Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Morris, John D. Sword of the Border: Major General Jacob Jennings Brown, 1775–1828. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-87338-659-0.

- Warner, Ezra (1964). Generals in blue : lives of the Union commanders. Baton Rouge, La: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-0822-7. OCLC 445056.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- U.S. Army Combined Arms Research Library biographies at the Wayback Machine (archived August 8, 2007)

- Territorial Kansas Online biographical sketch

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edwin Vose Sumner. |

- Edwin Vose Sumner biography and timeline

- "Edwin Vose Sumner". Find a Grave. Retrieved February 12, 2008. (portraits, grave, and biography)

- "Sumner, Edwin Vose". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- . . 1914.

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

Documents at the Library of Congress

- Letter from Sumner to Abraham Lincoln, December 17, 1860, stating that he has permission to accompany Lincoln on his trip to Washington.

- Letter from Sumner to John G. Nicolay, January 20, 1861, stating that he will accompany Lincoln on his journey to Washington.

- Letter from Sumner to Abraham Lincoln, January 20, 1861, recommending Judge Edward Bates for Secretary of War.

- Letter from David Davis to Abraham Lincoln, March 6, 1861, recommending that Colonel Sumner be promoted.

- Telegram From Sumner to wife, December 11, 1862, reporting the capture of Fredericksburg.

- Letter from Sumner to Abraham Lincoln, January 10, 1863, seeking appointment to West Point for his grandson.

- Resolution honoring General Edwin Sumner, from the New York Legislature to Abraham Lincoln, March 23, 1863.

- Senate bill to increase the pension of Mrs. Hannah W. Sumner, March 11, 1872

- Senate bill to increase the pension of Mrs. Hannah W. Sumner, April 25, 1872

| Preceded by none |

Commander of the II Corps March 13, 1862 – October 7, 1862 |

Succeeded by Darius N. Couch |