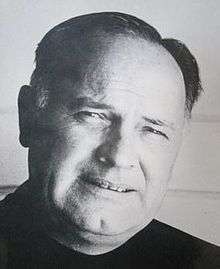

Edward O'Brien (mural artist)

Edward O'Brien was an American artist and muralist.

Early years

Edward O'Brien was born August 11, 1910 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His parents were Irish Catholic. His father was a grocer. O'Brien began going to art galleries and museums at an early age with his grandfather (his father's father). When his grandfather died before he was ten, Edward O'Brien continued to explore art and to draw. At nine, he studied art at the Diocesan Preparatory School. As a teenager, he continued his studies at Carnegie Tech in Pittsburgh, giving up his thoughts of joining the priesthood. By 1931, O'Brien was studying at the Art Institute in Chicago where he met John Rheinhardt, professor of English and Latin at Crane College, who would become his lifelong friend and counsellor.[1]

In the 1930s, Edward O'Brien found work painting murals on public buildings. He also worked as a book illustrator and stained glass designer.

With the arrival of World War Two, O'Brien was rejected from all branches of the armed forces because of a pierced eardrum and back injury. Instead, he took a war industry job and continued his drawing and studying at night.

After the war, Edward O'Brien began a period of drifting. His parents had died and his family rejected him for not going into the priesthood, unlike his younger brother. O'Brien roamed the Midwest in search of work and finally returned to Pittsburgh.[2]

Middle years

In Pittsburgh, Edward O'Brien began a collaboration with sculptor Clarence Courtney and architect Brandon Smith. At this time, he painted his first large mural, together with portraits and religious egg tempura works. In the following years, work took him to Western Pennsylvania and Miami Beach. Work was abundant, but O'Brien felt called to enter a Trappist monastery in Kentucky where he remained in reflection for some time.[3]

At the monastery, Edward O'Brien was inspired by writings of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux. Thereafter, he left to work as a therapist's assistant at a home for handicapped children in Pittsburgh. He also continued his studies and painting.

In 1959, Edward O'Brien went to Mexico City to study the works of the great muralists there. He was especially influenced by Diego Rivera. During his study of Mexican murals, O'Brien took a guided tour to view Our Lady of Guadalupe on the cloak of Juan Diego at the Basilica of Guadalupe. At the Basilica, Edward O'Brien made a profound connection with Our Lady, a connection that would affect the rest of his life's work.[4]

In 1960, O'Brien arrived in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Here, he reconnected with Margaret Phillips, an old friend, who introduced him to Merle Armitage, an author, critic and Art Director of Look magazine. Through the promotion of Armitage and Phillips, mural commissions began to come to O'Brien.[5]

O'Brien's final murals

Edward O'Brien's first commission in New Mexico was for Loretto Academy School for Girls in Santa Fe. "Our Lady of Light" was unveiled September 8, 1963. The work has since been twice moved and currently resides at Los Hermanos Penitentes in La Madera. Armitage wrote an article in the Santa Fe New Mexican celebrating the work. The next year, Armitage and Phillips published a book on O'Brien's life and work: Painter into Artist: The Progress of Edward O'Brien.[6]

O'Brien began his next work at St. Catherine's Indian School in Santa Fe in January 1965. It depicts ten important events in the history of the indigenous peoples of the Americas. He called it "Our Lady of Guadalupe's Love for the Indian Race." It was completed after its formal dedication on June 18, 1966. Though the school closed in 1998, the building where the mural is located is protected as an artistic treasure by the New Mexico government and a citizen's group.[7]

Edward O'Brien was next commissioned to paint a mural depicting stories of appearances of the Holy Mother at the Benedictine Our Lady of Guadalupe Abbey in Pecos, New Mexico.[8]

O'Brien's next three years were spent at St. Benedict's Abbey in Benet, Wisconsin. There, he diverged from the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe to make a mural in their Monastery Retreat Dining Room entitled "Christ in Man." While he worked, O'Brien lived among the Abbey's Brothers. It was finished in 1969.[9]

Edward O'Brien's next commission took him to the Catholic Parish of St. Pius V in Chicago, Illinois. Painted on a curved wall, this was to honor the people of Latin America and was entitled "The Mother of the Americas." This work was completed in 1972.[10]

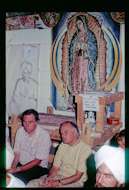

Upon his return to New Mexico, O'Brien met some young American Sikhs who wished to see his mural at St. Benedict's Abbey. They discussed with him the image of "Our Lady of Guadalupe" and how it compared with the feminine principle in Sikh Dharma. After many meetings, O'Brien agreed to create a mural for them and to move into the Sikh ashram in Espanola, New Mexico in the spring.[11]

According to members of the Espanola community, "his desire to learn about the Sikhs and their gurus had no end and his quest for this knowledge rapidly reshaped the meaning of his life."[12] O'Brien, who had spent his mornings reading Psalms, began instead to read from an anthology of Sikh sacred verse. In place of his rosary, he began to wear a coral mala and instead of the medals he had worn around his neck, he began to wear an Adi Shakti (Khanda (Sikh symbol)) pendant of the Sikh faith.[13]

Edward O'Brien was so keen to begin his work that when his move was delayed by two months, he began work on the centerpiece at his home. When he joined the ashram community, he never expected anything special for himself and continued his work with great determination and devotion. When his work drew the attention of Yogi Bhajan the head of the Western Sikh community, the master requested O'Brien also paint a mural for the Golden Temple in Amritsar, India.

In his mural, to either side of the central "Our Lady of Guadalupe," O'Brien depicted the elements, Sikh gurus, and historic episodes of the past and an imagined future. On May 1, 1975, a week after he had finished the work in the ashram, the devoted muralist died of a heart attack at the ashram.[14]

Funeral and remembrance

Edward O'Brien's remains were brought to St. Catherine's Indian School in Santa Fe for the funeral which was held in front of the mural he had painted there. The service was a blend of Christian ritual with, Indian and Spanish music, and Sikh elements. O'Brien's brother, Reverend Vincent M. O'Brien celebrated the Mass. In his eulogy, Yogi Bhajan said, "He will be known in the history of man from this time forth. Books will be written on his works. Pilgrimages will be made to see his murals and the power of his faith captured in paint."[15]

In memory of his passing, the Governor of New Mexico, Toney Anaya declared May 5, 1985 Edward O'Brien Day.[16]

References

- Peter E. Lopez (2013). Edward O'Brien Mural Artist 1910-1975. Santa Fe: Sunstone Press, pp. 13-15

- Lopez (2013). pp. 15-16

- Lopez (2013). pp. 17-19

- Lopez (2013). pp. 20-24

- Lopez (2013). pp. 24-25

- Lopez (2013). pp. 25-26

- [Lopez (2013). pp. 26-27; http://newmexicohistory.org/places/saint-catherines-industrial-indian-school]

- Lopez (2013). pp. 27-28

- Lopez (2013). pp. 28-29

- Lopes (2014). p. 29

- Lopez (2013). p. 30

- Wha Guru Singh Khalsa and Ramanand Singh (1975). "Ed O'Brien" Beads of Truth magazine. Fall 1975, Issue 28, p. 18.

- Khalsa and Singh (1975)

- Lopez (2013). pp. 30-31

- Lopez (2013). p. 31

- Lopez (2013). p. 32